Thus, three 19th-century artists who were formerly listed as Russian now have been listed as Ukrainian in the captions of their work on the website of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Those are Arkhyp Kuindzhi, Ilya Repin, and Ivan Aivazovsky. At least in the case of Aivazovsky, this relabeling is terribly misguided.

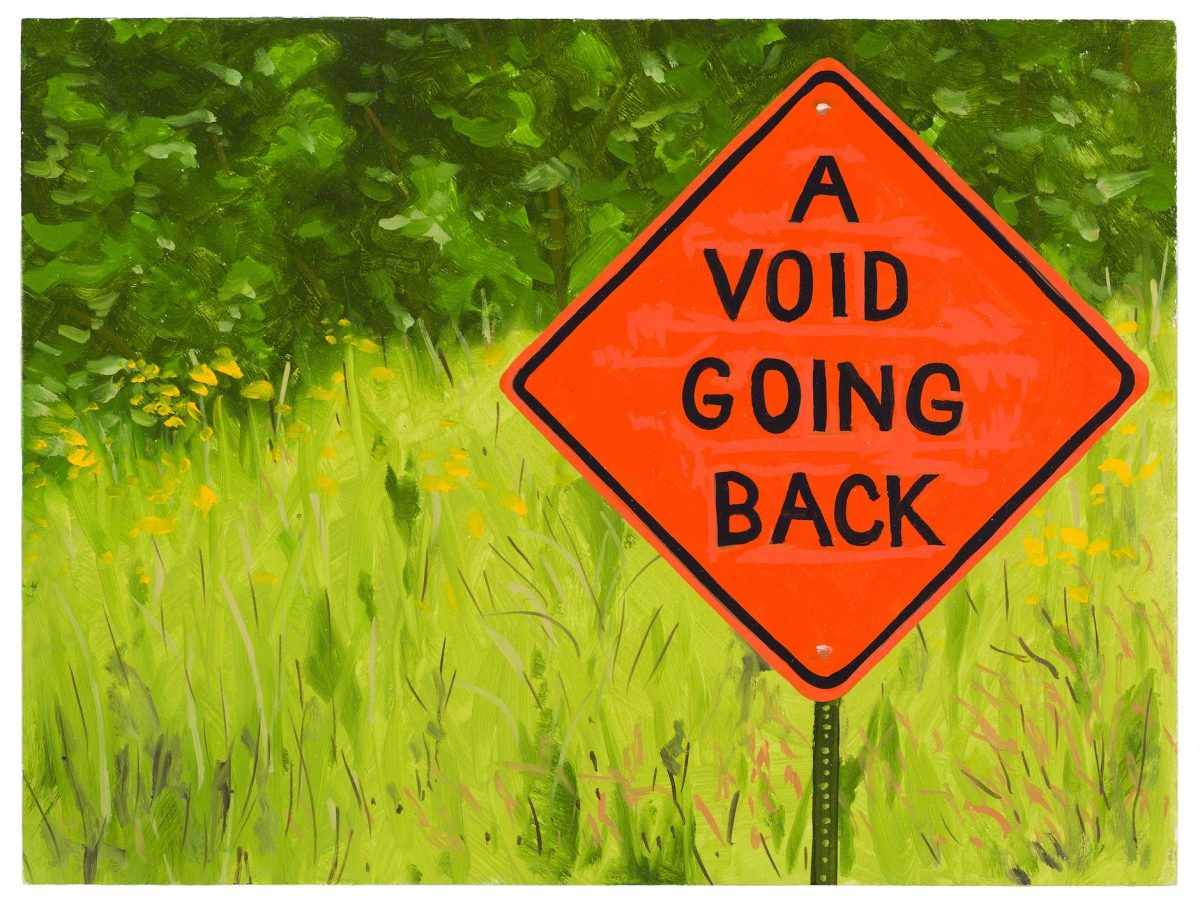

We may understand the “decolonization of Ukrainian art underway in leading US art museum,” as the Kyiv Post put it, but we cannot understand the replacement of ignorance shown in the previous identification by a new type of ignorance.

Misplaced identifications have been common in the past. It is not the first time that Aivazovsky (1817–1900), a painter rightly recognized as of Armenian origin on The Met’s website, was identified as Russian. That’s because he was born in the Russian Empire and his baptismal surname Aivazian was Russified as Aivazovsky, a common practice in Russian domains.

However, does the fact that Aivazovsky was born in Feodosia, a port on the Black Sea in the peninsula of Crimea where he was mostly based throughout his life, make him Ukrainian? The fact that he was baptized as Hovhannes Aivazian in the Armenian Apostolic Church St. Sargis of Feodosia and buried in the same church 83 years later, along with his strong identification with the Armenian people, should already tell us something about his identity. He did not belong to the Ukrainian Church and did not speak Ukrainian. His birthplace was part of the Crimean Khanate (1443–1783), a vassal to the Ottoman Empire that was later under the control of the Russian Empire until 1917, nearly two decades after Aivazosvky’s death, and part of Russia until 1954.

While we understand the complexities of identities going across the boundaries of time and space, one may ask why The Met applies a double standard. Is there a reason for Aivazovsky or Kuindzhi (of Pontic Greek descent) to be identified as “Ukrainian,” while, for instance, Paul Klee is mentioned as “German, born Switzerland” and Arshile Gorky as “American, born Armenia”? Is it possible to list Aivazovsky as Armenian first and thus give a more accurate depiction of his identity?

Should we be looking forward to The Met showcasing some Armenian, Greek, or Jewish artists born in Constantinople before 1930 (or Istanbul afterwards) and listing them as Turkish? Everything is possible in this time and age when the porous borders of state, nation, and religion are blurred and conflated for political and ideological reasons.

Russian imperialism over Ukraine and its culture, and former Soviet peoples in general, does not deserve any praise for quite good reasons, but misplaced decolonization efforts should not be praised either.