Why has Alabama executed a man using nitrogen gas?

- Published

A death row inmate has been executed using a novel method. Why have authorities in Alabama used nitrogen gas, and why is it controversial?

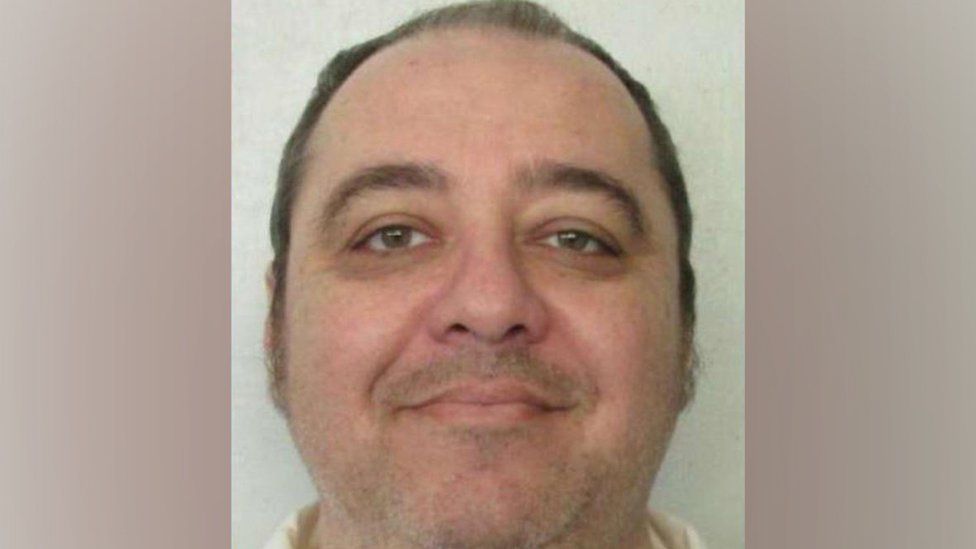

Kenneth Eugene Smith was originally scheduled to be put to death with lethal drugs in November 2022.

Prison staff inserted one intravenous line, but two lines were required to administer the lethal injection.

After they struggled for an hour to insert the second IV, the execution was called off.

But Smith - who was convicted of the murder-for-hire of a preacher's wife in 1988 - was eventually executed using nitrogen gas instead.

It's a controversial method that had never been used before by a US state.

And it represents the latest step in the search for a new way to execute convicted criminals - even as the death penalty has become less popular over time.

The problems with lethal injection

Around half of US states still have death penalty laws. Execution methods vary, but some states still allow execution by hanging, firing squad or the electric chair.

According to the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC), a not-for-profit organisation that is critical of how executions are administered, no method has been found to violate the US Constitution's ban on "cruel and unusual punishments", although some state courts have outlawed some methods.

In recent decades, however, most states have converged on lethal injection - the administration of intravenous drugs that sedate and kill the convict - as the main execution method.

Texas was the first state to execute a convicted criminal with lethal injection, in 1982.

Last year, 24 people were executed in the US - most of those in Florida and Texas, and all by lethal injection.

The process, however, is not always straightforward. Several months prior to Smith's previous botched execution, Alabama authorities failed to put to death another death row inmate, Alan Miller, also because of difficulties inserting an IV needle. Several other lethal injection executions have also not gone according to plan.

And states have recently had difficulty in obtaining lethal injection drugs. In some cases, drug manufacturers won't sell them, or no longer produce them.

The UK and the European Union banned exports of the chemicals in 2011, and five years later American drugs giant Pfizer, the last open-market source of lethal injection drugs, announced it would no longer sell them to be used in executions.

The result is that states have been scrambling for other ways to execute prisoners.

Texas, for instance, has sourced its deadly chemicals from a secret list of private "compounding pharmacies", which mix their own drugs.

What is nitrogen hypoxia?

Prison officials strapped a mask to Smith's face and administered the pure nitrogen gas.

The gas itself is not poisonous - nitrogen makes up more than three-quarters of the earth's atmosphere.

But in pure concentrated form, breathing in the gas chokes off oxygen to the brain, a process called nitrogen hypoxia.

The use of nitrogen gas in executions has been approved by three states, including Alabama in 2018, and has withstood various legal challenges since.

Why is it controversial?

Watch: How nitrogen became a form of execution in the US

The procedure had critics even before Smith's execution.

"It's an experimental procedure," says Dr Jeff Keller, President of the American College of Correctional Physicians. "Many things can go wrong."

Deborah Denno, a criminologist at Fordham Law School who specialises in research into death penalty methods, said the procedure "is supposed to be painless".

"But I have to emphasise - that's in theory," she says.

"These masks don't usually don't fit people," she says. "They're not airtight, air can get in."

Smith could have started vomiting or survived the attempted execution with brain damage, she says.

Proponents of the method reject criticism and point to examples of nitrogen hypoxia occurring in industrial accidents, with victims apparently becoming unaware of what is happening to them.

One study prepared for Oklahoma lawmakers considering whether to allow nitrogen gas executions cited research that concluded "without oxygen present, inhalation of only 12 breaths of pure nitrogen will cause a sudden loss of consciousness".

Alabama State Attorney General Steve Marshall has called nitrogen gas "perhaps the most humane method of execution ever devised".

Some witnesses to Smith's execution, though, said he did not lose consciousness within seconds and that he inhaled the gas for many minutes, thrashing all the while, before finally succumbing.

Unpopular sentence

The flurry of attention over Smith's execution comes as enthusiasm for the death penalty has ebbed across much of the US.

The number of executions is down substantially from a peak of 98 in 1999, according to the DPIC.

Not only are fewer death sentences being carried out, in fewer states - just 10 have executed a prisoner in the last decade - but fewer death penalties are being handed out by courts.

"We've seen a big change in American support for the death penalty," says Robin Maher, the DPIC's executive director.

Polling organization Gallup, which has been tracking public attitudes towards the death penalty for nearly a century, says that 53% of Americans favour the death penalty for convicted murders.

That figure is down from a high of 80% which the survey registered 30 years ago.

Ms Maher says a variety of factors resulted in the death penalty becoming less common - not only botched executions, but nearly 200 exonerations of death row inmates, legal changes which prohibit mentally impaired people and juveniles from being put to death, and the increasing reluctance of juries to hand down death sentences.

"I expect that trend will continue," she says.

With reporting by Bernd Debusmann Jr and Anahita Sachdev

Related Topics

- Published22 January

- Published26 January