BBC/Summer Films/Aodh Breathnach

BBC/Summer Films/Aodh Breathnach'After you've been stabbed, you feel quite emasculated'

Filmmaker Aodh Breathnach, who survived a stabbing, explores why there's a stigma around men talking. "I had to really try hard not to cry," he says.

This article contains graphic content.

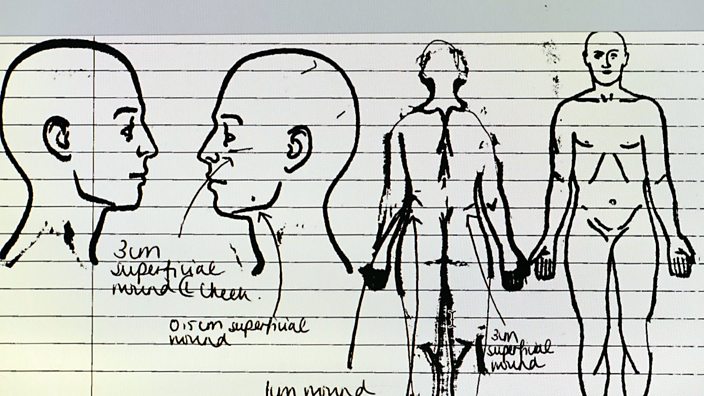

“It was unlike anything I'd ever heard before, [the sound of] the blade going in and out of my head,” says Aodh Breathnach, who was stabbed in 2015.

When he was 26, the filmmaker got into a disagreement after a night out in Bristol.

Aodh was stabbed five times during the altercation, twice in his head.

“I was angry,” Aodh remembers. “I think toxic masculinity is a phrase that can be overused but it probably applies in this case. Pride led me to risk-taking behaviour and essentially led me to have a fight with someone who had a blade.”

“I went to hospital, I was stapled, glued, stitched up,” he adds. “I was very lucky to come away without any life-changing injuries.”

He was home the next morning, went back to work three days later and never pressed charges.

BBC/Summer Films/Aodh Breathnach

BBC/Summer Films/Aodh BreathnachFor years, Aodh didn’t speak about being stabbed or the impact it had on him.

But now he is exploring how survivors cope after being stabbed and the importance of mental health support in the BBC documentary Scars: Surviving a Stabbing.

And, unlike in his case, Aodh recognises that many young people caught up in knife crime lose their lives. Statistics show there were more than 50,000 offences - including 234 homicides - involving a knife or sharp instrument in England and Wales in the year ending March 2023.

‘Mental health impacts of violence are profound’

In the months after being stabbed, Aodh had panic attacks and night terrors.

“I found myself not feeling safe in my own home, not feeling safe around town,” he says.

While Aodh’s physical wounds healed in a few weeks, the psychological impact of his stabbing took a serious toll.

“I had to really try hard not to cry and to hold back my emotions," he remembers. “I suppose I tried to hide it as much as possible.”

BBC/Summer Films/Aodh Breathnach

BBC/Summer Films/Aodh BreathnachSince speaking to other survivors, Aodh thinks there are a few reasons people don’t talk about being stabbed, including the risk of further threat.

“Someone has stuck a knife into your body and you know it could happen again,” he explains.

“Men also struggle to speak about their feelings and show vulnerability. After you've been stabbed, you feel quite vulnerable, quite emasculated.”

Consultant clinical psychologist Dr Tosin Bowen-Wright, who has worked with youth offenders and stabbing victims including Aodh in the documentary, adds that while talking helps those who have experienced trauma, stigma is often a barrier that stops people opening up.

This, she says, is made worse by the fact that accessing mental health services is a "challenge".

Simon Dowe, from the charity Redthread which works with St Giles Trust and runs a youth violence intervention programme, says the impact of violence on mental health is "profound", adding that without greater understanding of the topic and more support "the fear and isolation children and young people feel will continue, and so will the violence".

‘Healing is not an easy thing to do’

After his attack, Aodh didn’t seek out help for his mental health. Now, eight years on, he’s exploring the options available to him, like talking therapy and restorative justice.

Aodh also spoke to other survivors to understand how they were coping.

He met Kieran Quinlan, who was stabbed in the heart while being robbed. Kieran was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after his attack and it took him four years to speak publicly about his experience.

BBC/Summer Films/Aodh Breathnach

BBC/Summer Films/Aodh Breathnach“The thing I was most scared of was being judged,” Kieran says, adding that he’d often wear high-necked T-shirts to hide his scar.

He threw himself into fitness while he recovered and now runs a gym in Birmingham.

“It weren't easy but it got better every time I spoke about it,” Kieran says, adding that exercise and restorative justice helped improve his confidence after the attack.

But Aodh is quick to note that “healing is not an easy thing to do - it can be a really painful process”.

While exploring mental health support, Aodh was introduced to the concept of restorative justice, which he describes as “a therapeutic approach when victims of crimes connect with perpetrators, with the intention of both parties finding closure and it being mutually beneficial”.

BBC/Summer Films/Aodh Breathnach

BBC/Summer Films/Aodh BreathnachFor weeks, he weighed up whether to reach out to his perpetrator, noting that the outcome is often unpredictable. As with any therapy, it should be approached with the help of a professional, he says.

In Aodh's view, psychological and emotional support can be "really essential" tools in helping those affected by stabbings, by making them less susceptible to mental health problems and making them less likely to harm others.

Sources of support are available via the BBC Action Line.

You can watch Aodh’s full journey in Scars: Surviving A Stabbing on BBC iPlayer now.

Originally published 17 October 2023.