Native Americans

Racism, 'Morbid Curiosity' Drove US Museums to Collect Indigenous Remains

In December 1900, John Wesley Powell received “the most unusual Christmas present of any person in the United States, if not in the world,” reported the Chicago Tribune.

The gift for this first director of the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of Ethnology was a sealskin sack containing the mummified remains of an Alaska Native.

The sender was a government employee hired to hunt Indian “relics,” who said the remains had been difficult to acquire because “to come into the possession of a dead Indian is a great crime among the Indians.”

The report concluded that it was the only “Indian relic" of this kind at the Smithsonian and it was “beyond money value.”

As it turned out, it was not the museum’s only Alaskan mummy. In 1865, even before the U.S. purchased Alaska from Russia, Smithsonian naturalist William H. Dall was hired to accompany an expedition to study the potential for a telegraph route through Siberia to Europe. In his spare time, he looted graves in the Yukon and caves on several Aleutian Islands.

After the U.S. sealed the deal with Russia, the San Francisco-based Alaska Commercial Company won exclusive trading rights and established more than 90 trading posts in Alaska to meet the U.S. demand for ivory and furs.

It also instructed agents “to collect and preserve objects of interest in ethnology and natural history” and forward them to the Smithsonian. Ernest Henig looted 12 preserved bodies and a skull from a cave in the Aleutians in 1874. He donated two to California’s Academy of Science and sent the remainder to the Smithsonian.

More than 30 years after the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act meant to return those remains, a ProPublica investigation last year estimated that more than 110,000 Native American, Native Hawaiian and Alaska Native ancestors remain in public collections across the U.S.

It is not known how many Indigenous remains are closeted in private or overseas collections.

“Museums collected massive numbers, perhaps even millions,” said anthropologist John Stephen “Chip” Colwell, who previously served as curator of anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. “Out of the 100 remains we [at the Denver museum] returned, I think only about five or seven individuals were actually even studied.”

So, what sparked this 19th-century frenzy for collecting human remains?

Reconciling science, religion

From the moment they first encountered Indigenous Americans, European thinkers struggled to understand who they were, where they came from, and whether they could be “civilized.”

The Christian bible taught them that all humans descended from Adam and that God created Adam in his own image. So why, Europeans wondered, did Native Americans, Africans and Asians look different?

Some Europeans theorized that all humans were created white, but dietary or environmental differences caused some of them to turn “brown, yellow, red or black.”

Other Europeans refused to accept that they shared a common ancestor with people of color and theorized that God created the races separately before he created Adam.

The birth of scientific racism

Presumptions that compulsory education and Christianization would force Native Americans to abandon their traditional cultures and become “civilized” into mainstream European-American culture proved untrue. So 19th-century scientists turned to advancements in medicine to “prove” the inferiority of Indigenous peoples.

“That’s when you see scientists like Samuel Morton, who invented a pseudoscience trying to place peoples within these social hierarchies based on their biology, and they needed bones to solidify those racial hierarchies,” said Colwell, who is editor-in-chief of the online magazine SAPIENS and author of “Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America's Culture.”

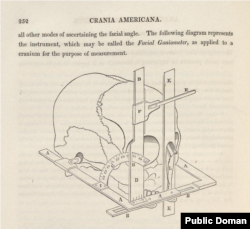

Morton was a Philadelphia physician who collected hundreds of human skulls of all races, mostly Native American, that were forwarded to him by physicians on the frontier. In his 1839 book "Crania Americana," Morton classified human races based on skull measurements. Morton's conclusions were used to support racist ideologies about the inferiority of non-white humans.

“They are not only averse to the restraints of education, but for the most part incapable of a continued process of reasoning on abstract subjects,” he wrote of Native Americans. “The structure of [the Native] mind appears to be different from that of the white man, nor can the two harmonise in their social relations except on the most limited scale.”

Despite Morton’s legacy as an early figure in scientific racism — ideologies that generate pseudo-scientific racist beliefs — his work earned him a reputation at the time as “a jewel of American science” and influenced the field of anthropology and public policy for decades.

In 1868, for example, the U.S. Surgeon General turned his attention away from the Civil War to the so-called “Indian wars” and instructed field surgeons to collect Native American skulls and weapons and send them to the Army Medical Museum in Washington “to aid in the progress of anthropological science.”

“For museums, especially the early years of collecting, it was a form of trophy keeping, a competition between museums,” Colwell told VOA. “And some of it was a competition between national governments to accumulate big collections to demonstrate their global and imperial aspirations.”

All the rest, he said, were fragments of morbid curiosity.

See all News Updates of the Day

Native American News Roundup, April 21-27, 2024

US House committee chair stresses tribal sovereignty

Oklahoma congressman Tom Cole is the first Native American to chair the powerful U.S. House Appropriations Committee, which passes bills to fund the federal government.

In a message to constituents Monday, Cole, a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma said, "It is important to remember that Native Americans are the First Americans. They are sovereign nations who governed themselves long before settlers arrived, and they continue to do so today.

"Through legally binding agreements, such as the federal trust responsibility, the United States is obligated to provide services and federal resources to tribes — a responsibility I have been and will continue to work to ensure is met," Cole wrote.

He also stressed the importance of raising congressional awareness about Native American issues, sovereign rights and the unique challenges facing tribal communities.

Read more:

Native Americans most likely victims of deadly police force

A Lee Enterprises' Public Service Journalism team has published the first of a series of stories from more than a year's research into why Native Americans are more likely than any other racial group to die in the hands of law enforcement.

The opening article focuses on South Dakota, home to nine federally recognized tribes, and cites poor funding for police in tribal communities and a lack of accountability for fatal law enforcement incidents. Their investigation also found that loved ones of Native Americans who die in jail or police shootings "struggle to access even the most basic information about how these deaths occur."

According to figures compiled by the Indigenous-led activist and advocacy group NDN Collective, Native Americans represent 8.2% of the South Dakota population but were victims in 75% of fatal police shootings from 2001 to 2023.

In its 2021 report to Congress, the Interior Department's Bureau of Indian Affairs said that its Public Safety and Justice Programs across Indian Country are funded at just under 13% of total need and that it would take an additional 25,655 new officers to adequately serve Indian Country.

As VOA has previously reported, South Dakota governor Kristi Noem has repeatedly criticized the Biden administration for failing to adequately fund tribal law enforcement.

Inadequate funding of tribal safety and justice programs is not a new problem. In July 2003, the U.S. Civil Rights Commission reported that per capita spending on law enforcement in Native American communities was about 60% of the national average.

Read more:

Navajo Nation to investigate abuse allegations

Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren says he welcomes an independent, fair and transparent investigation into allegations of sexual harassment and sexual assault within the office of the tribal president and vice president.

In a Facebook stream April 16, Vice President Richelle Montoya revealed that she was sexually harassed within the office of the president and vice president during an August 2023 staff meeting.

"I was made to feel that I had no power to leave the room, I was made to feel that what I was trying to accomplish didn't mean anything, that I was less than," she said.

She did not name the individual who harassed her, "for fear of retaliation."

In November 2023, Navajo Times reported that former employees had experienced sexual assault and sexual harassment in the same office.

Indigenous journalists call for greater representation in media

The president of the Indigenous Journalists Association, or IJA, this week called on the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues to better support Indigenous journalism

"Globally, Indigenous communities are ignored, misrepresented, maligned and in many cases dehumanized by media portrayals of our cultures, distinct issues and the challenges we face due to the impacts of colonization," said IJA head Christine Trudeau, a citizen of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation.

Fewer than half of 1% of newsroom employees identify as Indigenous, she said, adding that some of the most prestigious news outlets routinely stereotype — or disregard altogether — tribal nations.

"To fully realize self-determination, we must ensure that our cultures are accurately represented in the coverage of our communities," she said.

See Trudeau's full statement in the video above.

Feds return land to tribe in Illinois

One hundred seventy-five years ago, Shab-eh-nay ("Built Like a Bear"), chief of the Prairie Band Potawatomi in Illinois, returned home from an extended visit to Kansas to find that the U.S. government had illegally auctioned off more than 1,200 acres (485 hectares) of land promised under the Prairie du Chien treaty of 1829.

Late last week, the Interior Department announced it would place 130 acres (52 hectares) of the original Shab-ey-nay Reservation land into trust for the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, which is now the only federally recognized tribal nation in Illinois.

Read more:

North Carolina tribe opens medical cannabis dispensary

The Eastern Band of Cherokee, or EBCI, has opened the first cannabis dispensary in the state of North Carolina. The Great Smoky Cannabis Company opened on April 20, known for decades as the national cannabis holiday "4-20."

Marijuana is still illegal in North Carolina, but because the EBCI is a federally recognized sovereign nation, it can make its own laws. The tribe legalized medical marijuana in 2021 and voted to legalize recreational cannabis in September 2023.

North Carolina residents at least 21 years old can apply for a medical card from the EBCI cannabis control board. They will need to demonstrate they have one of 18 medical conditions that include anxiety, PTSD and cancer.

Read more:

What happened to Native American skull looted by Chicago reporter?

NOTE: This story contains culturally sensitive information that may be distressing for some readers. Caution is advised.

WASHINGTON — In the summer of 1889, a group of cynical Chicago crime reporters organized itself as the Whitechapel Club, taking the name of the London district where serial killer Jack the Ripper found his victims.

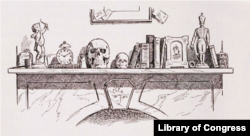

They rented rooms in a back-alley saloon, and in keeping with the club’s macabre theme, they decorated the walls with relics of war and crimes: revolvers, knives, hangman’s ropes.

“I suppose the gruesome [sic] connotations of the name led to our practice of collecting relics of the tragedies we were constantly reporting,” member Brand Whitlock recalled in his 1914 memoir, “Forty Years of It.”

John C. Spray, the former superintendent of the county’s mental asylum, donated skulls which Whitechapel member Chrysostom “Tomb” Thompson converted into tobacco jars, drinking cups and shades for gas lamps.

Whitechapel member and Chicago Herald writer Charles Goodyear Seymour was among the correspondents who covered the 1890 Wounded Knee massacre of as many as 300 Miniconjou and Hunkpapa Lakota men, women and children in South Dakota. He returned home with a collection of war relics, including a woman’s ghost shirt — white cotton, embroidered with yellow — and Native American skulls, according to Brand.

Seymour also traveled to the Blackfeet and Piegan reservation in Montana, recounted in a May 12, 1891, article for the Herald titled, “How to Steal a Skull.” Seymour described how he and an Army infantry lieutenant sneaked into a graveyard at night and managed to retrieve two skulls.

“There is not much fun in robbing a graveyard,” he wrote, “even if it is an Indian graveyard.”

'A large collection'

The Whitechapel Club’s reputation helped grow its ghastly collection.

“It became the practice of sheriffs and newspapermen everywhere to send anything of that kind to the Whitechapel Club. The result was that within a few years, it had a large collection of skulls of criminals,” Whitlock would later write.

Among Seymour’s contributions was the skull of an “Unc’papa [Hunkpapa Lakota]” woman, described by Whitechapel member George Frank Lydston as “the wife of one of the leading malcontents in the recent outbreak” at Wounded Knee.

Lydston was a Chicago urologist and professor of criminal anthropology at the Chicago-Kent College of Law. He was also a staunch eugenicist who believed that the shape of people’s skulls indicated intelligence or “undesirable” traits such as criminality and other forms of “degeneracy.” Lydston, who was a member of the Whitechapel Club, used some of the skulls to support his research.

The Wounded Knee skull was among several that Lydston presented in a 1904 book, “The Diseases of Society: The Vice and Crime Problem.”

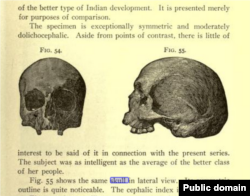

He concluded little about the Hunkpapa skull, other than that she had an elongated and symmetrical head and was likely “as intelligent as the average of the better class of her people.”

So, who was she and what happened to her skull? Did she really die in the massacre, or had Seymour invented her identity to add to the skull’s grisly appeal?

Shortly before his death in 1920, Joseph Horn Cloud, a Miniconjou Lakota Wounded Knee survivor who later co-founded the Wounded Knee Survivors Association, compiled a list of individuals who survived or were killed in the massacre.

In 2019, the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe's West River Eagle published a separate list, date unknown.

Most were Miniconjou followers of Spotted Elk from the Cheyenne River Reservation or Hunkpapa followers of his half-brother Sitting Bull from the Standing Rock Reservation.

Comparing both lists, VOA was able to identify three Hunkpapa women who died in the massacre: Zintaikiwin (Bird’s Belly), Itewakanwin (Sacred Face), and Wannawega tawicu (Wife of Breaks Arrows with Foot). Two women died later of wounds received in the massacre: Wowacinyewin (Dependable) and Kicinajinwin (Wife of Stands With).

It is not known if their bodies were recovered by their families or buried in the mass grave at Wounded Knee.

From Chicago to Washington

In May 1891, Lydston traveled to Washington to present his findings at the annual convention of the American Medical Association. He brought with him a trunk full of skulls, The Washington Post reported, including that of the Hunkpapa woman.

Lydston boasted that it was he, not Seymour, who had been sent to Wounded Knee and retrieved the skull, adding that while he was there, he had been taken prisoner and held for more than three weeks. He did not say by whom.

“He was allowed just enough to live on, and was a walking skeleton when released,” the Post reported.

Lydston told the newspaper he was donating the skulls to AMA.

“Dr. Lydston says the club did not want to give up these specimens, but he persuaded the members into doing so,” the Post concluded. “He says that no amount of money would buy the specimens now in the hall of the Whitechapel Club.”

VOA reached out to AMA about the Hunkpapa skull.

“Based on a review of AMA’s archives, the AMA neither currently nor in the past possessed human tissue or specimens,” a spokesperson responded via email. “In official proceedings, there are mentions of exhibits that contained human remains, but these were presented at meetings and then went on tour or home with the exhibitor.”

The AMA says one of those exhibits at its Chicago headquarters was dismantled in 1935 and its contents donated to the city’s Museum of Science and Industry.

Kathleen McCarthy, head curator at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry, told VOA, “We have no record of a donation of skulls from the American Medical Association in 1935. In all my time here, I have not heard of or seen any skulls in the collection.”

What if Lydston did not donate the Whitechapel Club skulls as he claims and kept them for himself?

After the club dissolved in 1895, Lydston published “Over the Hookah: The Tales of a Talkative Doctor” in which an aging “Dr. Weymouth” relates a series of anecdotes to a young medical student.

Though it is a work of fiction, Lydston acknowledges in the preface that the tales are “taken from life.”

In one chapter, the student describes a large cabinet in the older doctor’s library. It contains a collection of “curious and ghastly skulls” that were “the doctor’s pride.”

Lydston died of pneumonia in 1923. In his last will and testament, he left all property to his wife. But there is no record of the contents of that property.

The 1990 Native American Graves and Repatriation Act, NAGPRA, requires museums and federal agencies to take an inventory of all human remains and funerary objects in their collection and work with tribes to return them. Updated rules give them until 2029 to comply.

“The law is very clear that institutions do not own native bodies or cultural items unless they can prove a right of possession,” said Shannon O’Loughlin, a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and CEO and attorney for the Association on American Indian Affairs. “That means that there had to have been voluntary consent at the time of taking of the Native ancestor or other cultural items.”

Nor did Congress provide a remedy for cases in which private collectors or non-federally funded organizations hold Native American remains and related artifacts.

If the Lydston family donated the Hunkpapa skull to a medical school or other public institution covered by the law, she may one day be returned to her lineal descendants and the Hunkpapa community.

Native American news roundup, March 31-April 6, 2024

Updated standards on race and ethnicity data will benefit Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders

The federal government’s Office of Management and Budget has revised standards for collecting and presenting race data to ensure the diversity of the U.S. population is adequately represented.

Among the most affected will be Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, who have previously been lumped into a single category. Now they will be allowed to identify as, for example, Fijian, Tahitian, Samoan or Chuukese.

Members of the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus, or CAPAC, described the changes as a “historic milestone” for Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, or AANHPI, communities.

“As CAPAC has consistently emphasized, grouping our AANHPI communities together often masks the disparities that certain racial or ethnic groups face, including on economic prosperity, health outcomes, home ownership or educational attainment, and make government programs and services less responsive and effective,” said CAPAC chair, U.S. Representative Judy Chu, a Democrat from California.

Read the White House announcement here:

Governor, tribes, continue to clash in South Dakota

South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem released a statement Tuesday calling on tribes to “banish cartels from tribal lands.”

“The cartels instigate drug addiction, murder, rape, human trafficking and so much more in tribal communities across the nation, including in South Dakota,” Noem said.

She has repeatedly suggested that tribal leaders are misusing federal funds. She has also criticized President Joe Biden for failing to adequately fund tribal law enforcement.

During a special session in January, Noem told state lawmakers that South Dakota has been “directly affected” by an invasion of drug and human traffickers from the southern U.S. border and that cartels were working inside reservations in the state.

In a March town hall meeting, she alleged that tribal leaders were personally profiting from cartels.

Noem has also called for the government to conduct “public and comprehensive single audits” of all federal funds allocated to South Dakota’s nine Native American tribes.

The Single Audit Act requires an annual audit of all nonfederal entities, including tribes that spend over $750,000 in Federal Financial Assistance.

Indian Country Today reports that a search of the Federal Audit Clearinghouse shows that most South Dakota tribes regularly completed audits — at least up until 2020, when “an influx of funding for COVID-19 relief caused issues backlogging the process and overwhelming the treasurers.”

This week’s statement noted that following Noem’s call for an audit, “multiple members of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, including tribal councilmembers, unveiled serious allegations of corruption within tribal government.”

"Video of these comments will be made available upon request," it said.

At VOA’s request, Noem’s press secretary sent four video clips but failed to specify where they came from or how they were obtained.

VOA determined that they had been clipped from Oglala Lakota Sioux, or OST, tribal council meetings March 26-27 as seen on KOLC- TV's YouTube page, in which council members alleged the misuse of federal emergency funds by the tribe’s housing authority and questioned why the tribe was contracting to hire “Mexicans from Texas” when unemployment on the reservation stands at 80%, among other complaints.

Tribal leaders in South Dakota have expressed outrage over her remarks, accusing her of being racist and working to perpetuate stereotypes.

This week, the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe banned her from their reservation, following in the footsteps of the OST, which banned her from Pine Ridge in February.

Handful of Native American tribes will experience total solar eclipse

On Monday, a total solar eclipse will cross the United States from Texas to New York. Anyone inside its 115-mile-wide path (185 kilometers) of totality will be able to see the moon fully block the face of the sun. Anyone outside of that path will see a partial eclipse.

A map of the eclipse’s path reveals that tribal nations in only four states will experience totality: the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe in Texas, the Choctaw Nation in Oklahoma, some Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in New York and the Penobscot Nation in Maine.

The federal government recognizes 574 tribes, 347 of them in the lower 48 states.

No federally recognized tribes reside in the other states over which the eclipse will travel. Those states are Arkansas, Tennessee, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio and Pennsylvania — landscapes where prior contact and policies of forced removal eliminated hundreds of vibrant Indigenous communities.

Nor do any federally recognized tribes remain in Vermont, New Hampshire, Georgia, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, the District of Columbia or West Virginia.

"Rezbians" addresses same-sex love on reservations

VOA reporter Gustavo Martinez Contreras reported this week on an Indigenous graphic artist in New Mexico who is using a comic book to tell a story about same-sex love and identity on a Native American reservation.

Native American artist tells tale of love, identity

An Indigenous graphic artist in the Southwest U.S. state of New Mexico is using a comic book to tell a story about same-sex love and identity on a Native American reservation. Gustavo Martínez Contreras has our story from Albuquerque.

Uranium being mined near Grand Canyon as prices soar

The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that comes as global instability and growing demand drive uranium prices higher.

The Biden administration and dozens of other countries have pledged to triple the capacity of nuclear power worldwide in their battle against climate change, and policy changes are being adopted by some to lessen Russia's influence over the supply chain.

But as the U.S. pursues its nuclear power potential, environmentalists and Native American leaders remain fearful of the consequences for communities near mining and milling sites in the West and are demanding more regulatory oversight.

The new mining at Pinyon Plain Mine near the Grand Canyon is happening within the boundaries of the Baaj Nwaavjo I'tah Kukv National Monument that was designated in August by President Joe Biden. The work was allowed to move forward since Energy Fuels Inc. had valid existing rights.

Low impact with zero risk to groundwater is how Energy Fuels spokesperson Curtis Moore describes the project.

The mine will cover 6.8 hectares (16.8 acres) and operate for just a few years, producing about 907,000 kilograms (about 2 million pounds) of uranium — enough to power the state of Arizona for at least a year with carbon-free electricity, he said.

"As the global outlook for clean, carbon-free nuclear energy strengthens and the U.S. moves away from Russian uranium supply, the demand for domestically sourced uranium is growing," Moore said.

Energy Fuels, which also is prepping two more mines in Colorado and Wyoming, was awarded a contract in 2022 to sell $18.5 million in uranium concentrates to the U.S. government to help establish the nation's strategic reserve for when supplies might be disrupted.

Amid the growing appetite for uranium, a coalition of Native Americans testified before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in late February, asking the panel to pressure the U.S. government to overhaul outdated mining laws and prevent further exploitation of marginalized communities.

Carletta Tilousi, who served for years on the Havasupai Tribal Council, said she and others have written countless letters to state and federal agencies and have sat through hours of meetings with regulators and lawmakers. Her tribe's reservation lies in a gorge off the Grand Canyon.

"We have been diligently participating in consultation processes," she said. "They hear our voices. There's no response."

Numerous legal challenges aimed at stopping the Pinyon Plain Mine repeatedly have been rejected by the courts, and top officials in the Biden administration are reticent to weigh in beyond speaking generally about efforts to improve consultation with Native American tribes.

It's just the latest battle over energy development and sacred lands, as tribes in Nevada and Arizona are fighting the federal government over the mining of lithium and the siting of renewable energy transmission lines.

The Havasupai are concerned mining could affect water supplies, wildlife, plants and geology throughout the Colorado Plateau, and the Colorado River flowing through the Grand Canyon and its tributaries are vital to millions of people across the West.

For the Havasupai, their water comes from aquifers deep below the mine.

The Pinyon Plain Mine, formerly known as the Canyon Mine, was permitted in 1984. With existing rights, it was grandfathered into legal operation despite a 20-year moratorium placed on uranium mining in the Grand Canyon region by the Obama administration in 2012.

The U.S. Forest Service in 2012 reaffirmed an environmental impact statement that had been prepared for the mine years earlier, and state regulators signed off on air and aquifer protection permitting within the last two years.

"We work extremely hard to do our work at the highest standards," Moore said. "And it's upsetting that we're vilified like we are. The things we're doing are backed by science and the regulators."

The regional aquifers feeding the springs at the bottom of the Grand Canyon are deep — around 304 meters (nearly 1,000 feet) below the mine — and separated by nearly impenetrable rock, Moore said.

State regulators also have said the area's geology is expected to provide an element of natural protection against water from the site migrating toward the Grand Canyon.

Still, environmentalists say the mine raises bigger questions about the Biden administration's willingness to adopt favorable nuclear power policies.

Using nuclear power to reach emissions goals is a hard sell in the western U.S. From the Navajo Nation to Ute Mountain Ute and Oglala Lakota homelands, tribal communities have deep-seated distrust of uranium companies and the federal government as abandoned mines and related contamination have yet to be cleaned up.

Taylor McKinnon, the Center for Biological Diversity's Southwest director, said allowing mining near the Grand Canyon "makes a mockery of the administration's environmental justice rhetoric."

"It's literally a black eye for the Biden administration," he said.

Teracita Keyanna with the Red Water Pond Road Community Association got choked up while testifying before the human rights commission in Washington, D.C., saying federal regulators proposed keeping onsite soil contaminated by past operations in New Mexico rather than removing it.

"It's really unfair that we have to deal with this and my children have to deal with this and later on, my grandchildren have to deal with this," she said. "Why is the government just feeling like we're disposable. We're not."

In Congress, some lawmakers who come from communities blighted by past contamination are digging in their heels.

Congresswoman Cori Bush of Missouri said during a congressional meeting in January that lawmakers can't talk about expanding nuclear energy in the U.S. without first dealing with the effects that nuclear waste has had on minority communities. In Bush's district in St. Louis, waste was left behind from the uranium refining required by the top-secret Manhattan Project.

"We have a responsibility to both fix — and learn from — our mistakes," she said, "before we risk subjecting any other communities to the same exposure."