In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

Since 2011, the artist Issam Kourbaj has been dedicated to raising awareness about conflict in Syria, his native country.

Working across many mediums, including painting, works on paper, sculpture, film and performance, he regularly finds inspiration from both the creative sciences and humanities, and his collaborations with museums and public collections, which could be described as 'interventions', involve the reconsideration of particular artefacts. By responding creatively and conceptually to such historic objects, he prompts new discussions about the state of the world and our perspectives on material culture.

Intimate Distances

2010, optical image made by a constructed camera obscura by Issam Kourbaj (b.1963)

Born in Suweida, in southwestern Syria, Kourbaj trained at the Institute of Fine Arts in Damascus, the Repin Institute of Fine Arts and Architecture in Saint Petersburg (when it was still called Leningrad and in the Soviet Union) and at the Wimbledon School of Art in London. Since 1990, he has lived and worked in Cambridge where he is artist-in-residence at Christ's College.

I spoke to the artist about the trajectory of his multidisciplinary practice and about what he has planned next.

Lydia Figes, Art UK: Your work is a personal reflection on your Syrian cultural identity. But it didn't initially occur to you to centre your practice on Syria when the conflict began in 2011. How did this subject eventually enter your practice?

Issam Kourbaj: My interest in exploring issues of conflicts and migration started when I visited Havana, Cuba in 1995. I saw that Cubans were making boats out of their own furniture, in an attempt to migrate to Miami. In response to this, when back in Cambridge, I began making artwork out of furniture. At the time, my studio was located behind the ADC Theatre, so I would find disused theatre sets and props that I could incorporate into my artwork.

Chorus

2003, mixed media installation by Issam Kourbaj (b.1963)

When the crisis started in Syria in 2011, it took a couple of years to form an artistic response. In fact, I hadn't been back to Syria since 2007, but it is very painful to see the erasure of my childhood places, so I felt empty and unequipped to deal with the magnitude of the crisis. Slowly, I began making work in response, but I still didn't feel comfortable exhibiting it at that time.

Only in 2013, when I found a large exhibition space belonging to Christ's College, Cambridge – an empty furniture shop with huge glass windows – did I show work that engaged directly with the conflict. At that time, I had been experimenting with light and optics, so the light-filled space also triggered the idea of working with X-ray plates: a loaded medium with which I could respond creatively to the issue of war.

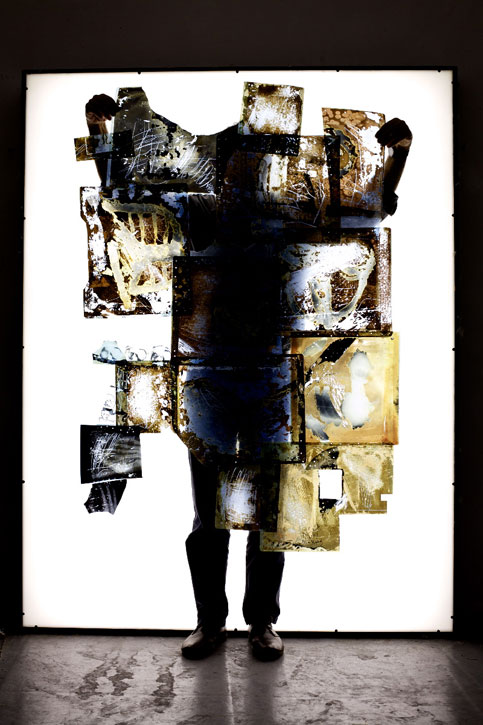

Excavating the present

2013, X-Ray plates and photograms by Issam Kourbaj (b.1963)

Under the title 'Excavating the Present', my exhibition contained artworks that used layered X-ray images of different body parts (which I would call 'skins') alongside images of the land from the perspective of the sky. The show opened on 21st March 2013 (Mother's Day in Syria) and referenced the disturbing fact that some Syrian mothers had been forced to gather the body parts of their children in order to bury them. For me, using X-ray images – themselves photograms from which I created photograms again – evoked both the idea of layers of excavation and the reality of traumatised bodies.

