Today, our perception of the muse is of a passive, powerless female model, often at the mercy of an influential and older male artist.

But, if we dig a little deeper into art history, could it be that this trope is a romanticised myth? Far from posing silently, have muses brought more to the role than external beauty? Did some even deliberately seek out the status of muse? By exploring the true stories of eight muses, told from their perspective, we might find that these real-life individuals have been just as important as those they have inspired. Such individuals are featured in my recent book Muse: Uncovering the Hidden Figures Behind Art History's Masterpieces, published by Simon & Schuster.

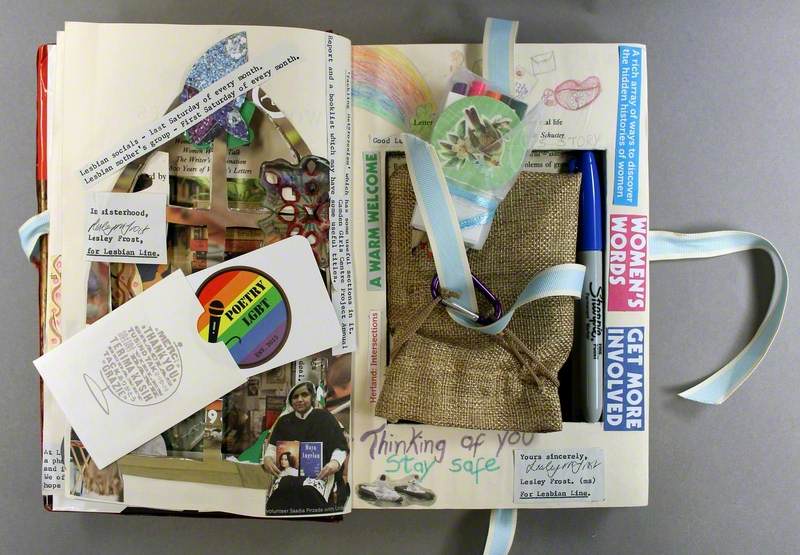

'Muse' by Ruth Millington

illustration by Dina Razin

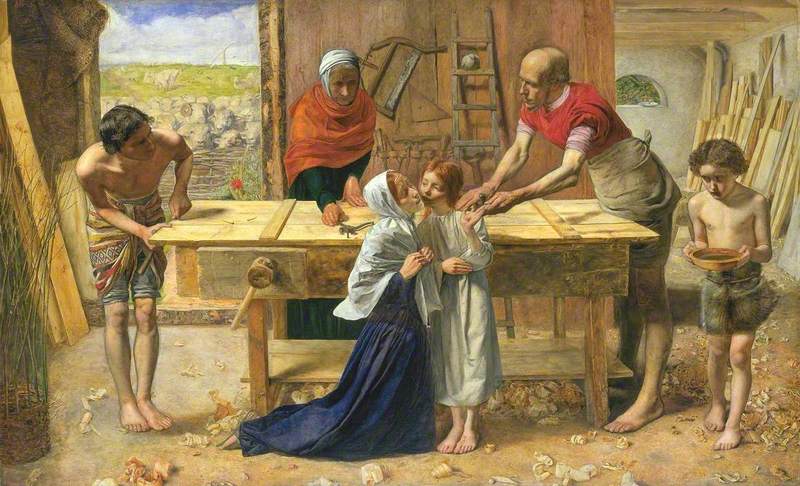

Elizabeth Siddal

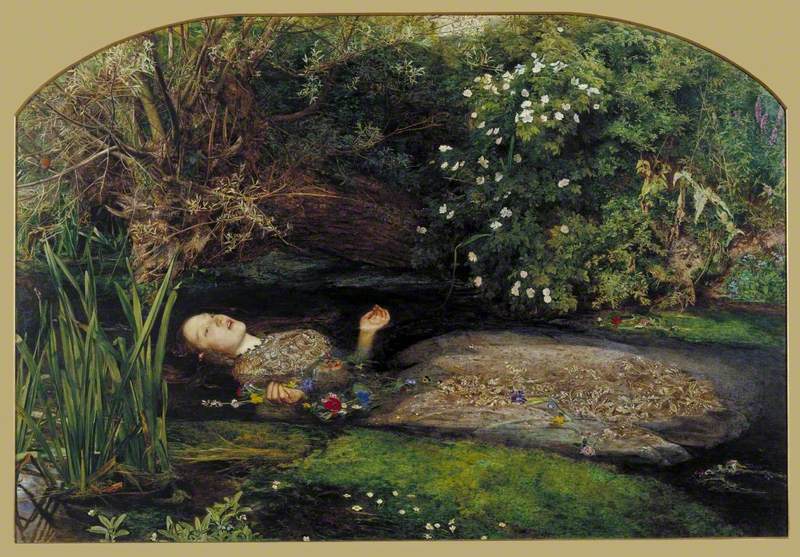

Elizabeth Siddal (1829–1862) is synonymous with Shakespeare's tragic heroine, as she modelled for John Everett Millais' Ophelia (1851–1852).

To represent the drowning character, Siddal posed, during winter, in a bathtub full of water for five hours. Becoming very ill with pneumonia, she almost died, and never fully recovered. Many accounts present Siddal as a doomed damsel, plucked from obscurity to become a Pre-Raphaelite muse. But, in truth, she wanted to partner with these painters as a means of infiltrating the male-dominated art world. In 1850s Britain, women were rarely allowed to exhibit publicly and barred from life drawing classes – unless they were the model!

Accepted into their ranks, Siddal began to show her work – she exhibited paintings and drawings alongside the male Pre-Raphaelites, including at a salon at Russell Place in London in 1857. She also had work sent to a group show in America and secured an exhibition for her paintings at a gallery on London's Charlotte Street. While Siddal is most famous for floating silently as Ophelia, a truer reflection of her is Dante Gabriel Rossetti's drawing, simply titled Elizabeth Siddal Seated at an Easel, Painting (c.1854–1855).

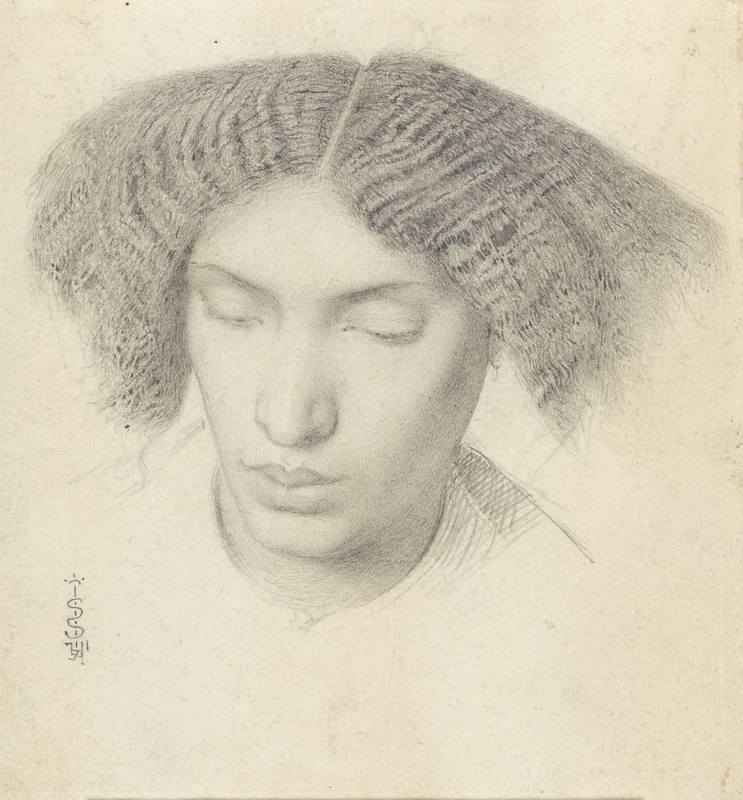

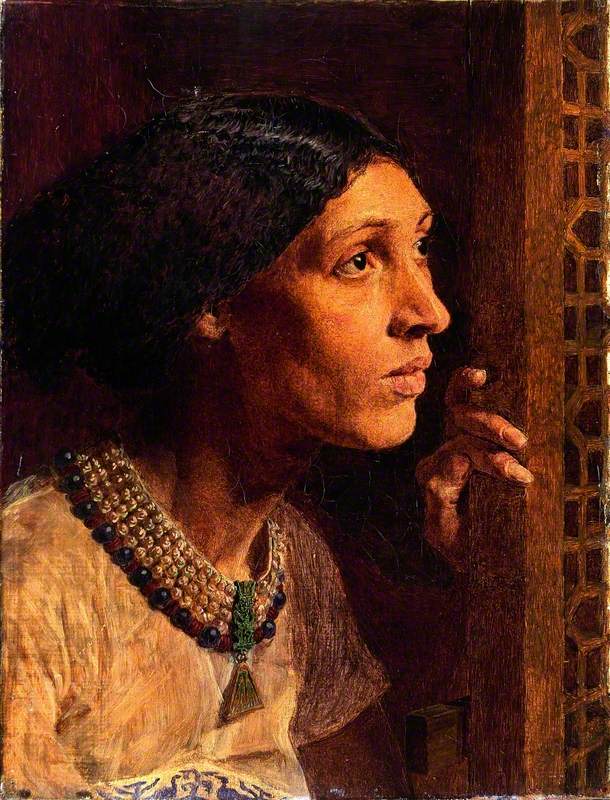

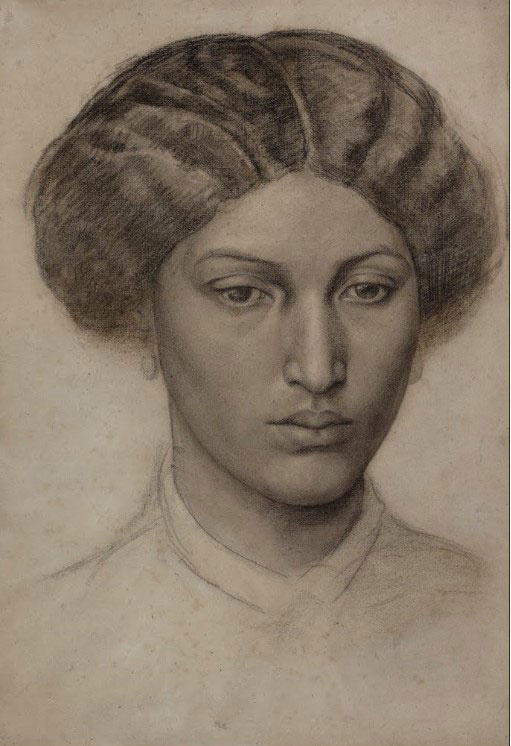

Fanny Eaton

Art history's obsession with Siddal, and 'white' beauty, has cast a shadow over other Pre-Raphaelite muses, including Fanny Eaton (1835–1924). The Jamaican-born muse came to London as a child, shortly after the abolition of slavery in British colonies.

The Mother of Moses

1860, oil on canvas by Simeon Solomon (1840–1905)

After modelling for Simeon Solomon's The Mother of Moses, which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1860, Eaton was soon in demand amongst the other Pre-Raphaelite painters.

Moreover, by modelling for the likes of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais and Joanna Mary Wells, she helped redefine Victorian standards of beauty, at a time when Black individuals were significantly underrepresented, and often negatively represented, in Western art.

Study of a Young Woman (Mrs Eaton)

c.1863–1865, black chalk & charcoal with stumping on paper by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

You can read more about Eaton in the story 'Fanny Eaton: Jamaican Pre-Raphaelite muse'.

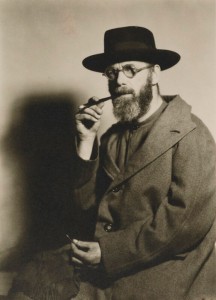

Emilie Flöge

Not all muses have been life models: Emilie Flöge (1874–1952), although pictured in several portraits by Gustav Klimt, brought her own talents as a fashion designer to what was a creative partnership between equals.

In 1904, Flöge opened the salon Schwestern Flöge with her two sisters, from where she designed and sold cutting-edge dresses, decorated in geometric shapes and swirling patterns.

Emilie Flöge

Her popular 'Reform dress' range was designed to liberate women's bodies from the corset, allowing them to participate fully in everyday life. It was in Flöge's store that Klimt met many of his models, portraying them in the dresses designed by his muse; in effect, Flöge was responsible for fashioning Klimt's trademark style on show in works such as Portrait of Hermine Gallia (1904).

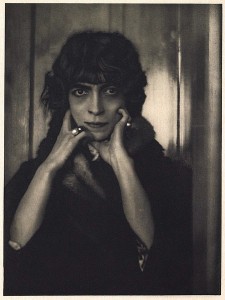

Dora Maar

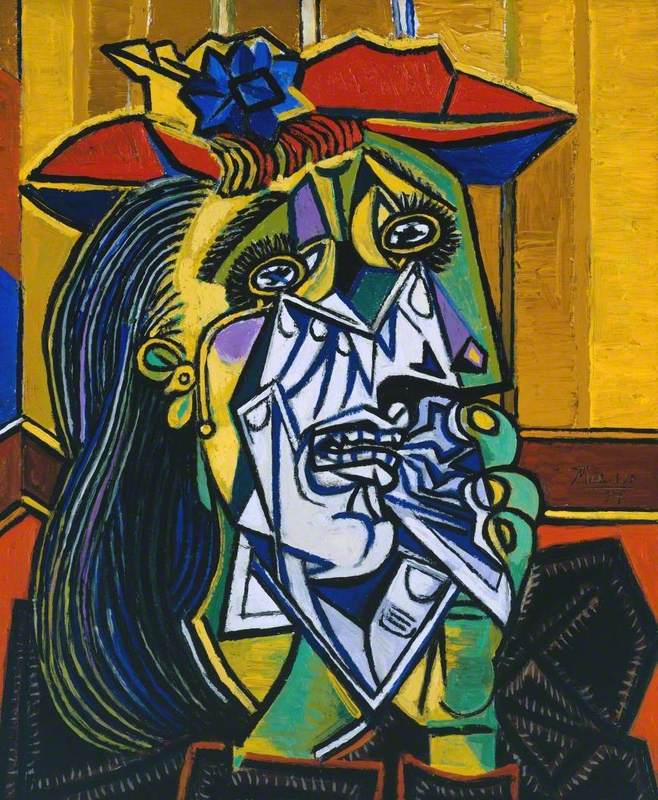

Many of the greatest muses have also been artists, bringing huge amounts of creativity to the role. In her darkroom, successful Surrealist photographer Dora Maar (1907–1997) taught Pablo Picasso complex photographic processes, such as cliché-verre, meaning 'glass picture', which involves drawing handmade negatives on glass. Under her direction, Picasso used this technique to create a series of startling, unposed portraits of her.

Outside of the studio, Maar also indoctrinated the painter in her ultra-Left-wing politics, which infused not only Picasso's portraits of her but also the epic anti-war mural, Guernica (1937).

In fact, it was Maar who found Picasso a site large enough for this huge protest painting — the former headquarters of her radical political group, Contre Attaque. Inside the space, Maar photographed Picasso making the mural and helped him with sections of painting it. Leaving his bright palette behind, he created Guernica in black and white, influenced by Maar's photography. There is even a darkroom spotlight in the picture, beneath which appears, for the first time, Picasso's famous Weeping Woman.

That same year, Picasso painted a stand-alone portrait of Maar as The Weeping Woman, crying glass tears. This portrait is often read – in patriarchal narratives that frame women as romantic partners – as an inflection of her troubled relationship, and the abusive way in which Picasso treated her. But, if you look closely, you can see black warplanes in her eyes, proving Maar's political convictions, which had a profound impact on Picasso.

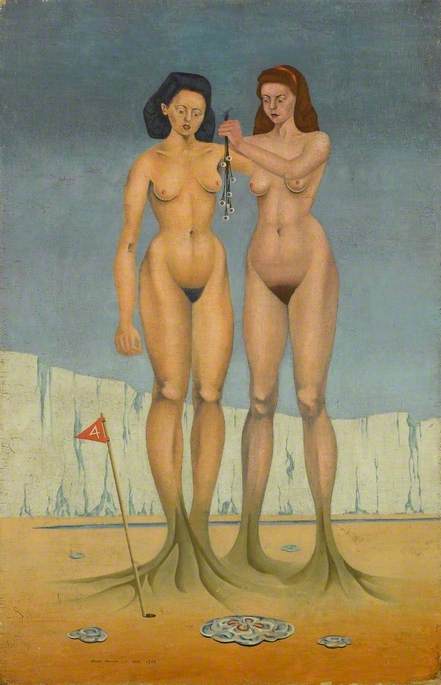

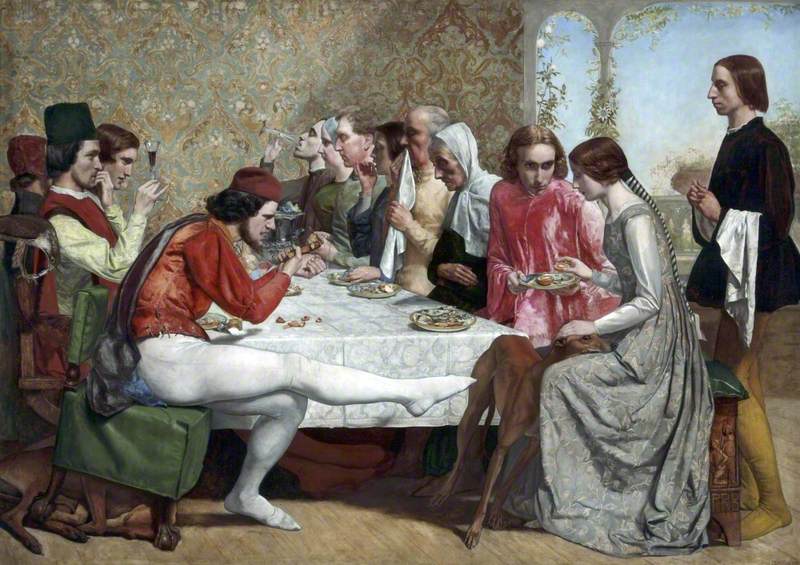

Paul Rosano

In 1970s New York, musician, artist and life model Paul Rosano was a significant muse of the feminist painter, Sylvia Sleigh (1916–2010), who became known for gender-swapping art historical masterpieces by Ingres, Titian and Velázquez. She painted male subjects, who were close friends and collaborators in this feminist project, as the subject of the female gaze. As she explained, 'I had noted from my childhood that there were always pictures of beautiful women but very few pictures of handsome men so I thought that it would be truly fair to paint handsome men for women'.

In 1975, Sleigh's painting Paul Rosano: Double Portrait (1974) was included in an exhibition at the Bronx Museum, which at the time was located in the district courthouse. Justice Owen McGivern launched a complaint: 'We are all in sympathy with the arts, but explicit male nudity in the corridor of a public courthouse is something else.' Asked about the reaction to her painting, Miss Sleigh said: 'I wonder if the judge would object to a female nude? I don't see why male genitals are more sacred than female.'

Lawrence Alloway

Sleigh also painted over 50 portraits of her husband, Lawrence Alloway (1926–1990), who is easily identified by his bright blonde hair and blue eyes. Sleigh portrayed him naked on many occasions, lying in bed, reclining on the sofa or positioned in gender-swapped masterpieces such as The Turkish Bath (1973).

Sylvia Sleigh's iconic 'The Turkish Bath' back on view this spring as part of 'Expanding Narratives' https://t.co/wE5ZxAasKU

— Smart Museum of Art (@SmartUChicago) March 24, 2018

Moreover, in The Bride (1949), Alloway appears as Sleigh's cross-dressing, Renaissance-style bride, toying with constructed gender roles. An influential art critic and curator, who worked for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City, Alloway posed for Sleigh in a true act of allyship with her feminist vision – that both male and female muses be seen on equal terms.

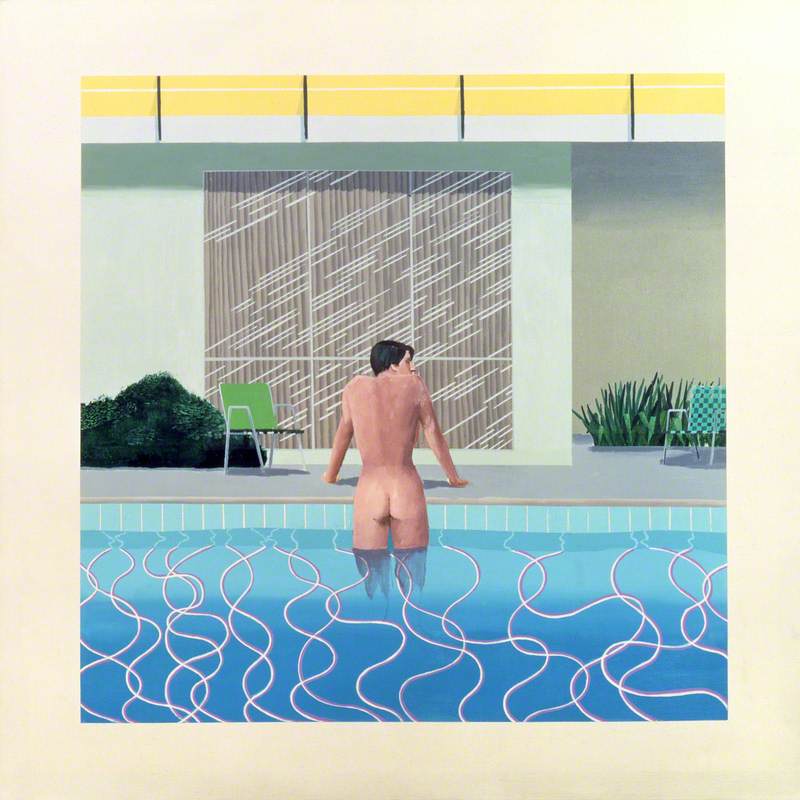

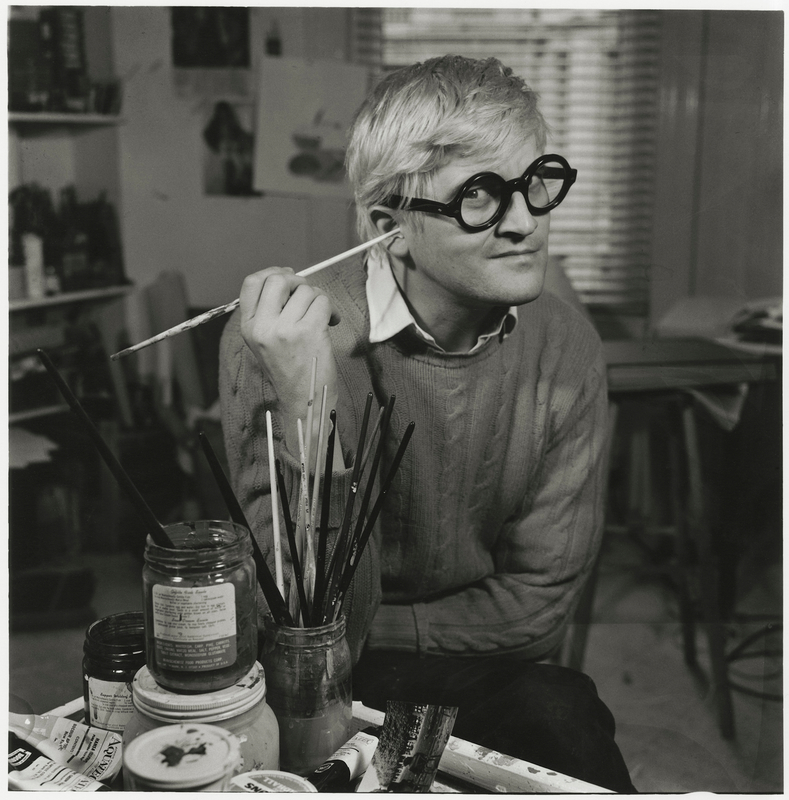

Peter Schlesinger

Like Sleigh, David Hockney (b.1937) collaborated with many naked male muses, although in his case adopting the male-on-male gaze to celebrate his sexuality on canvas. Among his most significant subjects was American photographer and artist, Peter Schlesinger (b.1948).

It was LA-based Schlesinger who invited Hockney into his world of swimming pools in back gardens, including his own family's. Hockney's muse provided him with career-changing subject matter – he subsequently reworked the tradition of bathers in art through a homoerotic lens.

It was Peter Getting out of Nick's Pool which won David Hockney the highly respected John Moores Painting Prize in 1967. This was the same year that homosexuality was partially decriminalised in the UK. Schlesinger acted as a bold icon for gay identity and culture in Hockney's paintings before pursuing his own career as an artist.

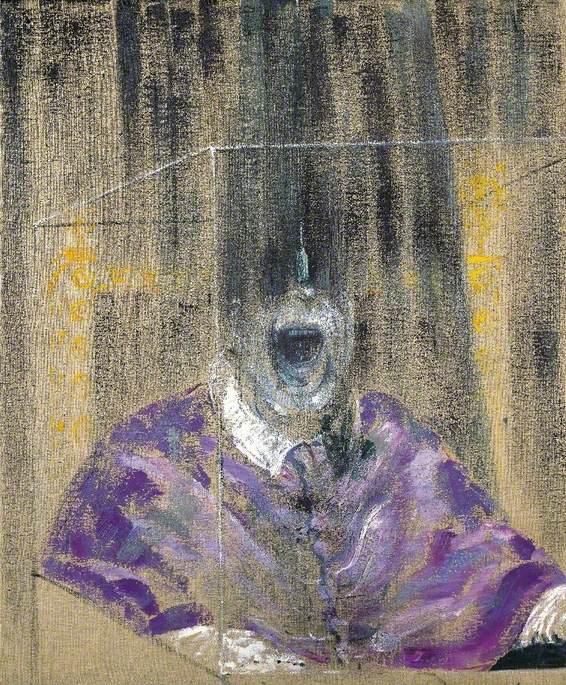

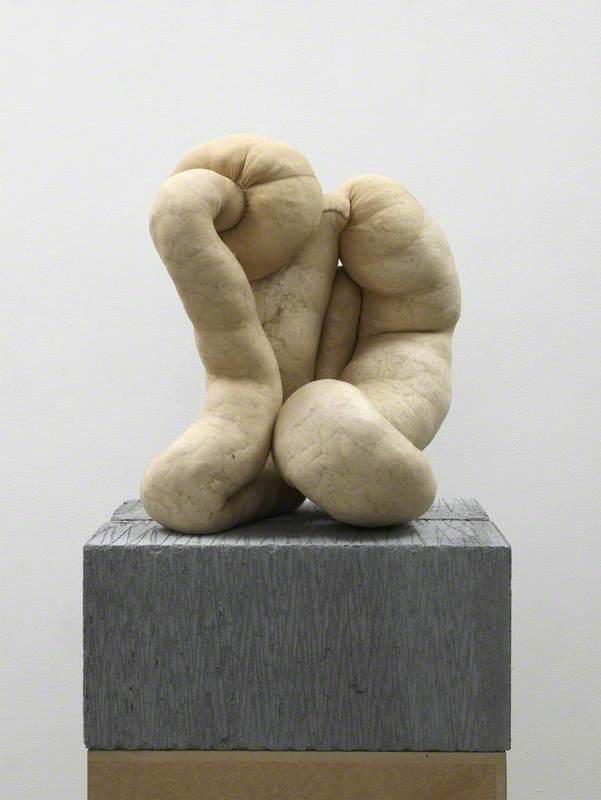

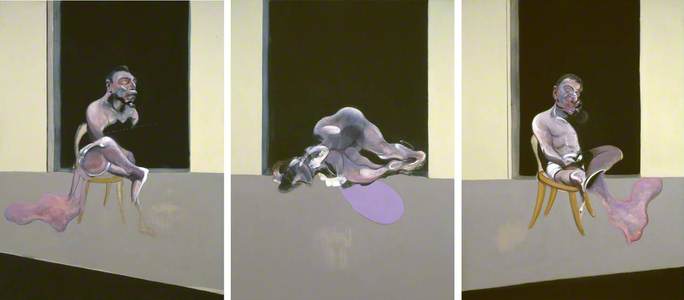

George Dyer

Male figures also dominate the nightmarish paintings of Francis Bacon (1909–1992), who depicted his romantic partners in raw and uncompromising terms. Among his most influential, and unlikely, muses was the well-built East End criminal, George Dyer (c.1933–1971), whom he met in Soho in 1963.

In over forty portraits, many of them triptychs, Dyer's contorted figure appears against a shadowy black background. However, none are as haunting as Triptych – August 1972 and the wider series of four 'Black Triptychs' painted by Bacon in the early 1970s. Bacon created each of these works in memory of Dyer, who had committed suicide on the night before his partner's first major solo show.

In 1985 Bacon told The Times that his series of four 'Black Triptychs' are 'of somebody – a great friend of mine. When I had a show in Paris in '72 he committed suicide. He was found in the lavatory like that and he was sick into the basin. And I suppose in so far as my pictures are ever any kind of illustration this comes as close as any to a kind of narrative'.

While we often think of the muse possessed by, and serving, an artist, it's clear that this is far from the truth. Instead, muses have often had great power over the artists they have inspired, bringing emotional support, intellectual energy, career-changing creativity and practical help to the role. In both life and in death, muses have left an indelible mark upon the artists who immortalised them.

Moreover, muses have been far more diverse than traditional accounts have allowed for – at times, their inclusion in a portrait has carried bold, and even political, statements. It couldn't be clearer: the muse is an active agent of art history, without whom we wouldn't have many of the world's most famous masterpieces.

Ruth Millington, art historian and author of Muse: Uncovering the Hidden Figures Behind Art History's Masterpieces, published by Penguin in the UK and Pegasus in the US