The Advocate

Ukraine and the Europeans are vexed about how to deal with Trump. Gordon Sondland has a playbook.

Gordon Sondland recalls a time when he was in a car with Donald Trump. Sondland asked the then-U.S. president what he really thought of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

Gordon Sondland recalls a time when he was in a car with Donald Trump. Sondland asked the then-U.S. president what he really thought of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

“‘OK, Mr. President, cut the bullshit. What do you think of Kim?’” Sondland says he asked Trump. “And he goes, ‘That fucker would knife me in the stomach if he had the chance.’”

Sondland recounted this when I asked him what Trump’s Ukraine and Russia policy might look like if he won a second term as president. It’s the biggest question on everyone’s minds across Europe as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine drags into its third year. In classic Trump fashion, there’s no clear on-paper answer yet.

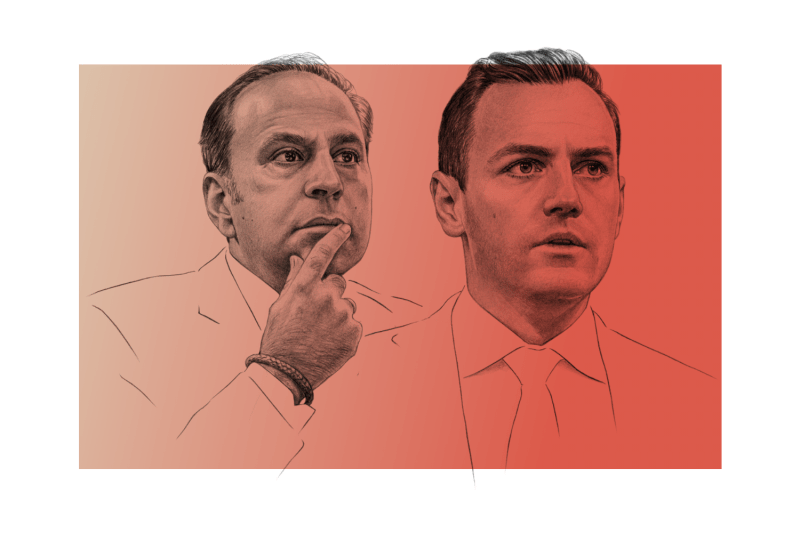

That’s why I wanted to pick Sondland’s brain. Sondland, a wealthy hotelier, served as Trump’s ambassador to the European Union from 2018 to 2020 and was thrust into the political maelstrom of Trump’s first impeachment scandal centered on Ukraine, even having to testify before Congress as a key witness in the impeachment inquiry. As such, Sondland saw firsthand the proverbial good, bad, and ugly of Trump’s foreign policy.

He’s also not shy about sharing his unvarnished opinions of his former boss. In his 2022 book he wrote about his time in government, The Envoy: Mastering the Art of Diplomacy With Trump and the World, Sondland said Trump was “kind of a dick” when he first met him and “a man with a fragile ego who wants more than anything to feed that ego the way an addict would feed a habit.” But he also wrote that Trump was “essentially right about many things, including how out of whack our relationship with Europe has become.”

Gordon Sondland, the U.S. ambassador to the European Union, arrives to testify in the impeachment inquiry against U.S. President Donald Trump on Capitol Hill in Washington on Nov. 20, 2019. Win McNamee/Getty Images

Sondland’s point about Trump’s comments on Kim was that Trump has a tendency to lavish praise on strongmen in public—be it the North Korean leader or Russian President Vladimir Putin—but in the end, the former president knows the stakes of the game and has a sober realpolitik approach to national security. “He does not like Putin at all. At all,” Sondland said. “And while he compliments Putin publicly, he does it because it’s a contrarian strategy.”

In short, Trump would be good for Ukraine, Sondland argues. Trump’s flippant talk of abandoning NATO allies that don’t spend enough money on defense or his public praise of Putin is just that—talk. And Trump’s unpredictability could play well into Ukraine’s hands, leaving Putin off kilter and guessing. “Madman theory wrapped in velvet gloves,” as Sondland put it.

It’s an interesting idea from one of Trump’s former diplomatic envoys, though it’s one that hardly anyone in Europe seems to be buying into. It’s also a theory Sondland is now working behind the scenes to enable should Trump be reelected. Because Sondland, a Seattle native born to Jewish parents who fled Germany to escape the Holocaust, is now a registered lobbyist for Ukraine. “Totally pro bono,” he said.

“As a [U.S.] citizen who believes strongly in Ukraine’s survival and total victory, I felt it’s my duty—given where the Republican Party is headed right now, some members of the Republican Party—to forcefully advocate with members of Congress and with others to support Ukraine,” he said.

Sondland stands for a portrait at the Four Seasons hotel in Washington on April 28, 2022. Carolyn Van Houten/The Washington Post via Getty Images

It’s hard from the outside to suss out details on what U.S. policy toward Europe and Russia would look like in a second Trump term, or even beyond it, and more urgently what that means for Ukraine. A six-month congressional delay in sending U.S. military supplies to Ukraine altered the momentum of the front lines and gave Russia a clear edge over the embattled Ukrainian military—a sign of how directly Ukraine’s fate in this war is linked to U.S. aid. That aid is now flowing freely again, but everyone, including Russia, is closely eyeing the upcoming U.S. elections and wondering whether, if Trump wins, that aid could be reduced or cut off.

Which is why I reached out to Sondland to understand more of how the foreign-policy circles around Trump view Ukraine and Russia. Sondland lives in Florida now, the proverbial mecca of the “Make America Great Again,” or MAGA, movement, and shuttles regularly to Washington to meet with Republican lawmakers. He has a foot in both Trump and non-Trump Republican foreign-policy circles; we met just before he traveled to Europe with former Vice President Mike Pence.

I met Sondland for breakfast last month at the Four Seasons in Washington, in a corner of the hotel’s brightly lit upscale restaurant surrounded by attentive waiters and well-to-do tourists. The Four Seasons is about as close as Sondland, a multimillionaire hotel magnate before his foray into diplomacy, could get to home turf in Washington.

Sondland shared his views with me over some overpriced black coffee, toast, and seasonal fruit, interspersing his takes on the world according to Trump, delivered in a booming voice, with quick smiles.

Evidence is displayed as Sondland testifies in the impeachment inquiry against Trump on Capitol Hill on Nov. 20, 2019. Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post via Getty Images

One of the big problems with Trump’s Russia policy is that it exists in a sort of twilight zone, even three years after he left office and with his next presidential campaign in full swing. In his first term, Trump cozied up to Putin at an infamous summit in Helsinki and elsewhere; was impeached by the House of Representatives on charges that he withheld aid to Ukraine to pressure it to dig up dirt on Joe Biden (he was acquitted by the Senate on a partisan-line vote); and repeatedly publicly bashed NATO. Yet his administration also ramped up sanctions on Russia; expanded the U.S. military footprint in Europe as well as funding programs for European deterrence; and withdrew from major arms control treaties that Moscow was, by all public evidence, blatantly cheating on.

On the 2024 campaign trail, Trump has suggested he would abandon NATO allies to a Russian invasion if they don’t meet NATO defense spending benchmarks, but he has also defended House Speaker Mike Johnson for pushing through the controversial national security funding package for Ukraine that nearly stretched the Republican-controlled House to its breaking point.

In short, Trump hasn’t spelled out what his second-term Russia policy would be. But Sondland’s views encapsulate one version of what it could look like: a hybrid of the “screw the Washington Blob, throw out the old playbook” MAGA instincts, with a side helping of bombshell social media posts that rock the political waters and dominate headlines—yet spliced together with the peace-through-strength style of Ronald Reagan’s hawkish foreign-policy platform. In Sondland’s view, this still boils down to Trump backing Ukraine to the hilt, even if he throws out public praises of Putin.

Sondland, as well as some (though not all) other former senior Trump national security officials still in the ex-president’s orbit, believes any Ukraine skepticism that Trump expresses publicly is empty rhetoric to cater to his hardcore base of supporters. “He supports Ukraine. He totally understands the stakes. I really believe that,” Sondland said. “But [Trump] is doing a head fake in order to keep his base solidly aligned until he gets through the election.”

If Trump is elected, he would “surge weapons” to Ukraine, perhaps to soften Russia up for negotiations, Sondland said. (Most Russia experts agree that any peace negotiation with Moscow at this point would only serve to give it time to reconstitute its battered forces to launch another phase of the war from a stronger hand later.)

Of course, for every Sondland out there touting this view, there are other former senior Trump officials arguing the opposite: Former Defense Secretary Mark Esper has warned that support for Ukraine would “crumble” if Trump were reelected, and former National Security Advisor John Bolton has said that Putin is “waiting” for Trump to win and that the Russian president expects Trump to abandon NATO and Ukraine.

Still, Sondland said that in his lobbying, he is targeting “fence-sitters” in the Republican Party, particularly in the House, who he thinks could be swayed to Ukraine’s cause after the dust of the congressional battle over the latest national security funding package dies down. He thinks there’s a faction of the MAGA wing of the party that can be convinced—though not all of it.

- Trump, then president, and Russian President Vladimir Putin arrive at a press conference in Helsinki on July 16, 2018. Yuri Kadobnov/AFP via Getty Images

- Trump walks with Polish President Andrzej Duda as he arrives at Trump Tower in New York City on April 17. Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

“When I say MAGA, there are people who support Trump, who like the term MAGA, Make America Great Again, that are thoughtful, intelligent, agree with President Trump’s general philosophy,” Sondland said. “And then there are people who just like to wear the red hat and really don’t know what they’re talking about. And I think you have to triage between those.”

Sondland then brought up an opinion I’ve heard repeatedly from former senior Trump officials in recent months: European leaders need to stop their nervous hand-wringing from afar and meet Trump face-to-face to make their case on Ukraine and NATO.

“I would encourage them to physically meet with Trump as much as possible because I think that, number one, he likes it. He likes the fealty. He likes the ring-kissing,” Sondland said. He paused and gave me a big grin here. “You know, if he were sitting here today listening to this conversation, I would say the same thing. And he would agree with it.”

He continued: “If you’re a European leader, if you’re an Ursula von der Leyen, if you’re a Klaus Iohannis, if you’re an Emmanuel Macron, you should be at Mar-a-Lago,” he said, referring to the presidents of the European Commission, Romania, and France, respectively. “And you should be talking about things you disagree on, and you should be helping move him in the right direction. Because he’s very easy to sell, because you know what he wants: Number one, he wants to be praised. And number two, he wants you to explain to him how this is in America’s interest.”

At least two senior European leaders have already done so: In April, British Foreign Secretary David Cameron met with Trump at Mar-a-Lago, where he reportedly tried to convince Trump to support additional U.S. aid to Ukraine, and Polish President Andrzej Duda met with him in New York (as the former president faced a slew of new criminal charges in New York courts), during which the two men discussed Duda’s proposal that NATO countries spend a minimum of 3 percent of their GDP on defense (an increase from the current 2 percent commitment), according to a readout of the meeting from the Trump campaign.

One leader who hasn’t yet come to kiss the ring is Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Sondland thinks that should change.

“I think Zelensky should be at Mar-a-Lago and not for a fancy dinner,” Sondland said. “I think he should show up there in his battle fatigues, and I think he should give Trump [a] very specific anecdotal example—simple, straightforward: ‘Mr. President, I’ve got a city here. It’s got 100,000 people in it, a lot of women and children. The Russians are this close. I need X, Y, and Z because it’s going to fall. Will you help me with this city? Will you tell your friends in Congress to get me X, Y, and Z to defend this city?’”

And if Trump asks “what’s in it” for the United States? Sondland outlines a compelling response from Zelensky tailor-made for the former president: “You may not like us, you may not care about us, but if we fall, you’re going to have a much more expensive mission on your hand, to pick up the pieces, because you can’t exist without Europe.”

Sondland addresses the media during a press conference at the U.S. Embassy in Bucharest, Romania, on Sept. 5, 2019. Daniel Mihailescu/AFP via Getty Images

Another factor is rattling Europeans’ nerves these days, however. And that’s the fact that Zelensky, entirely outside of his own control, was dragged into the noxious political cloud of Trump’s first impeachment scandal, which centered on a campaign by Trump and his allies to withhold U.S. military aid to Ukraine in a bid to pressure Zelensky’s government to dig up dirt on Biden ahead of the 2020 elections.

“He used that office for personal gain, and he used our foreign-policy assets, our national security assets … to try to get the Ukrainian president to do his personal and political bidding,” Marie Yovanovitch, the senior career diplomat who was U.S. ambassador to Ukraine at the time, later said. “I think the American people can expect better than that.”

Both Yovanovitch and Sondland testified publicly during the impeachment inquiry. Yovanovitch was fired before the impeachment saga first erupted on the national stage; Sondland was sacked immediately after the Senate acquitted Trump.

A week after Sondland testified before Congress, ProPublica and Portland Monthly published a joint report citing the accounts of three women who accused Sondland of making unwanted sexual contact with them in business settings before his time as an ambassador and of retaliating against them when they rejected his advances. Sondland vehemently denied the accusations, calling them “untrue” and saying he believed they were “coordinated for political purposes” in a statement at the time. His lawyer, Jim McDermott, said the accusations were meant to undermine Sondland’s credibility during the inquiry and could be considered “veiled witness tampering.” (Asked if he wished to comment for this story, Sondland pointed me to his lawyer’s previous statement.)

Newspaper headlines the day after Sondland testified before Congress in the impeachment inquiry, seen in New York on Nov. 21, 2019. Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images

From there, Sondland mostly faded back from the limelight before he released his book. He filed a lawsuit against former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and the U.S. government to recoup nearly $1.8 million in legal fees he incurred during the impeachment saga—fees that Pompeo reportedly assured him the government would pay. But otherwise, Sondland maintains ties to the Trump-dominated Republican political machinery that’s kicking into high gear for election season.

During Sondland’s book tour in 2022, he said he would not back Trump again due to his actions during the U.S. Capitol riots on Jan. 6, 2021, incited by the president’s repeated false claims of electoral fraud. “He really f—d that up,” Sondland told the Wall Street Journal of Trump that October. “I won’t support him.”

Today—after a Republican presidential primary cycle that saw Trump knock out his competitors one by one to become the presumptive nominee—Sondland has changed his tune and once again supports Trump.

As Sondland wrote in his book, Trump has notoriously thin skin and a penchant for emotionally lashing out at those who make him look bad. Could the stink of the first impeachment affect Trump’s views of Zelensky and Ukraine? I asked Sondland. He said he’s not worried about it—and gave a convincing answer even for sharp Trump critics.

“The thing about Trump is he’s a real paradox,” Sondland said. “He has a very thin skin, but he’s also very transactional. So he could be livid at you on Monday and say”—here Sondland pointed a finger at me—“‘Robbie, you’re dead to me. You really pissed me off. Get out of here. You’re fired,’ whatever. And on Wednesday, you call him up and say, ‘Mr. President, I have something that might be of interest to you.’ He’ll go, ‘Tell me more.’” Meaning, if Trump thinks defending Ukraine is a good deal, all that impeachment baggage would be water under the bridge.

And what about the ramifications of all of Trump’s social media posts casting doubt on whether the United States will back NATO allies? “Show business,” Sondland said.

Show business it may be, but such statements today could have far bigger implications than they did before now that there’s a major land war in Europe, to say nothing of Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling. An off-the-cuff comment or tweet about not defending NATO allies in 2018 didn’t carry quite the same weight that it would in 2024 or beyond, when U.S. signaling and deterrence measures could be the one thing that heads off a Russian attack on NATO soil.

But Sondland is unbothered. “Well, we’re not pulling out [of NATO],” he said. “And Trump knows that. But he likes to destabilize. Because you know what? It takes destabilization in order to get action.”

He continued: “Otherwise, everyone likes to talk, everyone likes to clink glasses, have photo ops, eat the canapes, and then go home, and nothing fucking happens. The minute you start really destabilizing, saying things like he said, telling people you’re going to pull out, telling people, ‘You’re on your own if you don’t do your part,’ all of a sudden it gets people moving. It’s back to the madman theory.”

This all paints a neat picture of good news for Ukraine if Trump wins a second term. Given the chaos of the first Trump administration, it seems suspiciously too neat.

So I pressed Sondland: You painted a picture of Trump as a master strategist playing a careful game of geopolitical chess wrapped in the madman theory. Don’t you think that’s too rosy a picture? Are you not just retroactively dressing up an incredibly impulsive president who fired off new policies from the hip and left allies (and his own government) often scrambling to respond?

Here, Sondland fell back on one of his maxims about Trump and the difference between talk and action.

“It’s very simple,” Sondland replied, adopting his brief first-person role as Trump. “‘I got a base I got to keep happy. The base loves this shit. This is what I’m going to do to keep the base happy. Once I’m governing, I understand what the big-picture issues are. I’m not governing right now—I’m just talking.’”

Whether that’s enough to reassure Ukraine, Sondland’s new client, is another matter entirely.

Robbie Gramer is a diplomacy and national security reporter at Foreign Policy. Twitter: @RobbieGramer

More from Foreign Policy

The Man Who Tried to Save Israel From Itself

This time, Israel must heed Theodor Meron’s warning.

‘Somalia on Steroids’: Sudan Conflict Escalates

The U.S. special envoy for Sudan warns that the geopolitical fallout from the spiraling civil war could be immense.

Biden’s Foreign-Policy Problem Is Incompetence

The U.S. military’s collapsed pier in Gaza is symbolic of a much bigger issue.

Why Is Xi Not Fixing China’s Economy?

Explanations from insiders range from ignorance to ideology.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber? .

Subscribe Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.