Why scratching an itch actually makes it worse

Why scratching an itch actually makes it worse

Understanding the chemical process of itching and why scratching is futile.

© American Chemical Society (A Britannica Publishing Partner)

Transcript

LAUREN: Poison ivy, wool sweaters, mosquito bites, bugs crawling up your arm-- you itchy yet? If so, you might want to think twice about scratching.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Hey, Chemketeers. Lauren here. We've all been itchy at one point or another. Maybe you got a bug bite. Maybe you had a run in with poison ivy.

[SIGHING]

I mean the other poison ivy. Anyway, this type of temporary itch all starts when a molecule called an allergen works its way into your skin. When a bug bites you, it injects an allergen. And when poison ivy brushes against you, it transfers an oily allergen called urushiol.

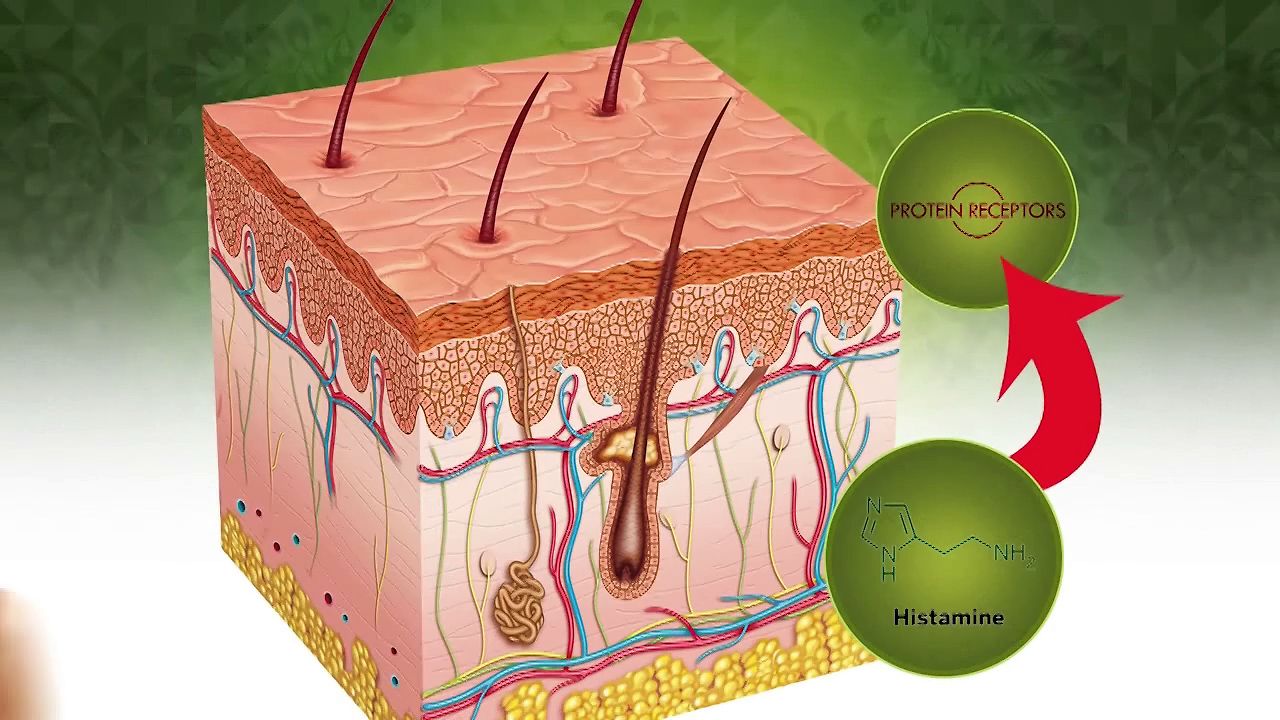

Your body recognizes these allergens as foreign invaders and sends in the troops. In this case, those troops are immune cells called mast cells. These mast cells do a bunch of good things like helping to heal wounds. But they also release a chemical called histamine, and that's where the trouble starts.

Histamine makes its way to nerve cells and the top most layers of your skin. And it sticks to protein receptors there. When it binds, it triggers a cascade of molecular events that eventually causes the nerve cells to send an itch signal to your spinal cord and then on up to your brain.

Ever taken an anti-histamine? As its name suggests, this drug works against histamine by preventing the troublesome molecule from binding to your nerve cell receptors. No histamine binding, no itch signal.

OK. But what if you've just put on an itchy sweater? Say, because it's freezing. No anti-histamine needed. You can scratch away, right? Not so fast. Scientists now know why scratching an itch actually makes it worse.

Nerve cells that send its signals to the brain are hopelessly intertwined with the ones that send pain signals to your brain-- so much so that scientists still aren't quite sure how the brain knows pain from itch. But they do know that when you scratch an itch, you cause yourself a small amount of pain. And for a brief moment of sweet, sweet relief, the pain actually masks the itchy feeling.

Unfortunately, your brain then recognizes the pain signal and tries to dampen it by releasing serotonin. That's a neurotransmitter that regulates mood. The serotonin travels to your spinal cord where it activates nerve cells that generate itch signals.

So you see scratching an itch is a vicious cycle. You get itchy. Then you scratch. Then you get itchy again, and you scratch some more.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Hey, Chemketeers. Lauren here. We've all been itchy at one point or another. Maybe you got a bug bite. Maybe you had a run in with poison ivy.

[SIGHING]

I mean the other poison ivy. Anyway, this type of temporary itch all starts when a molecule called an allergen works its way into your skin. When a bug bites you, it injects an allergen. And when poison ivy brushes against you, it transfers an oily allergen called urushiol.

Your body recognizes these allergens as foreign invaders and sends in the troops. In this case, those troops are immune cells called mast cells. These mast cells do a bunch of good things like helping to heal wounds. But they also release a chemical called histamine, and that's where the trouble starts.

Histamine makes its way to nerve cells and the top most layers of your skin. And it sticks to protein receptors there. When it binds, it triggers a cascade of molecular events that eventually causes the nerve cells to send an itch signal to your spinal cord and then on up to your brain.

Ever taken an anti-histamine? As its name suggests, this drug works against histamine by preventing the troublesome molecule from binding to your nerve cell receptors. No histamine binding, no itch signal.

OK. But what if you've just put on an itchy sweater? Say, because it's freezing. No anti-histamine needed. You can scratch away, right? Not so fast. Scientists now know why scratching an itch actually makes it worse.

Nerve cells that send its signals to the brain are hopelessly intertwined with the ones that send pain signals to your brain-- so much so that scientists still aren't quite sure how the brain knows pain from itch. But they do know that when you scratch an itch, you cause yourself a small amount of pain. And for a brief moment of sweet, sweet relief, the pain actually masks the itchy feeling.

Unfortunately, your brain then recognizes the pain signal and tries to dampen it by releasing serotonin. That's a neurotransmitter that regulates mood. The serotonin travels to your spinal cord where it activates nerve cells that generate itch signals.

So you see scratching an itch is a vicious cycle. You get itchy. Then you scratch. Then you get itchy again, and you scratch some more.