The practice of drawing is, in a sense, the foundation upon which all other art forms are built. An artist requires nothing but a pencil and a sheet of paper to begin practising their hand, making it a particularly accessible medium.

Drawing is often an essential means of experimenting with new ideas or of capturing little moments of life that can inspire later, more finished artworks. It also forms a key part of artistic education. The potential for what an artist can create with the simplest of mediums is remarkable.

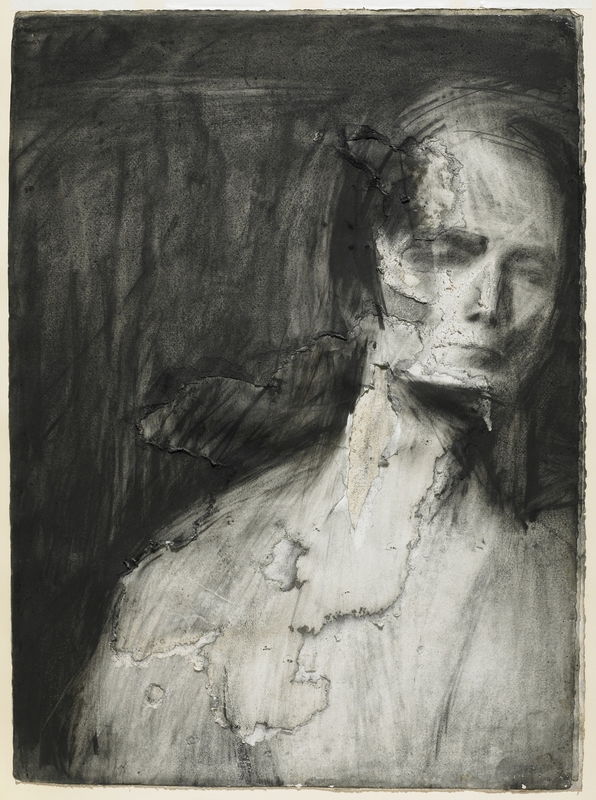

Drawings can become masterpieces in their own right, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti's mesmerizing La Donna della Fiamma.

Art historians often separate drawings into two general categories: those intended as a preliminary sketch, in which an artist is drawing a particular subject with the view of working these ideas into a finished artwork at a later date, and those that are meant as an independent finished work.

However, there is a third category of drawing which falls somewhere between those mentioned above. This category is 'study' or 'master copy' drawings, which are created when artists carefully observe and copy works deemed to be masterpieces.

It is important to note that this manner of creating 'studies' or 'copies' does not mean that an artist is trying to steal another person's work. Instead of plagiarising, these drawings clearly credit the original works, which were usually very well known. The practice of copying Old Masters is a well-understood and longstanding part of Western artistic education. In essence, it is the way one artist tries to gain insight into another's secrets.

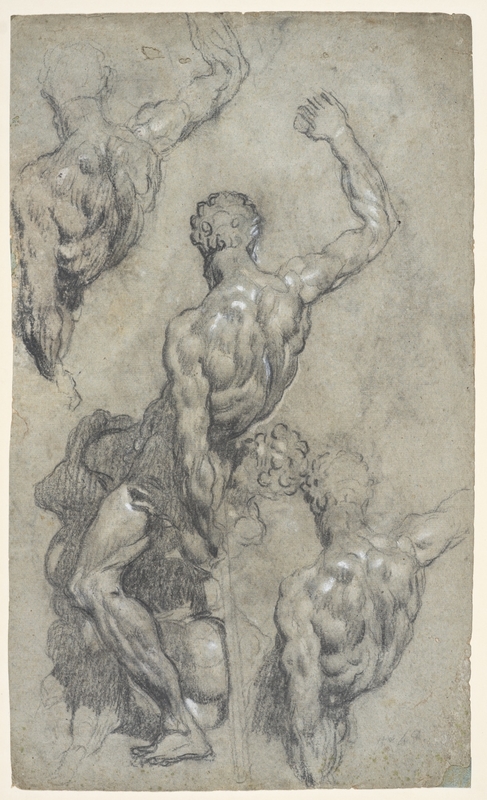

For example, the great Italian master Tintoretto made a careful study after Michelangelo's Samson and the Philistines.

Studies after Michelangelo's 'Samson and the Philistines'

c.1545–c.1555

Jacopo Tintoretto (c.1518–1594)

Michelangelo's work is now lost, but it was obviously significant enough in the sixteenth century for Tintoretto to take it as a muse. This points to another reason master copies can be so valuable to art historians: they can provide records of other works that are now lost or damaged, like this one.

Another example is the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens' drawing God the Father Supported by Angels, which is a direct study of a work by the Italian Mannerist painter Il Pordenone.

God the Father Supported by Angels

(after Pordenone) 1600–1603

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

Rubens was a particularly big believer in the benefits of studying the masters. He saw it as a non-negotiable part of any artist's training, just as it had been during the Renaissance. Before the founding of most modern museums in the nineteenth century, artists would usually study these works in churches, which was the main venue for their commission and display.

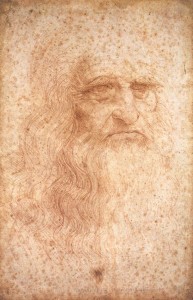

One of the most extraordinary examples of a master copy is a drawing by the French painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. He studied the portrait La Belle Ferronnière, painted by Leonardo da Vinci.

'La Belle Ferronnière'

(copy of a painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci) c.1802–1806

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867)

In trying to prove himself as the greatest artist of his generation, it is no surprise that Ingres would choose to copy the work of a man who is considered one of the greatest masters of all time.

When Ingres made this drawing, La Belle Ferronniere was one of the most famous Leonardo da Vinci paintings in the world. As the work of one of the greatest Renaissance masters, it would have been regularly copied by aspiring artists.

The work was part of the French royal collection and became available to the public in the Louvre Museum, which opened in 1793. This is where Ingres would have seen and copied it. It was common practice for artists to be granted permission to bring sketching equipment and even paints, canvas and an easel to set up in museum galleries in order to copy from the masterpieces of the collection. This is still occasionally practised in museums today and is a critical way for artists to learn from their forebears.

But as we can see here, Ingres was not content with just making another copy. When we compare Ingres' drawing to Leonardo's original, it becomes clear that there are some notable differences.

For example, the facial features of Ingres' lady are slightly more rounded, with flatter cheeks, a more prominent nose and a mouth that forms into a narrower pout. The details of her clothing are also given much more careful attention, with every fold and crease now a much more prominent aspect of the picture.

In Leonardo's painting, these details fade much more into the shadows. The light background in the drawing is the inverse of the black background in the painting. This comparison points to the different strengths of these two mediums: Ingres's greyscale drawing allows for more visible detail and intricate lines, and he has kept it almost completely devoid of shadow. Leonardo's painting relies on dramatic lighting that causes a sense of recession into the shadows.

Given the ways his drawing diverges from Leonardo's original, Ingres wanted his study to be just as much a display of his own artistic vision as much as it was a tribute to Leonardo's.

These different examples demonstrate the way master studies present a unique field of work for artists. Sometimes, they are not just about learning from past masters, but also present an opportunity to challenge them or to prove an equality in skill. Like a great musician tackling a sonata by Beethoven, a master study is a means by which an artist can objectively compare their own talent to that of their forebears.

George Bothamley, writer and artist.

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation