Canada

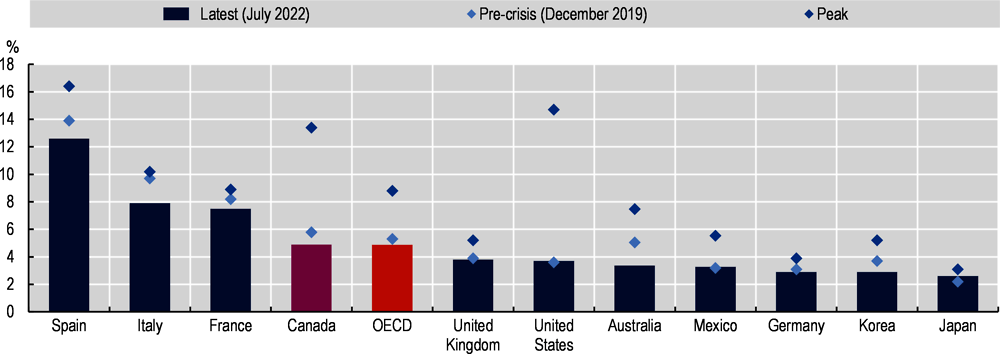

Total employment in the OECD returned to pre-crisis levels at the end of 2021 and continued to grow in the first months of 2022. The OECD unemployment rate gradually fell from its peak of 8.8% in April 2020 to a level of 4.9% in July 2022, slightly below the 5.3% value recorded in December 2019. However, the labour market recovery has been uneven across countries and sectors and is still incomplete, while its sustainability is challenged by the economic fallout of Russia’s unprovoked, unjustified, and illegal war of aggression against Ukraine.

At its peak, the unemployment rate in Canada reached 13.4% in Q2 2020. But by July 2022, it had come down to 4.9%, below the pre-crisis level of 5.8%.

The high peak unemployment rate highlights the different policy path that Canada took to manage the COVID-19 crisis relative to many other OECD countries. Instead of relying on job retention schemes, which reduced hours but kept workers connected to jobs, Canada relied more heavily on temporary lay-offs and enhanced unemployment benefits.

Labour shortages have emerged in this low unemployment environment, and job vacancy rates are now particularly high in certain sectors: construction (up 110% in early 2022 compared to early 2020), manufacturing (up 94%), health care and social assistance (up 91%), and accommodation and food services (up 88%).

Few OECD countries collect data, which allow the impact of the crisis on racial/ethnic minorities to be monitored. In most of those which do, the crisis affected racial/ethnic minorities disproportionally and, where information is available, the recovery of these groups has been slower. However, there are countries that fare better in this respect, showing that a worse impact for minorities is not a fatality: in New Zealand, racial/ethnic minorities have benefited from the recovery more than the majority group, reducing their employment gap in Q4 2021 relative to Q4 2019.

The employment recovery among Indigenous people in Canada was initially slower than among non-Indigenous people, but has since sped up. The employment rate among Indigenous people reached 57.7% in the three months ending August 2021, surpassing its pre-pandemic level of 56.2%, and reducing the employment gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Indigenous people have historically had poorer labour market and education outcomes linked to the ongoing impacts of colonisation.

However, the employment recovery among older Indigenous adults (55 or older) since the fall of 2021 was much weaker compared with Indigenous youth and core-aged adults due to greater rates of inactivity. Older workers, and in particular older Indigenous workers, have been more vulnerable to the economic and health impacts of COVID-19, and some may have opted to retire earlier than planned to avoid associated health risks.

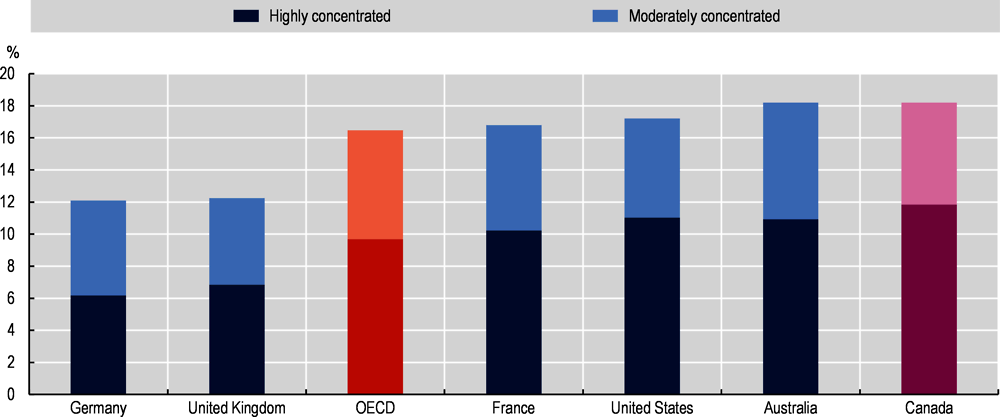

Labour market concentration, where few employers compete for workers, contributes to employer monopsony power. Monopsonistic employers can set wages unilaterally, leading to lower employment and wages. The largest cross-country analysis to date shows 16% of workers are employed in at least moderately concentrated labour markets. Reducing anticompetitive practices and expanding collective bargaining, among other policies, can curb monopsony power.

Canada’s business sector is more concentrated than the OECD average, with few employers competing for workers. In Canada, 18% of employees work in concentrated labour markets shared by fewer than seven firms (compared to 16% of employees in OECD countries on average). Canada’s rural labour markets are more concentrated than urban ones, and much more concentrated than rural labour markets on average for OECD countries (51% compared with 29% for OECD countries). Higher labour market concentration is associated with more demanding skill requirements in employers’ job postings.

OECD simulations suggest that if remote work were made available to all workers whose occupation is amenable, then labour market concentration would decline by 34% in Canada, resulting in a likely 1% increase in average real wages. This moderate increase shows that remote work alone is not sufficient to mitigate the impact of monopsony power. Other policies, such as fostering collective bargaining and more aggressive antitrust actions, are likely to have a greater effect.