Lydia: Your work Dark Water, Burning World (2016), which can now be found in the Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic world in the British Museum, also responds directly to the humanitarian and refugee crisis. How did the symbol of the boat become a particularly important metaphor?

Issam: I didn't want to bombard my audience with images of war: there were enough of these in the media, and I think they can have the effect of flattening the conflict and desensitising people to it. Instead, I was constantly searching for another language to articulate war and, around the same time, many museums started inviting me to respond to their collections, such as the British Museum, Brooklyn Museum and the Penn Museum.

Dark Water, Burning World

2016, discarded bicycle steel mudguards, matches and resin by Issam Kourbaj (b.1963)

In April 2016, I found Syrian artefacts in the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum that sparked my imagination: miniature lead boats carrying three goddesses from the fourth century BC. It struck me as significant that, in ancient times, Syria sent goddesses to the Mediterranean, but in the twenty-first century, the country was sending people to the sea, not as revered deities but desperate refugees.

And this is how the symbol of the boat inspired me. I started experimenting with lead – a heavy and dangerous material to work with – because of the contradictory fact that the original artefacts were made from lead and would therefore immediately sink. But after my first few attempts, I abandoned the idea of using lead and replaced it with discarded bicycle mudguards, repurposed for my artworks. To reflect on the trauma inflicted on so many Syrians, I placed burnt matchsticks inside the boats, as if they were tiny refugees huddled together in these flimsy miniature boats.

When this work was chosen as 'Object 101' on the tenth anniversary of BBC Radio 4's A History of the World in 100 Objects, Neil MacGregor, former Director of the British Museum, described the work: '[it] stands for all migrants anywhere, driven by fear, guided by hope'.

For this object to be selected as one that would best encapsulate the preceding decade was not only a huge honour but also an enormous responsibility – it becomes a sort of historic declamation – as well as a heart-breaking truth of our modern age.

Lydia: Your work often seems to start with the material. In other words, you don't force a preconceived idea or concept onto the material, but rather the other way around. Would you say that's true?

Issam: Working with found objects is something I have been developing since I first arrived in Cambridge. There are many found objects in my studio. I am always collecting discarded objects: I like to give them new life. And often it is only by having a conversation with the object that I start developing the concept. I strive for the material, the concept and the context to work together, so that the work doesn't become merely decorative.

Scaling the dark: seeds, sands, moons

2021, mixed media installation by Issam Kourbaj (b.1963)

In 2021, I was invited by the curator Sarah Johnson to respond to the collection of the Dutch National Museum of World Cultures. An unassuming clay bowl in the collection of the museum plate from Aleppo with a humble drawing depicting the life cycle of a plant (seeds-flower-fruit-seeds) became the starting point for the whole intervention, which was called 'Fleeing the Dark' and was displayed at the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam.

Schaal, Aleppo

On entering the museum, visitors were greeted by my work Scaling the Dark: Seeds, Sands, Moons (2021), encompassing a specific number of various-sized boats, which acted as a calendar counting the months, weeks and days since the Syrian uprising in 2011. The smallest of these boats were made from tin cans, themselves invented to preserve food in wartime, and were carrying charred seeds, in response to the destroyed Seed Bank in Aleppo, and to the crops that were burnt as a result of war, devastating farmers and starving the innocent.

Scaling the dark: seeds, sands, moons

2021, mixed media installation by Issam Kourbaj (b.1963)

Lydia: You studied architecture in St Petersburg (Leningrad) from 1985 until 1990, before studying theatre design in London. Do you feel that these disciplines have always remained central to your practice?

Issam: I think I always knew that I wasn't going to be an architect or theatre designer, but there is no form of art outside of my interest or that does not inform my work: in fact, I strive to bring these disciplines to my practice, as well as others (I studied painting in Damascus, for example). But forming a visual voice cannot be achieved through training alone – you need practice, risk and to push boundaries. I have found that this is the most fertile ground for finding my own unique voice.

Currently, I am exploring performance art, photography and the power of words, and I am always eager to collaborate with mathematicians, archaeologists, engineers, astronomers, composers, dancers and theatre practitioners, which is a huge advantage of living in Cambridge.

Another Day Lost

2015, medicine packaging, discarded books and used matches by Issam Kourbaj (b.1963)

Lydia: You've lived in Cambridge since 1990. How has living in the UK and Europe more broadly, helped you to understand your own culture from an outside perspective?

Issam: It's a great privilege to live away from your native country – it's where you start seeing yourself and your culture more clearly. And seeing oneself from a distance means that one must construct the 'self' out of many different pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. I am from the volcanic mountains in the southern part of Syria and even the journey from my hometown of Suweida to Damascus is a huge contrast in terms of geology, culture, and architecture. After studying in Damascus, I lived in Baku, Azerbaijan, before moving to St Petersburg (Leningrad) when it was still part of the Soviet Union under Gorbachev.

Eventually I moved to the UK and my first impressions of Cambridge were the scale of the city and its well-preserved architecture. It resembled a theatre set: everything is very clean, and the people are so proper – it was a shock at first. Then, in 1990, I did not speak a word of English and my first two languages – Arabic and Russian – use totally different alphabets, but I managed to find common ground in all sorts of unexpected places. I have since met a great collection of people who have made this place welcoming, even though the concept of home has become an elusive and complicated one.

Lydia: One of your early paintings that is on Art UK is Symphony of St Petersburg (1990) in Christ's College, University of Cambridge.

Issam: This was the last painting I created in Russia. I had to carry this painting myself on the train from Russia to Poland, to East Germany, to West Germany, to Holland and finally to the UK. At every border, they asked what I was carrying; they thought I was mad to be carrying such a large painting.

The idea behind this work came from a particular moment, at the end of winter and beginning of spring, when the snow starts to melt, and you notice the first signs of life. I imagined the tiny sound of a tender bud breaking the ice, announcing the arrival of spring, while the sound of feet crunching on the snow has another quality.

From these sounds, the idea of a symphony came to me. I was interested in the idea of growth, the changing of seasons and the changing of time. Just as my more recent work uses seeds as a metaphor for hope, this painting reflected a time in Russia under Gorbachev, when an optimistic feeling filled the air. It was very different to Russia now: things felt more progressive and more hopeful.

Lydia: What do you have planned next?

Issam: Last year, to mark the tenth anniversary of the Syrian uprising in March 2021, which was during lockdown, I livestreamed a drawing and sound performance called Imploded, Burned, Turned to Ash (made with the composer Richard Causton and the soprano Jessica Summers and in collaboration with Kettle's Yard, The Heong Gallery and The Fitzwilliam Museum).

The video of this performance will be screened again for the upcoming Refugee Week (20th–26th June 2022) in multiple locations, including both altars of St James's Church, Piccadilly, London, and Great St Mary's Church in Cambridge. The ash (produced by my original performance) will be installed in a glass jar next to the screen at these locations. I am also planning to show the video in more locations worldwide (for which I welcome any ideas or invitations) to reflect the diaspora of Syrian refugees after more than a decade of conflict in our homeland.

This ambitious idea would not only mark the ongoing Syrian conflict, but also cast light on war's terrible continuity (even when it is no longer mentioned in the media) by reflecting the destruction of all cities and livelihoods, which we see repeated time and again, as is now tragically happening in Ukraine and throughout human history.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

'Imploded, Burned Turned to Ash: Richard Causton and Issam Kourbaj in conversation' will take place at the Royal Drawing School from 7pm on 22nd June 2022, and a screening of the same performance 'Imploded, Burned, Turned to Ash' will be shown at the V&A from 20th to 26th June to mark the tenth anniversary of the Syrian uprising.