Which animals were on Noah's ark? These are history’s theories.

Only two animals are mentioned by name in the biblical tale—so for centuries artists have filled in the gaps with both fantastic tales and emerging science.

An epic flood. A heavenly edict. A charismatic menagerie. The Book of Genesis’ tale of Noah’s ark has earned its place as one of the Bible’s most famous. But which animals accompanied Noah on his self-made ship?

It’s a complicated question given the Bible’s silence on the species involved. Just two animals are mentioned by name in the tale—a dove and a raven, which Noah sent to find out if the flood had died down enough to make Earth habitable yet.

But that hasn’t stopped artists and scientists from making plenty of colorful—and sometimes ludicrous—guesses about the animals that made it onto the ark. Their theories ultimately reveal more about the eras in which they lived and the steady progress of scientific discovery than that ark itself.

Medieval renderings of Noah’s ark

Speculation about the animals of the ark is nearly as old as the Bible itself, and the earliest surviving image of a biblical narrative, cast on a third-century A.D. coin, depicts Noah’s ark. Made in what is now Turkey, the bronze shows the ark and two birds thought to reference the dove that Noah sent to find out if Earth had dried.

“We’re naturally drawn to stories about animals,” says Elizabeth Morrison, senior curator of manuscripts at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and curator of a variety of exhibitions about medieval animal illustrations.

Medieval minds in particular were fascinated by the natural world and sought to attach religious importance to every aspect of the Noah story, from the symbolism of the church-like ark to Noah’s supposed discrimination between pure and impure animals aboard his ship. Medieval artists and scientists often compiled lists of these animals—and colorful stories that tied into the Noah narrative—in bestiaries, or books with moral messages and plenty of pictures.

“The Noah’s ark story has the added advantage of having such drama,” Morrison says. “It’s like the end of the world—except you get to save animals.”

As a result, illuminated texts and medieval paintings burst with imaginative depictions of animal life among sea and land-dwelling creatures thought to have been saved on the biblical boat.

Cows and giraffes and … unicorns?

But which animals specifically did medieval artists depict? European artists with little knowledge of the breadth of global wildlife, included animals that would have been familiar from everyday life. For example, the Old English Hexateuch, an 11th-century Anglo-Saxon manuscript, shows cows, goats, and pigs—common European domesticated animals—leaving the ark in twos.

(Why Sir Isaac Newton believed a comet caused Noah's flood.)

More exotic animals depicted in other manuscripts, though, indicate medieval Europe’s increased contact with the rest of the world, first through trade and then through international exploration.

Fifteenth-century carvers at the Norwich Cathedral in England depicted Noah with not just cattle and birds, but a monkey—an animal that, though not native to northern climes, would have been familiar due to the menageries and court entertainments of the time. Giraffes, peacocks, and lions were also depicted in ark imagery of the era.

The Norwich carvers included another, more fanciful animal aboard the ark—a unicorn.

“People in the Middle Ages didn’t have Wikipedia, jet planes, or a sense of travel,” Morrison says. “They didn’t really have access to information.”

Given this limited scope, she says, people of the era were apt to interpret tales of previously unknown animals according to their own imaginations. As a result, beasts like unicorns, gryphons, and dragon–like creatures are often portrayed alongside real-life animals in bestiaries and illuminated texts depicting the ark.

(8 real-life “Fantastic Beasts” and where to find them.)

Emerging science shapes Noah’s ark theories

Medieval people may have thought that creatures like unicorns and dragons were plausible. But the tale of Noah’s ark was largely interpreted as symbolic until after the Reformation in the early sixteenth century, when scholars began to engage with it as a literal event from history.

This presented real challenges for intellectuals tasked with squaring the story’s details with both emerging scientific concepts and the amazing variety of animals discovered during an upsurge in European seafaring and exploration. This led to what scientific historian Ruth Hill calls “the original and most contested origins of species debate prior to Charles Darwin”—and a spate of competing theories about animals on Noah’s ark.

For instance, Jean Borrell, a French mathematician also known as Johannes Buteo, contended that only 93 types of mammals had been aboard the ark—and the rest, he argued, spontaneously arose out of the mud and thus did not need saving. Spanish Jesuit Benito Periera similarly theorized that many insects like flies would not need berths on the ship because they were generated from the corpses on which they fed. And British explorer Sir Walter Raleigh hypothesized that “hybrid” species like mules were not on the ark because they had simply not existed at the time.

Hybrid madness—and the birth of the concept of species

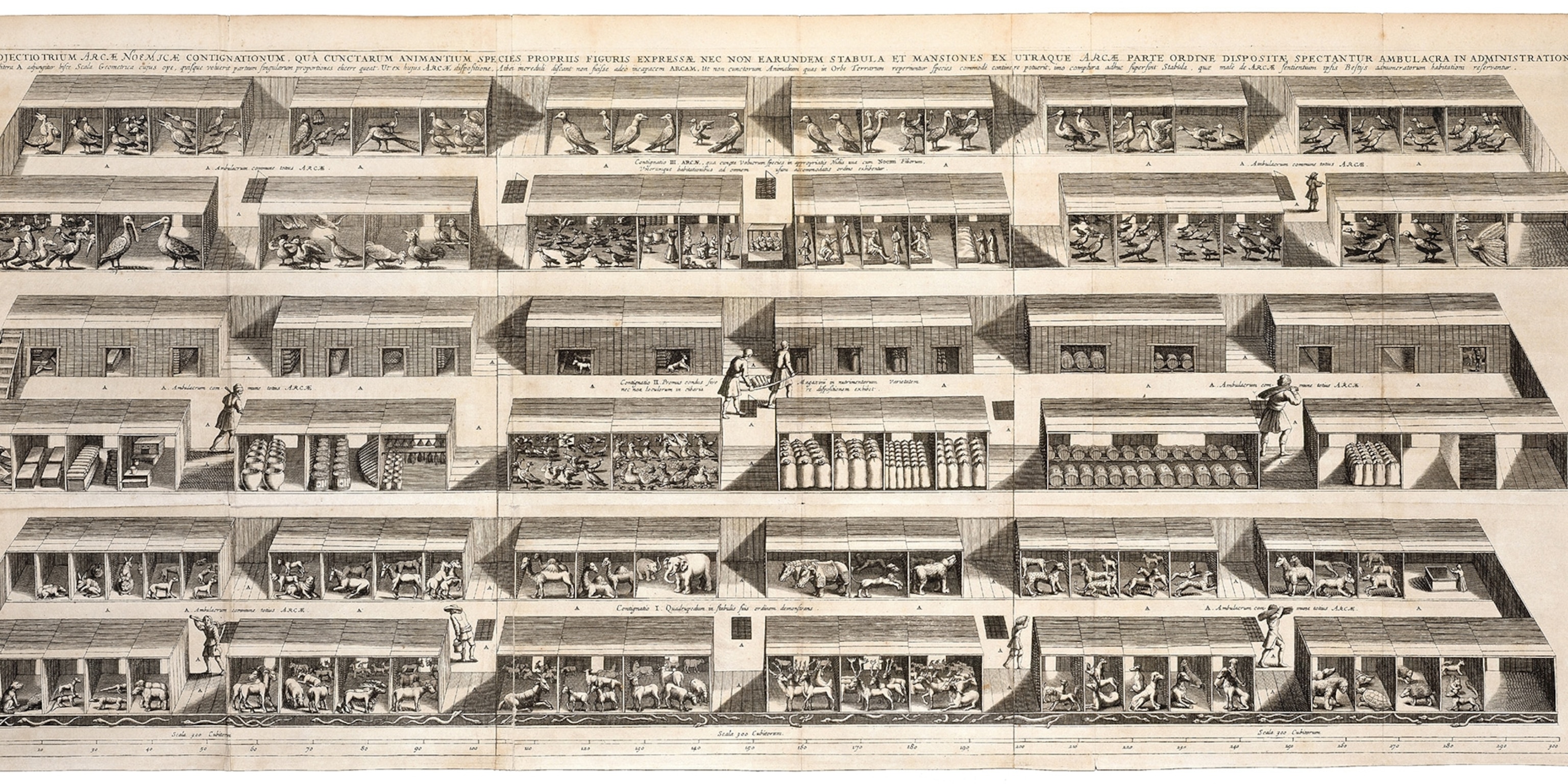

By the 17th century, it was becoming even more difficult to square new scientific discoveries with biblical stories like that of Noah. One such researcher, German polymath and Jesuit Athanasius Kircher, attempted to do just that with Arca Noë. The 1675 book looked at all aspects of selecting, caring for, and fitting all those animals on the ark.

Kircher’s ideas about life on the ark were particularly memorable—especially because he took the idea of “hybridization” entertained by Raleigh and other scientific minds to an absurd extreme. He argued that many land species were actually hybrids and could be safely left off of the ark: these included giraffes, a camel-leopard hybrid, and armadillos as the product of turtle-porcupine mating. (Neither theory was true.)

Because of the possibilities presented by these so-called “hybrids,” Kircher imagined Noah would only have needed 130 types of four-footed mammal, 30 snake species, and 150 bird species to repopulate Earth after the flood. “Kircher carried his style of research about as far as it could go, which was to the point of collapse,” note scientists Olaf Breidbach and Michael T. Ghiselijn in the Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences.

But in fact, the ideas birthed by Kircher, Buteo, and others actually ended up helping birth the concept of biological species beginning in the sixteenth century. The idea was unheard of before these mental experiments with Noah’s menagerie, which pushed scientists like Buteo and Kircher to classify and rank animals in an attempt to determine whether they’d have been ark-worthy.

The concept of species came about just in time—as Hill notes, the idea that all animals could have been passengers on the ark was quickly becoming “highly implausible.” After centuries of sometimes fanciful, sometimes analytical looks at biblical animals, scientists and artists eventually moved on—inadvertently leaving behind pivotal stepping stones in our understanding of the natural world.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

Travel

- Germany's iconic castle has been renovated. Here's how to see itGermany's iconic castle has been renovated. Here's how to see it

- This tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyramidThis tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyramid

- Food writer Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavoursFood writer Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavours

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches