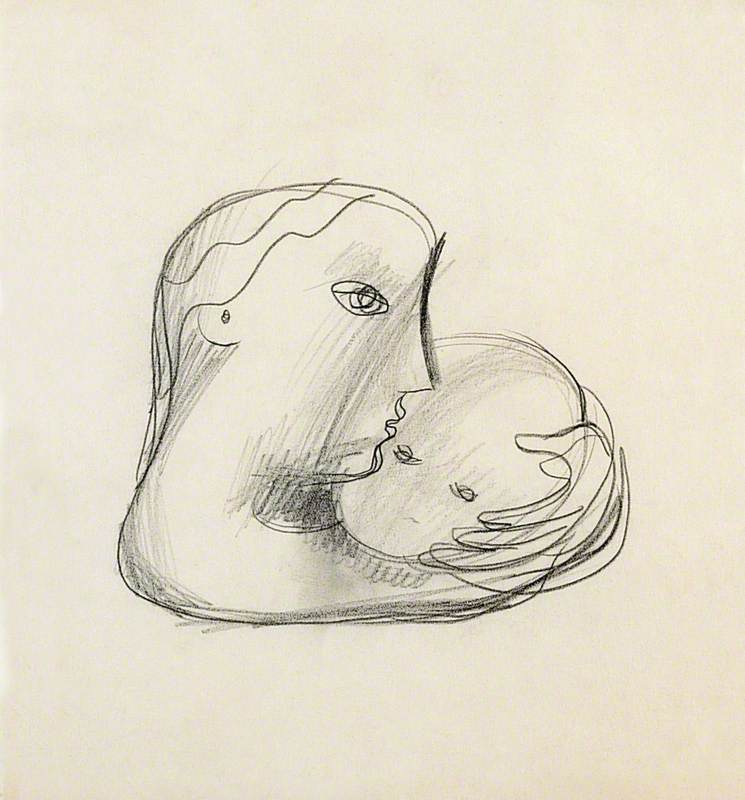

A female figure fills a large, vivid, sparsely worked surface. Cascading blue forms swirl around the meticulously drawn subject, who awkwardly twists toward the viewer.

As a work, Figure in Blue is neither formal nor illustrative but seems to exist outside these categories. Artist Claudette Johnson takes liberties with line to amplify the sense of movement, just as she uses exaggerated outlines and bright colours to add drama and emphasis. The energetic lines and idiosyncratic perspective nod to abstraction without ever fully embracing it, reflecting Johnson's larger ethos of originality and nuance.

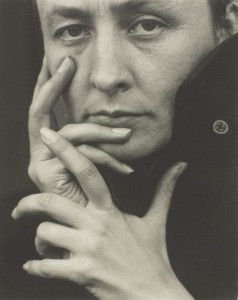

Johnson was born in 1959 in Manchester. During her studies, she kept up a fateful fascination with African American writers such as Alice Walker, Audre Lorde and Toni Morrison. They fostered a literary space which located the identity of Black women in the troubled perspectives of the past. Johnson's early drawings nod to these powerful histories. 'I'm interested in giving space to Blackwomen presence. A presence which has been distorted, hidden and denied. I'm interested in our humanity, our feelings and our politics; somethings which have been neglected,' she said in Claudette Johnson: Pushing Back the Boundaries, an exhibition catalogue published in 1990. Like Lorde, who often spoke of how she started writing because of a need to create what wasn't there, Johnson's work creates something that has its own presence.

Trilogy (Part One) Woman in Blue

1986

Claudette Johnson (b.1959)

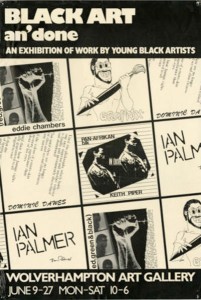

Johnson's journey as one of a group of pioneering Black feminist artists began while she was an art student at Wolverhampton Polytechnic. She befriended Eddie Chambers in her final year, an artist and art historian from Wolverhampton who worked with collage and explored racial identity through his work. At one exhibition, as Johnson records in a 1991 interview, he contributed a work with the text 'who nu black now na go black again.' She called it 'an irresistible call to action.'

Chambers also invited Johnson to give a paper at the First National Black Art Convention during their regular meetings as part of the Wolverhampton Young Black Artists. She used the work made during her university studies to discuss images of Black women in histories of art and feminist politics. This polemical lecture led to further friendships with Sonia Boyce, Veronica Ryan and Lubaina Himid. Johnson contributed three large works on paper to the exhibition 'The Thin Black Line', curated by the latter at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1985–1986.

Trilogy (Part Two) Woman in Black

1986

Claudette Johnson (b.1959)

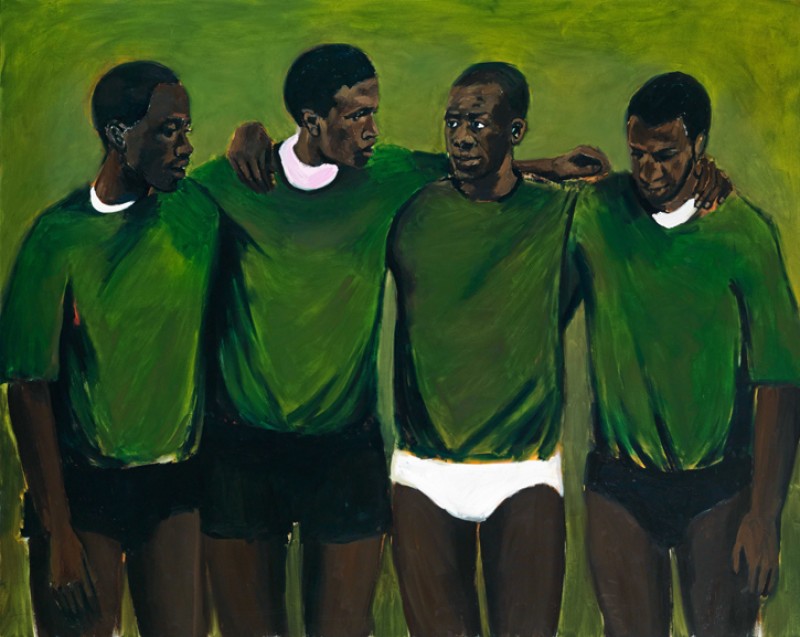

One of the works, Trilogy (Part Two) Woman in Black shows a woman staring at us in mute solitude. The large scale, striking composition and choice of colour palette all communicate the defiant presence at the heart of Black women's struggle for visibility. Reflecting with Emma Ridgeway, then Modern Art Oxford's Chief Curator, Johnson said, 'it was much more about the sitter's planting themselves very strongly and confidently and taking up as much space as they could.'

Claudette Johnson pointed out the spatial logic in her works on paper, saying 'the space assigned to black women within the media and within British society; I think it is a very small, twisted space [...] so I usually invite sitters to take up space in a way that is reflective of who they are.' For Johnson's sitters, occupying space can be uncompromising and powerful precisely because it is uncontainable within the confines of the work's surface. The artist overthrows tired notions of classical portraiture and pushes back the boundaries of the paper. In Untitled, 1990 (Standing Woman), a naked female figure spreads her legs, which has one cropped at the hip and the other at the thigh. The jarringly cropped body disrupts traditional systems of composition and portraiture. The woman looks directly at the viewer, defiant rather than self-conscious in her nakedness.

In the early 1980s – around the time Johnson took a photography job at the Lenthall Road Workshop in Hackney, a feminist screen-printing collective – she told the Feminist Art News that 'the active involvement of the women in my drawings, who are so obviously engaged in creating themselves, acts to challenge the entrenched passivity and negative sexuality of the "nude" tradition in painting'. As ever, Johnson displays a penchant for resisting traditional art historical narratives. She joins a wider legacy of artists in the twentieth century driving a shift from passive to assertive subjects, including throughout performance and conceptual art as well as figurative work like Johnson's. Johnson's figures are literally engaged, both with the artist and the viewer. Standing Figure is filled with movement. The thin, swirling lines afford a special clarity to the fabric of the woman's dress, which twists with her body turning towards us.

In the large-scale Untitled, a work on paper depicting Johnson's close friend, the British artist Brenda Agard, three vertical bands of unequal width present the subject as complex and multifaceted – one has a cream white shirt, another has part of the shirt missing. Two are frontally static while the third appears to be in motion.

The drawing shows a hybrid world in which the tripartite formal structure imitates its source material: photographic test strips. She worked on this huge sheet of paper taped to the wall of her kitchen, building layers of pastel and blending them with her fingers over a period of three months. The unplanned, undulating lines came first in dry pastel. Afterwards, Johnson painted over these forms with blocks of watercolour and gouache before adding a final layer of coloured pastel 'to make things more solid', as the artist put it. Beneath the image, the texture of the paper can often be seen, providing a haptic background.

Figuration remains a fascination for Johnson in her drawing because she 'could tell personal and in its widest sense political truths,' combining the body's strength and political visibility. See her Figure in raw umber, who twists towards the viewer with a defiant gaze. This young Black woman with her close-cropped hair, leather jacket and firm jawline hits us with a Schiele-esque rebellious stare. The sitter is London filmmaker and artist Beverly Bennett, whose works revolve around drawing and collaborating with friends. This drawing establishes a present-ness for its subject without creating objectification, calling on Bennett's arresting look to assert her agency in a space which has frequently distorted, hidden and denied the existence of Black women.

Trilogy (Part Three) Woman in Red

1986

Claudette Johnson (b.1959)

Johnson spoke of wanting a less knowing relation to portraiture, and continually erased what she thought was its specificity. Art historian Dorothy Price sensed this refusal: 'Her sitters resist the desires of hungry viewers, keen to assign a name in the illusion that such knowledge will somehow bestow meaning; Johnson's works are resolutely not portraits.' If so, the artist reimagines figuration on new terms. She might have adopted bell hooks' notion that space for Black women was one that can only emerge 'from an imaginative inventiveness since there is no body of images, no tradition to draw on'.

Trilogy (Part Two) Woman in Black (above) shows a vast expanse of negative space, blank shapes abutting highly textured ones, that allows the figure to breathe. The deliberate tension between absence and presence in this and other works of the 1980s – the voids in and around the body – become an important aspect of the ideas that Johnson was working through in the context of the period's emerging discourse on Black British art.

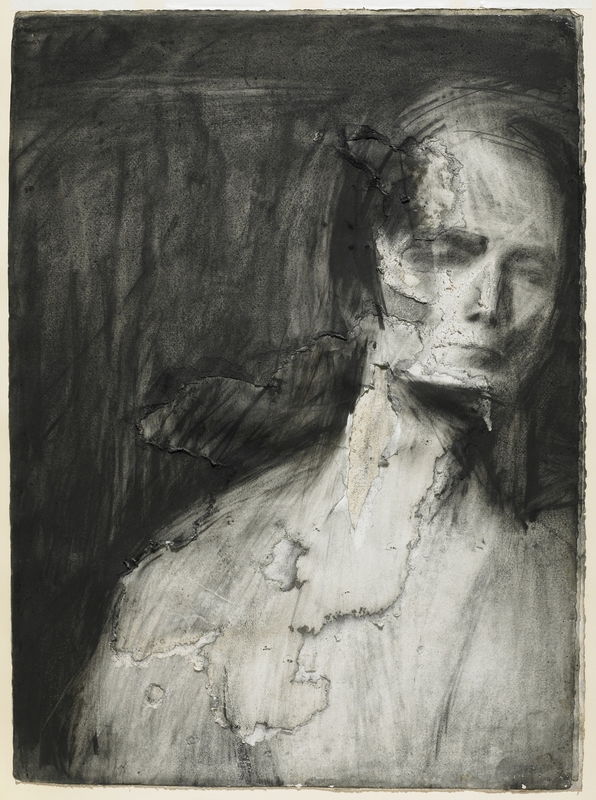

Last year, Johnson told The New York Times about her favourite artwork, Rembrandt's A Young Woman Sleeping (c.1654). 'It does everything I want my drawings to do.' He used brown wash not to intensify form but to make the atmosphere present itself, creating a space suggested only by shadow and the gradation of light around the woman's body.

A Young Woman Sleeping

c.1654, paper, by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669)

The tones, simplicity of line and intimacy of the drawing echo Johnson's work, especially Figure in raw umber. Making the body twist or subjecting it to calm serenity is also part of Rembrandt's drawing. Lines drawn by the Dutch artist in this washy work on paper act as a prophetic commentary on Johnson's pursuits, distilling this tension between tranquillity (in the figure's expression) and movement (in the turning body). By establishing her legacy in the long history of figurative art in Europe, Johnson claims space which has been much too frequently distorted, hidden and denied to her.

Matthew Cheale, writer, editor and art historian

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Lubaina Himid, Claudette Johnson, & Maud Sulter, Claudette Johnson: Pushing Back the Boundaries, exhibition catalogue, Rochdale Art Gallery, 1990

Claudette Johnson, Claudette Johnson: Portraits from a Small Room, exhibition catalogue, 198 Gallery, London, 1995

Dorothy Price & Barnaby Wright (eds.), Claudette Johnson: Presence, exhibition catalogue, The Courtauld, London, 2023

Emma Ridgeway (ed.), Claudette Johnson: I Came to Dance, exhibition catalogue, Modern Art Oxford, 2019