The plan sounds so reasonable on its face: We’ll all get together for Thanksgiving, but only after everyone—every last member of the family, no matter where they’re coming from or how they’ll get there—has had the chance to get a proper Covid test.

It isn’t only for the holidays. For months now, I’ve watched various acquaintances and their families decide to break the rules of social distancing in accordance with this same and suspect rule of thumb: It’s totally OK to meet up for a weekend trip ... as long as everyone has gotten tested; it’s fine to get together for a barbecue, or a visit with Grandma … just as soon as everyone has gotten tested.

Let me put this as clearly as I can: As a means of eliminating risk in the midst of a pandemic, the everyone-has-gotten-tested method is utterly absurd.

It’s true that getting a positive result tells you some crucial information: It’s time to cancel all your plans and isolate until you’re past the point of infectiousness. A negative test, though, doesn’t guarantee that anyone is Covid-free, and it’s never license to let down your guard. You might, for instance, contract the virus in the interim between being tested and receiving your results, or between getting your results and seeing your friends and family. (The testing site itself could even be where that happens.) Even if you assume these tests are 100 percent accurate, they’ll only tell you what your status is at the specific time the test is done.

Of course, the tests are not 100 percent accurate. In practice, their error rates may be even higher than the chance that you’re infected in the first place. The probability that you’ll receive a wrong result on any medical test depends not just on the test’s innate accuracy but on your baseline risk. Even a very good test will turn out more false positives than real ones if you go in as someone who isn’t likely to have the disease. Conversely, getting a negative result won’t give you that much information you didn’t have before. It might only increase your confidence at the margins, say from 95 to 98 percent, that you’re not already sick.

Covid testing is important, as a rule—it’s how we can identify people who have the coronavirus so they can separate themselves and stop the chains of transmission. Where people are coming together repeatedly in shared spaces, as in schools and workplaces or on sports teams, frequent testing can reduce transmission and outbreaks—but only when it’s paired with a robust system for isolation and contact tracing. As I’ve written here previously, testing alone isn’t enough; for disease surveillance to make a difference, it must be used alongside behavioral interventions such as masking and social distancing. If you’re assuming that a negative test means you can give up on those behaviors—that you can safely gather for dinner at a grandparent’s house or spend a weekend in a cabin with your buddies—then you’re asking for trouble.

It’s a lesson demonstrated by our current president. White House staff thought that if you tested negative, you were totally clear to go about your life with no masks and no distancing, says A. Marm Kilpatrick, an infectious disease researcher at UC Santa Cruz. That’s how Donald Trump and at least three dozen of his associates ended up with the virus. The same faulty reasoning explains the Covid outbreak of 116 cases at a boys’ overnight summer school retreat in Wisconsin, which was traced back to a student who had received a negative test just days before attending the retreat. Students at the camp were high-school age, and the rules for taking part were reminiscent of Kim Kardashian’s island birthday party of the thousand memes: All attendees were required to quarantine for a week before traveling to the event, wear masks during travel, and show proof of a negative PCR test result no more than seven days before they arrived. Once there, counselors and students were not required to mask and mixed freely with one another … kind of like how people who have tested negative might behave at a family gathering for Thanksgiving.

The everyone-gets-tested strategy makes a bit more sense if you think of it as a form of risk reduction, rather than a guarantee of safety. But even framed that way, it doesn’t make a ton of sense. Life in the pandemic requires making tradeoffs, and you may well decide that getting together with loved ones is worth whatever dangers it may bring. But if you really want to mitigate that danger, you should focus on what works best—and universal, one-off screening within your friend group isn’t it.

The best approach, says Kilpatrick, would be for everyone to go into full quarantine (that means no grocery shopping or other interactions with people) for two weeks prior to the visit, and then travel by car without coming into close contact with anyone else along the way. He acknowledges that this obviously isn’t going to be practical for most people. Short of that, you and your loved ones might each agree to go into full quarantine for several days—which is better than nothing—while continuing to practice masking and social distancing as much as possible.

If you can all add a test on top of that, so much the better. According to Gretchen Snoeyenbos Newman, an infectious disease physician at Wayne State University, the best time for those tests would be five to seven days after your last contact with someone outside your household. (Others have proposed a strict, eight-day quarantine with a Covid test at the tail end of it. Either way, this approach still involves a lot of time in isolation.) But, again, any such strategy requires a lot of assumptions—that getting tested does not itself put you in contact with people who are infected, and that it’s locally available for people without symptoms, and that you’ll get your results in a reasonable amount of time. Otherwise, you may as well not bother.

Instead of relying on a test to give you a green light, it’s better to do all you can to avoid exposures in the first place. With Covid cases climbing fast, and vaccines that may become available in early 2021, the stakes are even higher than they were before. Canceling Thanksgiving with Grandma means you all miss that human contact this year, but it might also ensure that she’s around for the next family gathering.

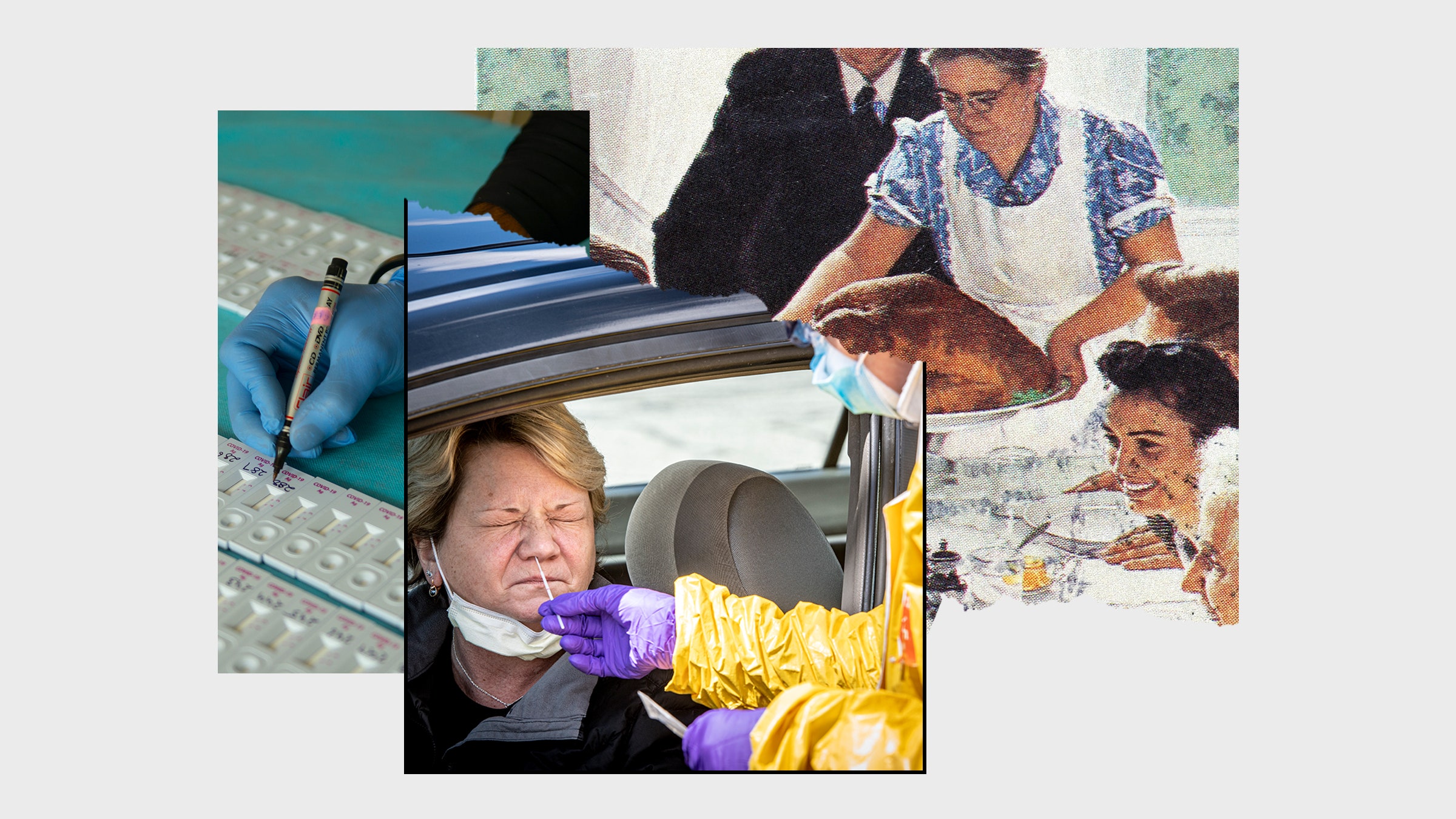

Photographs: J. Conrad Williams, Jr./Newsday/Getty Images; Pradeep Gaur/Getty Images; Norman Rockwell/Alamy

- 📩 Want the latest on tech, science, and more? Sign up for our newsletters!

- Schools (and children) need a fresh air fix

- What should you do about holiday gatherings and Covid-19?

- It’s time to talk about the virus and surfaces again

- The preexisting conditions of the coronavirus pandemic

- The science that spans #MeToo, memes, and Covid-19

- Read all of our coronavirus coverage here