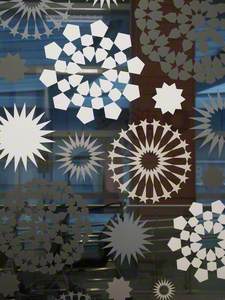

Mathematics is written into, through and within the work of British artist Zarah Hussain (b.1980) and it is a sacred geometry. In Hussain's practice, intricate combinations of shape, colour and line produce complex spatial and optical forms.

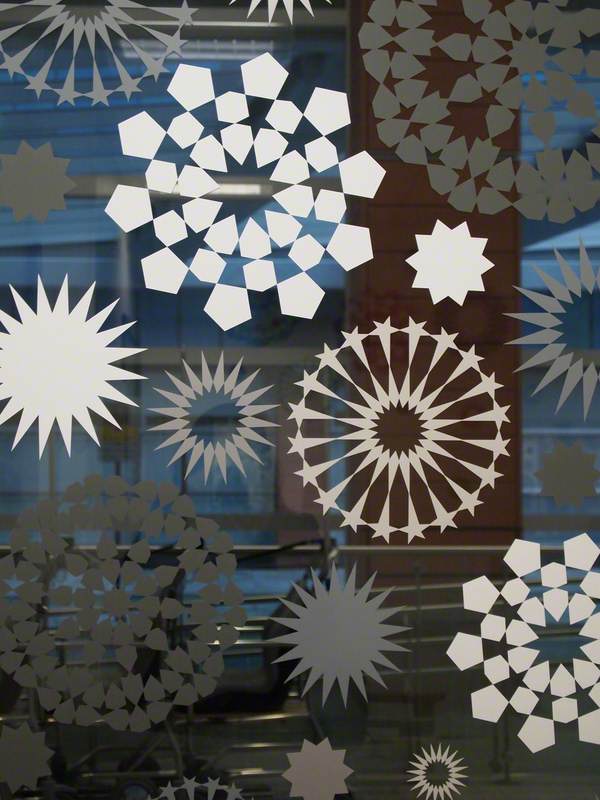

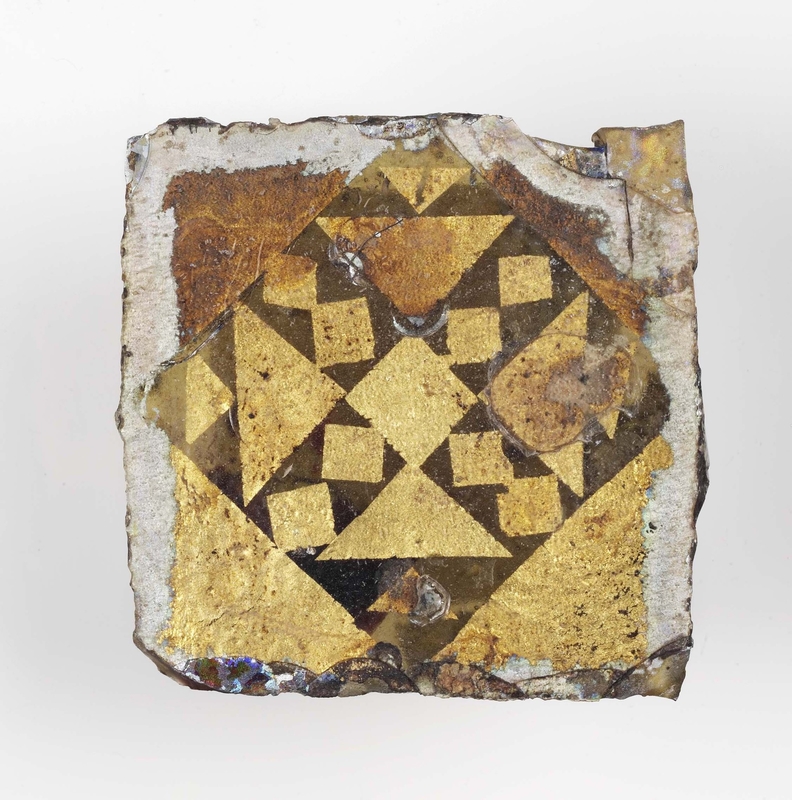

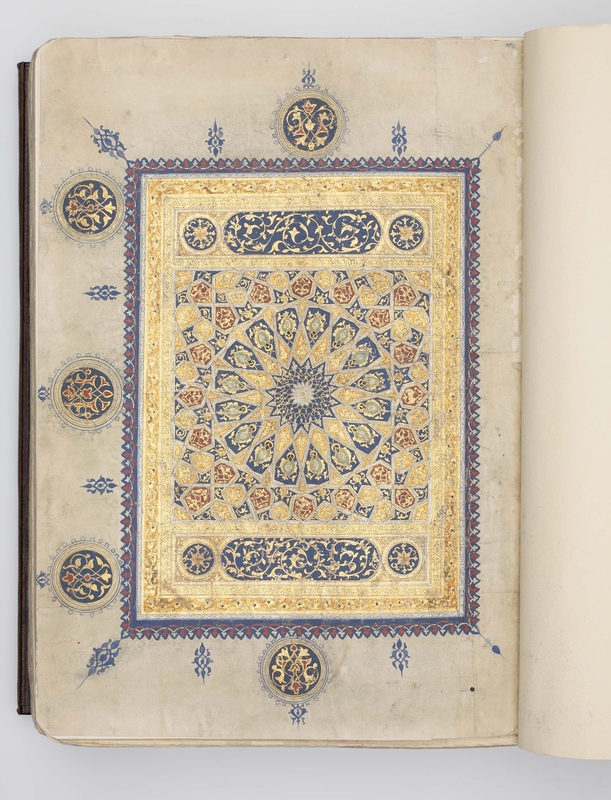

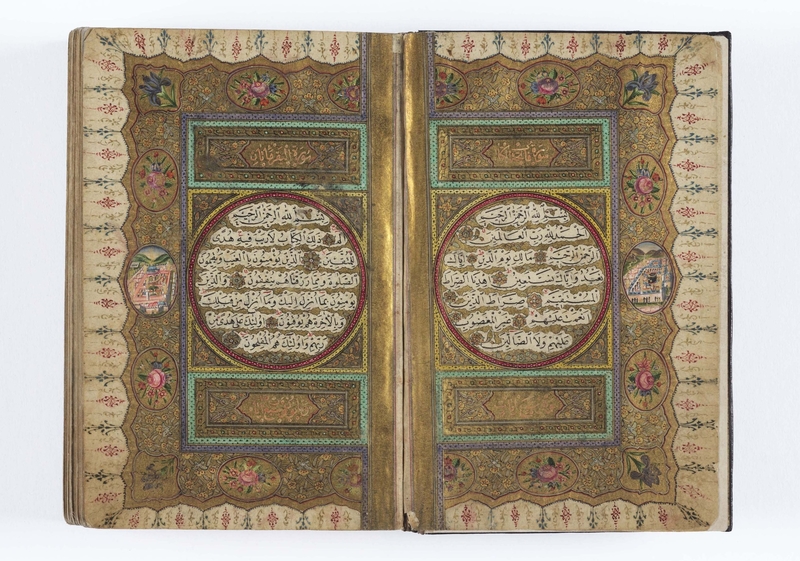

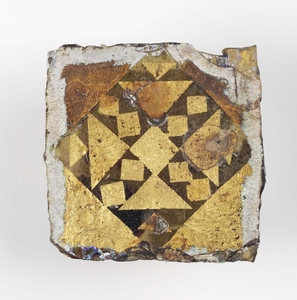

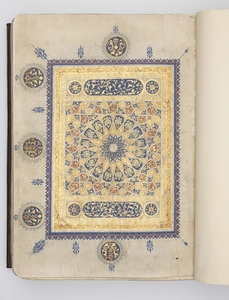

The resultant forms draw inspiration from the patterns that have long been recognised in the art and material culture found in the vast geography of the Islamic world. Examples of these aesthetic traditions are embedded in a wide array of art and objects: from cartographic maps, tiles and illuminated frontispieces to architectural surfaces and textiles.

Hussain draws on these traditional legacies and re-interprets them, working across digital media, painting and sculpture.

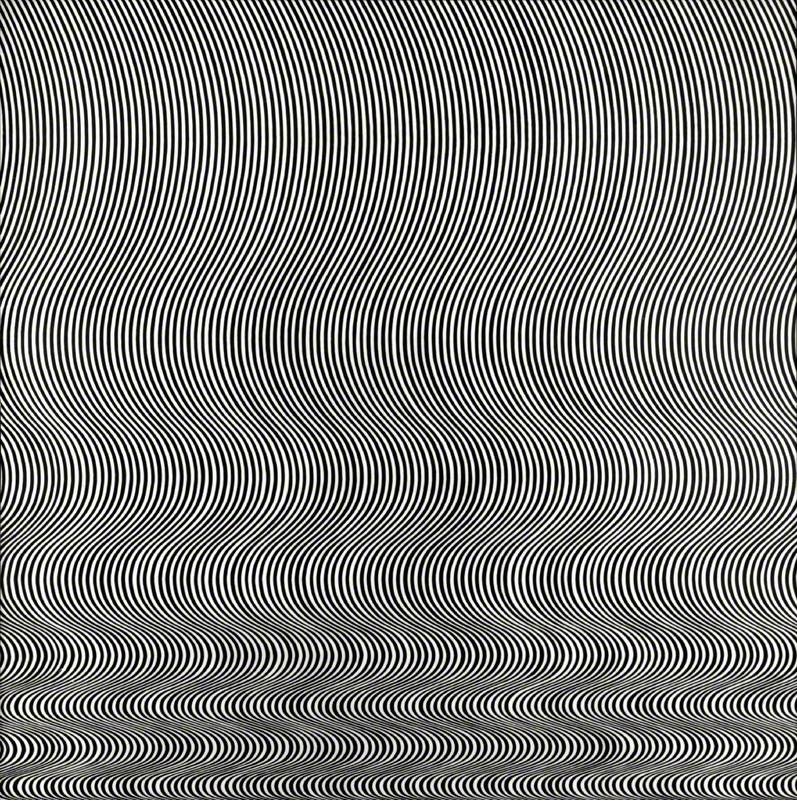

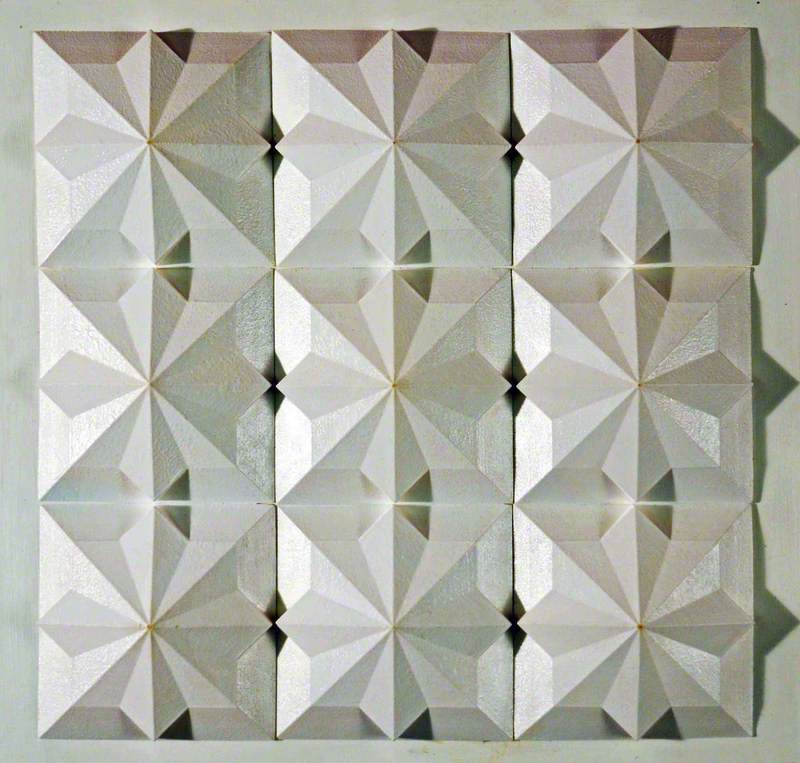

At the beginning of her artistic career, Hussain made large abstract canvases inspired by the work of Bridget Riley and the Op art movement that developed in the 1960s, but found the work, as she explained in a 2004 interview for a-n Magazine, to be 'cold' and unmoving.

School in the north-west in the 1980s had taught the European canon. Hussain recalls an exchange with her art teacher: 'We do Matisse, we do Picasso, we did Frida Kahlo one time, is there no art from China, is there no art from Africa, is there no art from where my family is from?' (Mirpur, Kashmir.)

Her teacher brought in a selection of books on Islamic art, and one volume on Moroccan architecture presented a welcome challenge, being formed of extraordinarily beautiful patterns built out of complex mathematical formulae and hard to decipher. 'I just fell in love,' Hussain tells me.

Hussain earned an MA from the Prince's Foundation School of Traditional Arts in London, working within the Visual Islamic and Traditional Art department. She was taught by Paul Marchant and Keith Critchlow, who were skilled in geometric compositions, and she discovered 'the inherent beauty of number and how this relates to the natural world and the order that pervades the universe'.

Hussain's practice does not simply produce abstract art, devoid of figuration – as the work of Islam has so often been characterised by European scholars – though her practice is profoundly abstract.

Her art is the product of creative choices, of visual expression, rooted in the rich history of pattern-making as a channel for meaning – or to collapse the idea further, as Islamic art historian Oleg Grabar has suggested, the pattern is the meaning. In this interpretation, pattern is distanced from the European analysis of it being purely decorative and instead provides an immediacy of experience for the viewer.

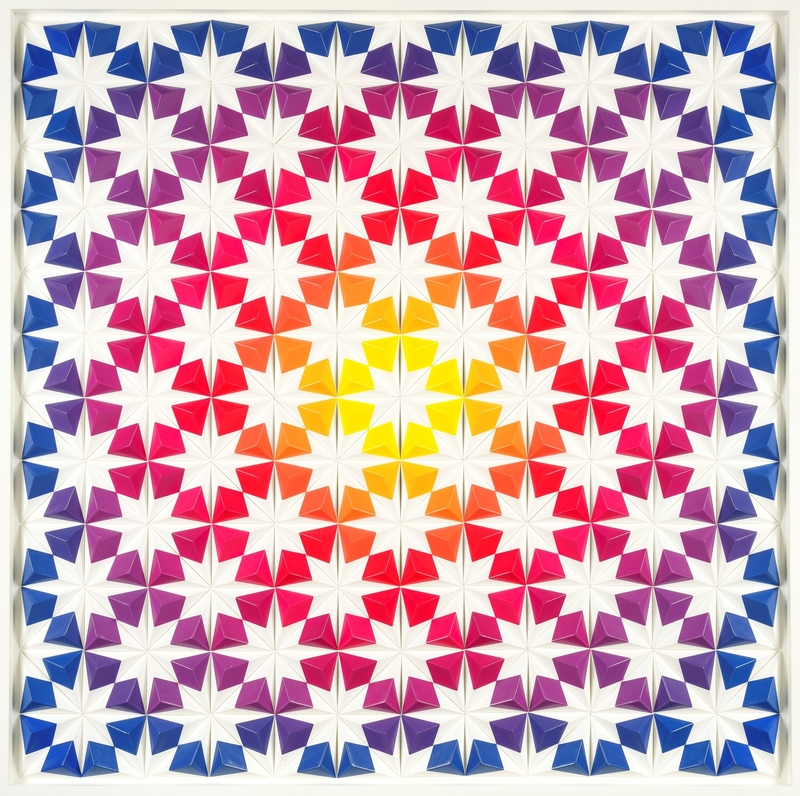

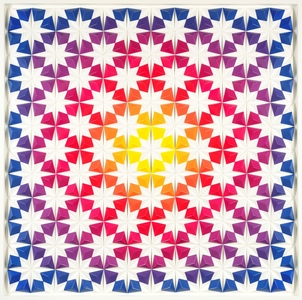

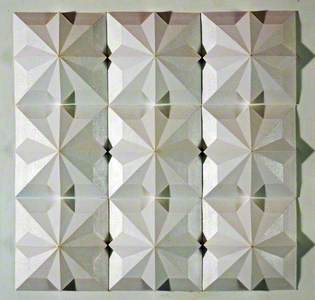

ROOT 2: YELLOW, BLUE (2021), for example, is a three-dimensional work which took Hussain two years to resolve. Drawing on Islamic tradition, the resultant work could inherently never achieve perfection as that is reserved for Allah or God alone. But grappling with the many possibilities of geometry, the infinite combinations of colour, the (unobtainable) quest for mastery in her chosen art form, is a perpetual and humbling process.

As a wall-based work, ROOT 2: YELLOW, BLUE needed to be lightweight yet robust and, as Hussain tells me, several prototypes were made in order to strike the balance between practicality and form. The achieved movement between complex beauty and simplicity, the tangible world and the unknowable, is crucial to Hussain's practice which occupies the space between these two positions.

Central to the geometry of ROOT 2: YELLOW, BLUE is the square, with the title of the work referring to the length of its diagonal. To represent the square is to call to mind its spiritual and art-historical significance.

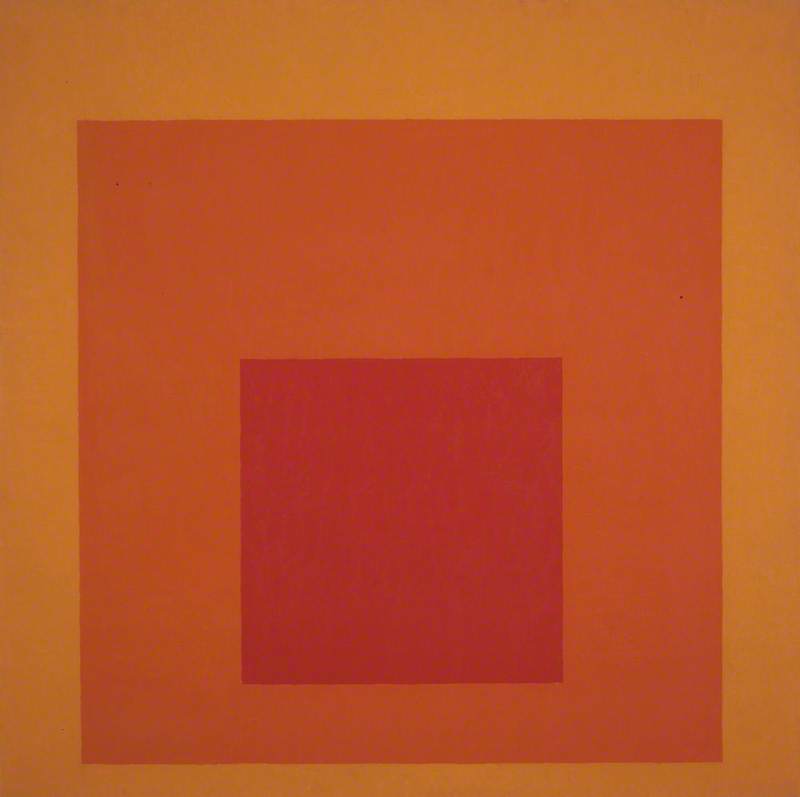

Hussain's practice draws on a wide range of influences and art-historical references, including Josef Albers (1888–1976). His series Homage to the Square, begun in 1949, presents varying colour combinations set over an unchanging pattern of squares to produce alterations of perception. Hussain cites a lecture that Albers gave on abstract art in 1935 to also highlight how abstract art enables a number of different interpretations:

'Take for instance the word red. Even when you explain this red more precisely through other words, "dark, light, deep, flat, active, substantial, loose, dense, transparent, opaque" – still we will have different reds in our minds.'

Hussain's interest in Albers and her centring of the square in ROOT 2 and other works is significant within the spiritual universe of Islam, as it invokes its most holy shrine: the Kaaba in Mecca. Muslims must come to the nothingness at the centre of the Kaaba without prejudice and with an open heart. Only then can they come to the divine.

Hussain invites us to lose ourselves through the experience of pattern, through the generosity of the abstract – just as she loses herself in the making of the work.

As Islamic scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr outlined in his introduction to Keith Critchlow's 1999 book Islamic Patterns, within Islam, 'Abrahamic Pythagoreanism' describes a way of seeing numbers and figures as keys to the structure of the cosmos. This is visible in the organic, harmonious designs of Halima Cassell's (b.1975) sculptures that spring from vegetal forms found in nature.

Wu-Li (Patterns of Organic Energy) (2012), for example, represents an unfurling fern frond, revealing the underlying fractal structure of nature, while Concentric Flower (2003) is kaleidoscopic in shape and form.

'Aniconic' art, in which the spiritual world is reflected in the physical world, not through iconic forms (such as Christ) but through geometry and rhythm, is closely linked to Islamic art. The intentional absence of religious figuration points to a powerful, marked absence, namely Allah or God. Where physics and cosmology have revealed the essential mathematical patterns and geometry occurring in the natural world and aims to look back in time to trace the origins of creation, Islam instead seeks to look inward.

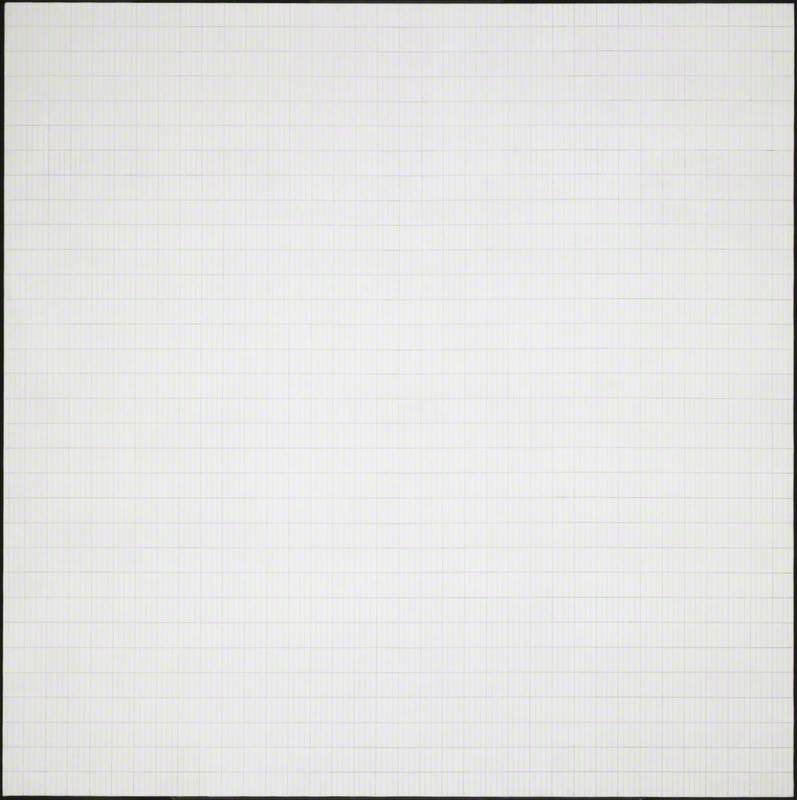

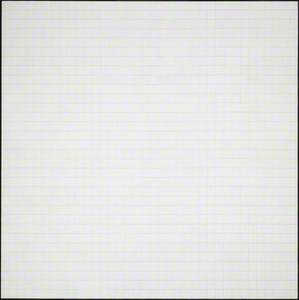

In a similar vein, Agnes Martin's (1912–2004) paintings reject Abstract Expressionism for a more spiritual, constrained format: six-by-six foot canvases that the artist meticulously covered with grids and a layer of gesso. The large scale of these works enables a meeting between the spiritual and physical world, as do Hussain's.

For Martin, painting was 'a world without objects, without interruption… or obstacle. It is to accept the necessity of… going into a field of vision as you would cross an empty beach to look at the ocean.' It is perhaps significant that Martin's work reproduces the square and that Hussain cites Martin as an inspiration.

Hussain quotes the French philosopher, scientist and priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin who, interestingly, combined these disparate disciplines as Hussain does: 'We are not human beings having a spiritual experience. We are spiritual beings having a human experience.' Perhaps Hussain's role, then, is to navigate the interface between the two. As she stated in a-n magazine, ‘The purpose of my artwork is to help humans to contemplate the divine.'

Hattie Spires, writer and curator

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation

Further reading

Sussan Babaie and Roxane Zand, Geometry and Art: In the Modern Middle East, Skira, 2009

Carol Bier, 'Art and Mithal: Reading Geometry as Visual Commentary', in Iranian Studies 41, no. 4, 2008

Keith Critchlow, Islamic Patterns: an analytical and cosmological approach, Thames and Hudson, 1999

Oleg Grabar, The Mediation of Ornament, Princeton University Press, 1992

Robert Hillenbrand, Islamic Art and Architecture, Thames and Hudson, 1999

Zarah Hussain, 'Unity in Pattern: Zarah Hussain', in a-n Magazine, October 2004

Mahmood Jamal (ed.), Islamic Mystical Poetry: Sufi Verse from the Mystics to Rumi, Penguin Classics, 2009

Nasser D. Khalili, The Timeline History of Islamic Art and Architecture, Worth Press, 2005

Laura U. Marks, Enfoldment and Infinity: An Islamic Geneology of New Media Art, MIT Press, 2010

Ali Wijdan, Modern Islamic Art: development and continuity, University of Florida, 1997

Ann Wilson, 'Linear Webs', in Art & Artists 1, October 1966