Frans de Waal, biologist who championed animal intelligence and emotion, dies at 75

The primatologist found parallels between human behavior and that of our evolutionary cousins.

Frans de Waal, the prolific Dutch-American primatologist and author whose research revealed the depth and breadth of emotion and intelligence in nonhuman animals, died from stomach cancer on March 14 in Stone Mountain, Georgia, according to the New York Times. He was 75.

“It’s difficult to sum up the enormity of Frans de Waal’s impact, both globally and here at Emory,” said Lynne Nygaard, chair of Emory University’s department of psychology, in a statement on the school's website. “He was an extraordinarily deep thinker who could also think broadly, making insights that cut across disciplines. He was always ready to participate in an intellectual discussion.”

De Waal’s studies of animal behaviors that were once ascribed solely to humans—fairness, empathy, altruism, reciprocity, self-recognition, conflict resolution, grief, and consolation—played a pivotal role in bringing about the acceptance of animal emotion as a valid line of scientific inquiry.

(What are animals thinking? They feel empathy, grieve, seek joy just like us.)

Early life

Born in the city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands, in 1948, de Waal showed an early enthusiasm for animals, keeping (with varying degrees of success) a modest menagerie that included mice and jackdaws, relatives of crows. Some of the jackdaws, de Waal recounted in stories, would even fly to and from school with him each day.

After an underwhelming introduction to biology in high school, de Waal almost went on to study mathematics or physics. It was his mother who reminded him of his long-standing interest in animals, and in 1966, he began an undergraduate degree in biology at the Catholic University of Nijmegen (now the Radboud University Nijmegen) in the Netherlands.

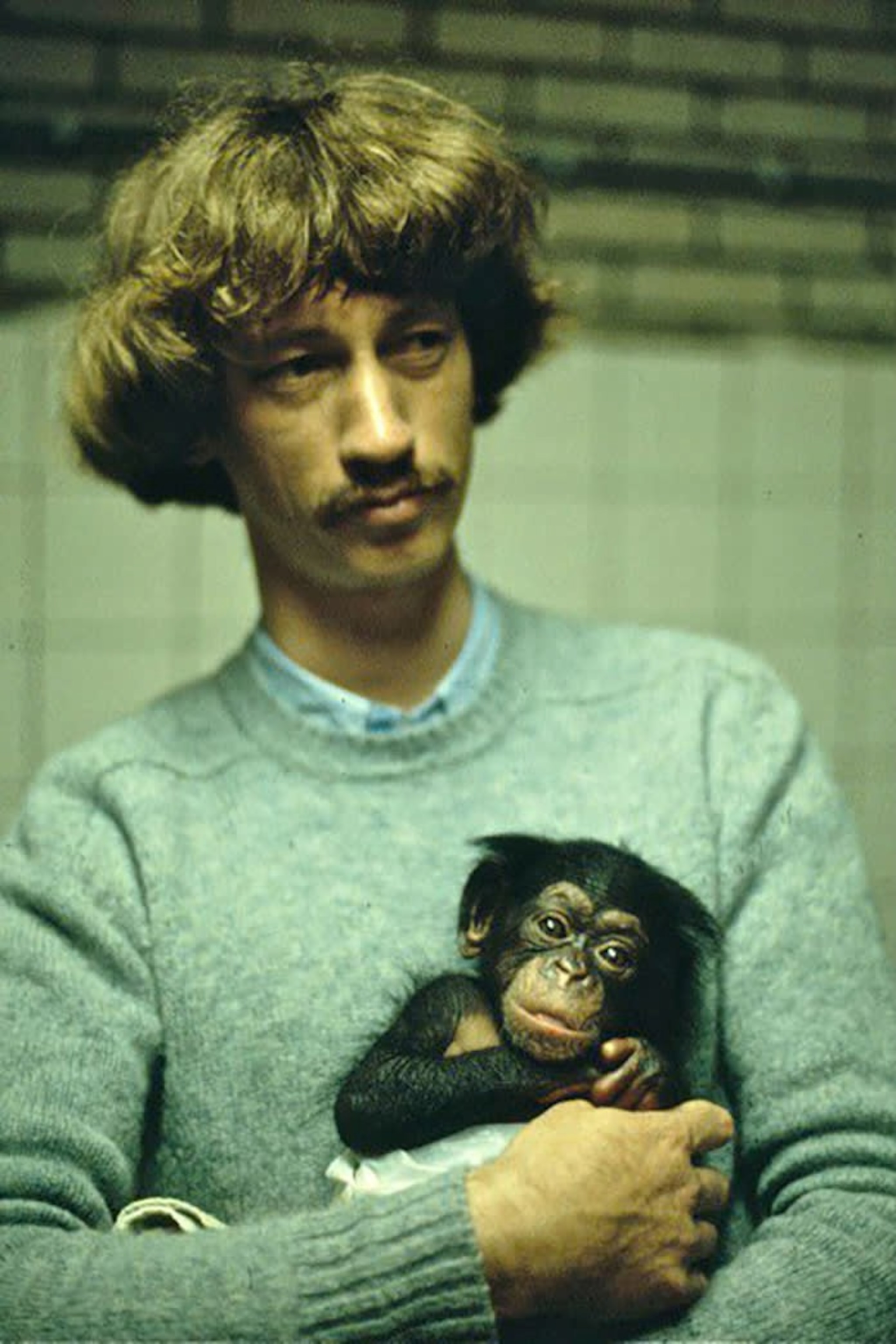

De Waal’s entry into primate research was the result of a happy coincidence. He found biology to be somewhat dry, with its heavy focus on anatomy. The psychology department, where he spent time during his studies to earn extra money, happened to have two chimpanzees. This early exposure to primates would prove pivotal.

At a career retrospective in 2014, he regaled the audience with a tale of how the chimps would become sexually aroused when female colleagues passed the enclosure. He and a male colleague sought to test this by dressing up as women—apparently eliciting little to no interest from the male chimpanzees. It was, he conceded, an imperfectly designed experiment.

In 1977, de Waal received his doctorate in biology from Utrecht University, where he worked under professor and mentor Jan van Hooff, an expert in primate facial expressions. His dissertation looked at aggression and alliance formation in macaques.

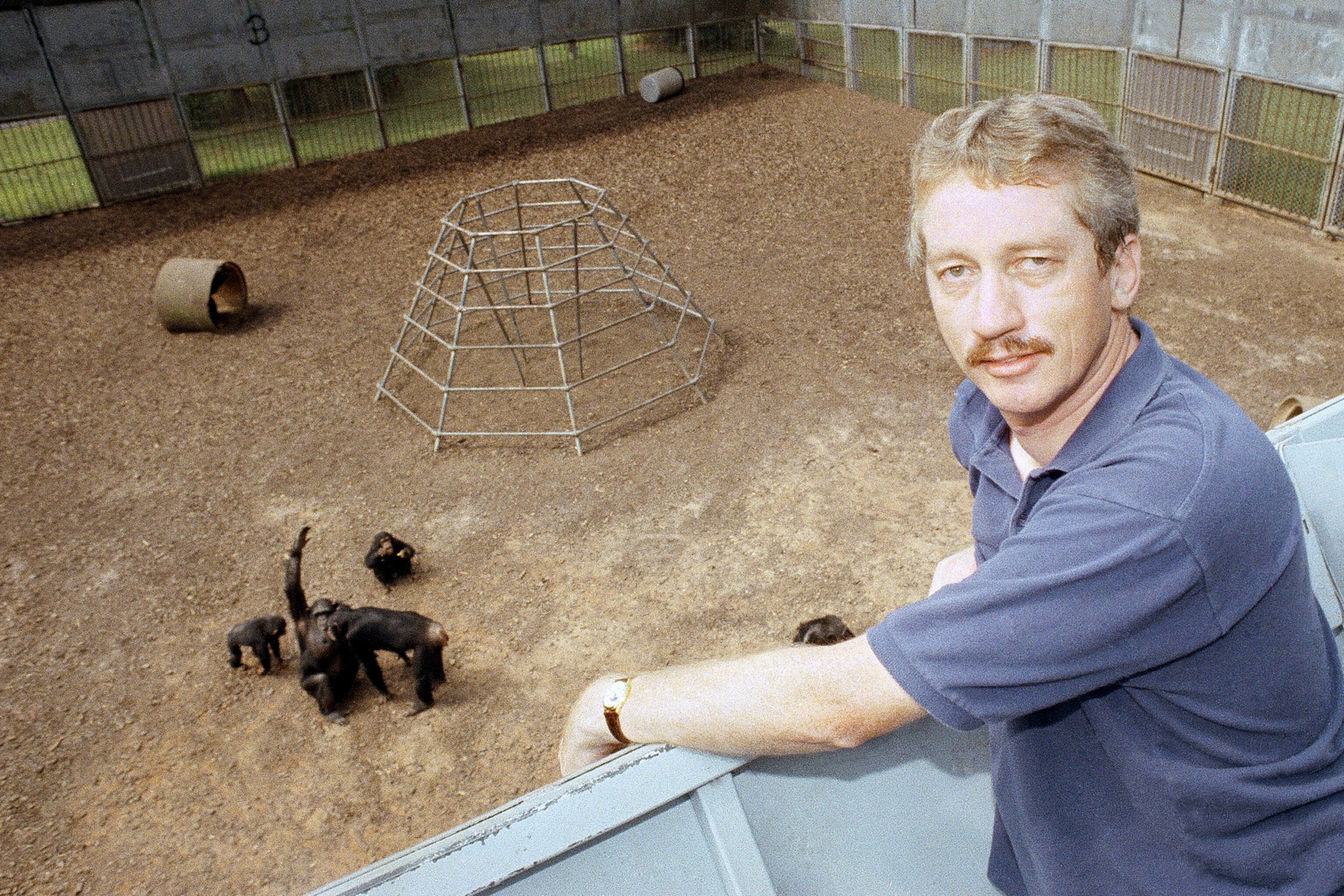

He went on to serve as the C.H. Candler Professor in the psychology department of Emory University, in Georgia, and as the director of the Living Links Center at Emory’s Yerkes National Primate Research Center. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the National Academy of Sciences, and the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences, and occupied the role of editor-in-chief of the journal Behaviour from 2011 until 2024.

Breakthrough research

De Waal was frustrated with what he saw as a misplaced focus on aggression in primates; he was more interested in cooperative behavior and cognition. In what became a theme throughout his career, his studies of reconciliation and conflict resolution among primates were initially controversial and challenged the prevailing orthodoxy, but as the data were confirmed his ideas went on to gain widespread acceptance.

In the field of animal emotion, de Waal made his biggest mark. The post-Darwin consensus on animal behavior steered away from anthropomorphizing, or attributing to animals any characteristics perceived as uniquely human. De Waal saw this as a form of “anthropo-denial.” In his view, the question wasn’t whether or not animals had emotions; rather, it was how to study them.

The species perhaps most closely associated with de Waal is the bonobo, a close relative of chimpanzees that he first saw at a zoo in the Netherlands. It only took a minute, he would later relate, for him to realize they were different from chimps in both vocalization and behavior. He knew immediately that he needed to study them. Colleagues at the time couldn’t understand why he would want to spend time on what were then referred to as “pygmy chimps,” often derided as “the poor man’s chimpanzee.”

But he found a home for his research at San Diego Zoo and in 1983 received a National Geographic Society grant to study the zoo’s bonobos.

His work raised the profile of bonobos, the species he dubbed the “make love, not war” primate and called “peace-loving hippies.”

He contended that science’s focus on the chimpanzee as our closest living relative made little sense, and suggested that bonobos were also genetically similar to humans, therefore equally deserving of attention.

De Waal found the establishment somewhat prudish where the subject of sex—a cherished form of recreation for the bonobo—was concerned. At a 2014 symposium celebrating his career, he joked with the audience:

“I talked openly about the sexual behavior,” he said. “At the time, American and Japanese scientists who worked on bonobos—they knew what they did, but they didn’t talk about it. They were too shy about it!” He noted that Americans would describe bonobos as “fairly affectionate. And you know, if I were affectionate like that in the streets of New York I would get arrested immediately!”

When he started to put a book on bonobos together with wildlife photographer Frans Lanting, which features explicit sexual pictures of the apes, “we had to put it in the contract with our publishers that they would not censor our pictures.” Their photo book, Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape, published in 1997. Lanting paid tribute to his colleague in an email to National Geographic in May 2022:

“Frans de Waal’s work helps us understand who we are in the context of our next of kin on the tree of life. He has a unique ability to connect the evolutionary dots for a broader audience without sacrificing the scientific principles he was equally well-versed in. He is a great storyteller and not afraid to raise questions which fuel the public conversation about the deep connections between us as humans with our nearest relatives in the great primate family we’re all part of,” Lanting said.

Legacy

Primatologist and professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Karen Strier, told National Geographic in an email that de Waal unquestionably changed the way science views (and treats) primates.

“His most influential insights, in my view, can be divided into three areas,” says Strier. The first was that “nonhuman primates are more thoughtful than we thought, in both their cognitive abilities and in their empathy and morality,” she says, spurring more ethical treatment of primates. The second: Frans’ “fine-grained observations of individuals in social groups, powerful experimental and analytical designs, and informative comparisons among closely-related species” showed the scientific community that a tremendous amount can be observed and concluded about primates through non-invasive techniques. The third, Strier says, is that “through his work we have gained new perspectives” on the evolution of our own behavior as humans.

To de Waal, the existence of emotions and behaviors such as fairness in animals was obvious. The question was simply how to quantify and qualify these traits. His approach to experiments and observation yielded hard data, bringing scientific credibility to previously elusive concepts. In 2003, de Waal and colleague Sarah Brosnan conducted experiments in which capuchin monkeys were “paid” with either cucumber pieces or much-coveted grapes in return for completing a task. Footage of the disgruntled capuchin given the inferior cucumber went on to be a viral hit, clearly demonstrating that capuchins understand the concepts of fairness and injustice.

In 2011, de Waal and colleagues went on to prove that chimpanzees are inherently altruistic as well. When given a choice between helping themselves, or themselves and another, they will choose the latter.

He authored 16 books, which have been translated into over 20 languages and sold millions of copies worldwide. It was Chimpanzee Politics: Power and Sex Among Apes that catapulted his work into the popular imagination, drawing parallels between the behavior of our primate relatives and that of another species: human politicians.

De Waal referred to writing books as his parallel career. Inspired by ethologist and author Desmond Morris, he understood the value of popularizing science. With a flair for presenting a compelling narrative underpinned by scientific rigor, de Waal achieved the rare feat of attaining and maintaining both popular success and the respect of his scientific peers. His 2016 book Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? landed on the New York Times best sellers list, and his 2019 book Mama’s Last Hug won the PEN/E.O. Wilson Literary Science Award.

“It is rare for a scientist to have such an enormous positive impact on both the academic field in which they work and the public’s perception and understanding of that field,” Joshua Plotnik, an elephant cognition expert who earned his Ph.D. under de Waal, told National Geographic by email. “Frans [was] most certainly one of those scientists.”

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- U.K. treasure hunters are finding ancient artifacts—who gets to keep them?U.K. treasure hunters are finding ancient artifacts—who gets to keep them?

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

Science

- Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

Travel

- Germany's iconic castle has been renovated. Here's how to see itGermany's iconic castle has been renovated. Here's how to see it

- This tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyramidThis tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyramid

- Food writer Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavoursFood writer Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavours

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches