Exposed

The true story of a lost documentary.

Secretly filmed inside the IRA, it then vanished.

The Discovery

A countdown plays from 10 to one, then a grainy picture comes into focus.

A young woman with striking red hair is being instructed in how to prime a bomb.

“Your det [detonator] is the last thing to connect,” says the bombmaker.

A glowing light indicates the bomb is live and ready to go.

“Now you know what your target is and you know what to do.”

What we’re seeing has been hidden from view for almost 50 years.

A film that captured striking images of IRA members making bombs and carrying out gun attacks, often unmasked.

These are the opening images of a film that got closer to the Irish Republican Army than any other documentary made across decades of conflict in Northern Ireland.

We’re an audience of BBC producers, journalists and editors, and we’ve seen hundreds, maybe thousands, of hours of archive footage. But nothing like this.

That’s because almost as soon as this extraordinary film was made, it essentially vanished.

And from the moment we saw those scenes – and who was in them – we’ve been unpacking the strange story of The Secret Army, the unusual way it was made in 1972 and its unexplained disappearance.

The BBC’s part of the story started almost six years ago, when a source handed a researcher a box with some old video tapes.

He’s told he might find something interesting in them.

We’re in the middle of making a series about the history of the Troubles and new, original archive is just about number one on our wish list.

Two tapes in the box look interesting, they’re marked part one and part two but they are in an old format which is decades out of date.

Somewhere in the BBC‘s vaults a machine is found to duplicate them.

As we sit and watch, the opening sequence ends with a huge bomb explosion in a street that looks familiar but we can’t yet identify.

Then comes the film’s title – The Secret Army.

Is this real?

The American-made film is truly remarkable.

IRA leaders, all wanted men, are on screen speaking openly and frankly about their campaign in 1972.

But it’s the footage of rank-and-file IRA personnel taking part in shootings and bombing operations which is most surprising.

Over the years the IRA laid on “photo ops” but the scenes were strictly controlled with the IRA participants almost always masked.

In The Secret Army we are able to watch as the IRA members – with little or no efforts at concealment - wage their war.

But could these extraordinary scenes have been staged?

Maybe these were more sophisticated “photo ops” with actors playing IRA parts.

All of us agree that one scene stands out.

The unmistakable figure of Martin McGuinness, then the most prominent IRA leader in Londonderry, is shown helping prepare what seems to be a car bomb in one of the city’s back streets.

In the film you see a cluster of men packing what looks like explosives into a Volkswagen estate car.

The faces of the men are not all clear to be seen, but McGuinness is instantly recognisable by his stooped shoulders and gait.

The car is driven away and the camera team appears to follow it.

The next scene captures the moment a car bomb explodes in the city centre.

It’s a huge blast on Shipquay Street in the commercial heart of Derry.

Buildings all along the street are wrecked.

This is clearly not a staged explosion on a movie set.

No one was killed but we would later learn that at least 26 people were injured.

But is it the same “car bomb” we saw earlier in the back streets?

Could the filmmakers have spliced a staged assembly of the bomb with the real explosion of another bomb?

There was one important clue: we had seen the car registration plate before it was driven away – 7337 UI.

We dig into newspapers from the time, and into the BBC’s own archive.

First we get a date for the bomb - 21 March 1972.

The bomb was reported to have been inside a Volkswagen.

Then we spot something in a newspaper photo.

A number plate.

It’s misshapen and badly damaged but the registration is still obvious.

And it matches – 7337 UI.

This is incendiary footage.

Here is Martin McGuinness, the man who would later lead the IRA to peace, who would eventually meet and greet Queen Elizabeth II, helping to make a car bomb.

Why does it seem that no one has ever seen it?

How, and why, did this film apparently disappear?

We’ve spent years trying to answer those questions.

In doing so, we’ve pieced together a remarkable story which tells much about the IRA in the early days of the Troubles, long before anyone could imagine the conflict would run over three decades and leave so much death and destruction in its wake.

1972

Not long before St Patrick’s Day 1972, Jacob Stern got off a plane at Dublin airport and jumped into a car driven by J Bowyer Bell, a producer and writer of The Secret Army.

J Bowyer Bell

J Bowyer Bell

Bowyer Bell, an academic and author who had worked at Harvard and other prestigious universities, was well acquainted with Ireland, having spent years living there in the 1960s while he researched a history of the IRA.

Jacob Stern though was setting foot in Ireland for the first time.

A composer, he had flown from New York to work on The Secret Army, but on the drive to Dublin city centre he found himself immediately immersed in the strange world of the Troubles.

“Bow had said to me: ‘If you look out the back window, you’ll see that tannish automobile behind us, and it’s Irish Special Branch.’

"And behind that car, there was another automobile, and Bow said:

`That’s British MI6.’

Jacob Stern, Composer

Jacob Stern, Composer

“And we pulled up in front of this sandwich shop, and I thought we were to go in and get a sandwich, but no, no, we walked in the front door, and straight through the shop out the back door, and there was a car waiting for us there, and we got in it and drove out a different street.”

Bowyer Bell himself was no naïve academic.

“I associate with gunmen,” he once told an interviewer.

By 1972 he’d travelled to, and written about, just about every conflict zone on the planet.

He was always alert for watchers. In the febrile atmosphere of that period, there was even a rumour that a Bulgarian hit team was hunting down the film crew.

It was a tumultuous time in Northern Ireland.

The conflict which had begun in 1969 had spiralled into near civil war.

A couple of years on, killings were now routine.

There were IRA gun and bomb attacks every day.

Bowyer Bell’s team was filming just weeks after Bloody Sunday, when the Army shot dead 13 unarmed Catholic civilians after a civil rights march in Derry.

A fourteenth would die later.

Thirteen people were killed and 15 wounded on Bloody Sunday

Thirteen people were killed and 15 wounded on Bloody Sunday

It had brought worldwide attention to the conflict but more significantly it brought a huge wave of recruits to the IRA.

The secret army they wanted to film had never appeared stronger.

And the IRA’s reach was felt beyond the confines of Northern Ireland.

Across the border, in Dublin, the British Embassy had been attacked by angry crowds before it was set alight and burned down by IRA members.

As sentiment flowed in support of the IRA’s armed campaign it wasn’t just the British authorities who feared them, so too did the Irish government, everyone mindful that the IRA had already declared that 1972 would be their “Year of Victory”.

Unmasked

The film crew passed through the frontier between the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland using fake press credentials and began to film with the IRA.

Martin McGuinness, then just 21 years old, is among the first they film.

He’s driving around Free Derry with guns, showing bullets to children, giving the crew a taste of life inside the network of barricades which kept the security forces and the police out.

His front seat passenger supplied a running commentary like a professional tour guide.

His name was Tony Devine.

Devine stills lives in Derry. Now a grandfather six times over, his IRA days which saw him shot at and jailed are long behind him.

“We were only teenagers,” Devine told us.

“We weren’t used to talking to film crews, and they asked Martin would he drive around and show them the area, and explain stuff to them?

"And Martin says: 'I’ll only do it if you go with me.'

“And I says: 'All right.’

“I think Martin actually asked me to do the talking, now that I think about it. Martin said: ‘You, you do the talking.’”

The IRA members were taking an enormous risk - one that hadn’t been taken before or since – allowing themselves to be filmed with weapons, without disguising their identities.

That’s because the IRA’s very existence depended on secrecy, at least to the extent that they could hide and move unnoticed within the civilian population.

Yet members of the IRA Army Council, its seven most senior leaders, sat on camera and talked about what they did.

Even the Chief of Staff – Seán Mac Stíofáin – who risked arrest on both sides of the border – sat and talked about his daily routine.

J Bowyer Bell and Seán MacStíofáin (right)

J Bowyer Bell and Seán MacStíofáin (right)

“You wouldn’t know what Bowyer Bell told them,” said Tim Pat Coogan, an eminent historian of the IRA and a rival author.

“Did they think there was going to be a Hollywood bonanza from this film that money would flow into the coffers?

“He probably promised them all sorts of good publicity, and a film that was going to make them all famous worldwide.”

The IRA did attempt to control the risks they were running.

“For very good reasons, the IRA was afraid the British might decide to confiscate our film,” one crew member recalled.

“And if it happened to us we might just be providing their enemy with enough faces to lift the entire IRA rank and file.”

The car bomb scene in Derry is an example of the type of footage that would have been giving the security forces useful intelligence.

Most of the half a dozen IRA members are ultimately identifiable.

Jacob Stern watched the bomb being put together.

He then joined the crew at the top of Shipquay Street, right in the heart of Derry, to see it explode.

A bomb warning had been given but he knew enough to be concerned.

“Not all bombs go off as they’re supposed to. So, I was in a heightened state of alert and worried,” Stern said.

At least 26 people were injured by the bomb, none seriously, but there was no sense of that in The Secret Army.

It did show the wrecked businesses up and down the street but it didn’t show the human casualties.

IRA Control

Before they left the city, the crew filmed other IRA operations including a prolonged gun battle on the edge of Free Derry.

The gunmen are unmasked and appear utterly oblivious of the camera. It suggests a carefree attitude to the organisation’s own security.

Yet we learned the IRA was very serious about minimising some risks attached to the project.

One of the crew recalled a conversation between McGuinness and an IRA member who was responsible for getting the team and their undeveloped footage out of Northern Ireland.

McGuinness is reported to have said: “You know if you don’t get that film across the border I’ll have to shoot you myself.”

The film did get across the border, but the IRA’s concern about keeping its contents secure didn’t stop there.

They had made a secret deal with the filmmakers giving them control over what would be said and who would be shown in the final film.

In New York we found legal papers that spelled out the arrangement.

The IRA had sought and obtained an agreement with Bowyer Bell for “control and rights of censorship”.

Bowyer Bell’s lawyer wrote that because the IRA leaders had been “cooperative and permitted the film to be made they could not be denied these rights,” nor could Bowyer Bell “permit these men to be compromised”.

Jacob Stern had first alerted us to this arrangement and outlined how the IRA intended to enforce it.

Jacob Stern at his home in Arizona

Jacob Stern at his home in Arizona

“They said, if any separate parts of the film were attempted to be taken separately to America, that we would be all shot at the airport. Just like that: ‘We’re gonna kill ya.’”

The film’s raw footage was never to leave Ireland.

Only the finished film could leave.

Stern explained that was why he had been brought to Ireland.

The IRA had insisted everything, including the music and the sound mix, was done before the film left the island.

So the composer, who normally would do his work in a New York studio, had flown across the Atlantic.

The IRA laid on more filming in Belfast.

Another gun battle is captured in the west of the city.

And another bomb is filmed from start to finish.

Again, many of those filmed are easily identifiable.

“The film is propaganda, but it’s also a remarkable film,” said Diarmaid Ferriter, professor of Modern Irish History at University College Dublin.

“The intimacy of the footage is really striking. There’s nothing else like that, that I’m aware of and to see what is being depicted in that film in 1972 in particular is quite remarkable, because of the level of access that’s there when it comes to senior IRA figures, but also the personal testimony of women in particular, which again is highly unusual in the context of republican paramilitarism and the history of the IRA.”

The red-haired woman featured throughout: patrolling with a rifle in her hand, driving a scout car for other bombers, taking notes at a meeting of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade - but also cooking dinner and actually going to school.

She turned out to be 17-year-old Geraldine Hughes. She died in 2006.

Geraldine Hughes

Geraldine Hughes

But her appearances throughout the film teach us to continue to be careful with what we’re seeing.

In that opening bomb sequence, the handbag containing the bomb changes shape before the bomb is planted.

The filmmakers were sometimes prepared to create a narrative that didn’t adhere to the truth.

The camera rolled south of the border too.

The film features a bomb-making class. The students mostly keep their backs to the camera, but the instructor is shown full face.

It took a bit of digging but we discover his identity.

His name was Paddy Ryan.

Extraordinarily he was then a member of the IRA’s Army Council.

And here he is, on camera, in his own Dublin home, taking IRA recruits carefully through the dos and don’ts of priming a bomb.

It is a truly remarkable scene in an already astonishing film.

Lost

We learned there were at least two private screenings of the film in Dublin before it was shipped back to America.

First, the IRA leadership saw it and signed it off.

Then a bunch of the IRA personnel who took part got to see it.

One person, now dead, even took their parents along. They all loved it.

It wasn’t hard to see why.

The film portrayed the IRA as deeply religious people – the camera followed one Army Council member to church – but also as thoroughly modern: the young, especially young women, are featured throughout it.

Des Long, as shown in the film

Des Long, as shown in the film

But Tony Devine never saw the final film. Nor did another IRA participant Des Long.

Both wondered what had happened to what they viewed as an IRA propaganda effort.

Tony Devine

Tony Devine

J Bowyer Bell died in 2003 but one of his children, Becky Waring, recalls the sense of anticipation around the possible broadcast of the documentary on the CBS network.

She says: “I remember us all being very excited. Dad is going to do a movie.”

In the last week of June the most popular news show in America, Walter Cronkite’s CBS Evening News, ran some clips from the film - the bomb-making class and the Derry car bomb sequence.

This may have given the team confidence that CBS would screen the entire documentary.

Then several weeks later, after it had arrived back in the US, the film was shown in a New York pub.

A journalist from the Irish Times was there too and he wrote a generally positive review.

But the headline said much: “Not-so-secret army filmed.”

If the various intelligence agencies and the British, Irish and US governments did not know about The Secret Army before the CBS News report and the Irish Times review they surely knew about it now.

And this is the moment the film essentially disappears from public view.

Becky Waring told us her dad arranged for a special screening at her school but the family had hoped it would make a much bigger splash.

She says: “We kept waiting for it to be on TV but it never was. It was a big disappointment.”

There were some private screenings over the years afterwards. It once showed at a film festival in Rome. But that was it.

The composer Jacob Stern tried to call in a favour with a neighbour who was a network TV executive.

“I took it to his house and handed it to him. The next day he gave it back to me and said: ‘It's too romantic. It doesn't seem real.’

“And you know, I was upset about that because by this time I was emotionally involved in the success of it.”

In spite of its extraordinary scenes, the film proved very difficult to sell.

Possibly because attitudes in America towards the IRA were shifting.

What Americans might have considered the IRA’s historic struggle for Irish freedom was no longer seen through the sole prism of Bloody Sunday.

Just as the big sales push began that July, IRA bombs ripped through Belfast and then the tiny village of Claudy, killing a total of 18 people and injuring many dozens more.

The IRA was blamed for bombing Claudy but the paramilitary group never admitted to it

The IRA was blamed for bombing Claudy but the paramilitary group never admitted to it

Could the film’s failure to sell be explained exclusively by evolving attitudes to the IRA?

A lifelong friend of Bowyer Bell offers an alternative explanation.

Roberto Mitrotti pictured with Bowyer Bell

Roberto Mitrotti pictured with Bowyer Bell

Roberto Mitrotti says that the academic blamed the long hand of Britain.

He said Bowyer Bell told him: “The British government was too afraid of the repercussions that the film could have with the Irish community in the US which was a very powerful, wealthy community.

"So the British government decided to clamp down on it and put pressure on the US government to stop the film.”

Bombshell

In fact it seems that despite the IRA’s efforts at secrecy British intelligence knew all about the film from pretty early on.

Zwy Aldouby (left)

Zwy Aldouby (left)

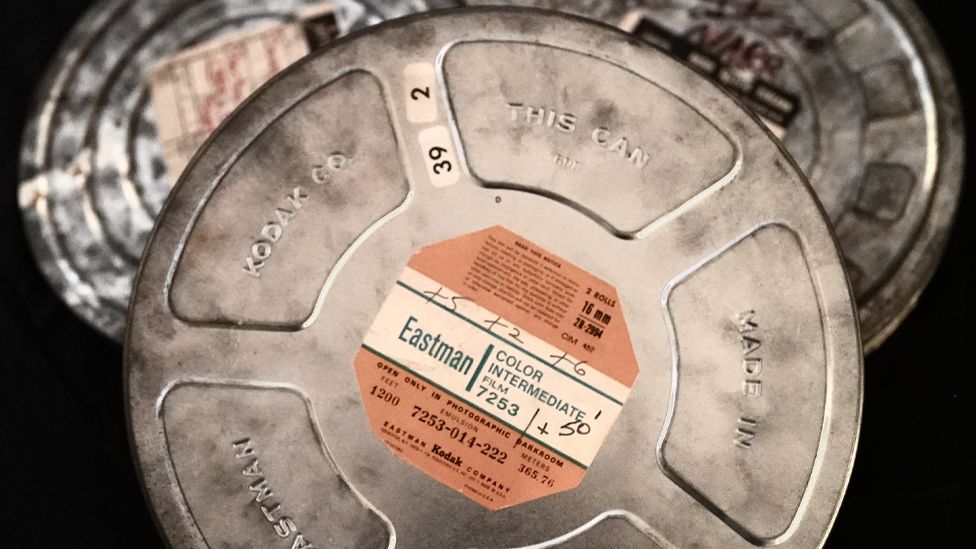

Executive Producer Leon Gildin said that Bowyer Bell and the film’s director, Zwy Aldouby, told him that British intelligence had seen every frame of it before it was completed.

Gildin explained that all the unedited 16mm colour footage had to go to London for processing because there were no facilities in Dublin at the time.

He said this is when British intelligence had intervened.

“I have to assume that the producers of the film had no alternative but to turn the material over to British intelligence if British intelligence said we want to see it.

“I don’t think that it was a betrayal of any confidence or anything like that. I just think had they developed it in Dublin perhaps no-one would have seen it. But by virtue of it being developed in London that’s where British intelligence got their hooks into it.”

Could this be true?

We asked MI5 and MI6 about this, and other matters related to the film, and they both declined to make any comment.

But we do manage to corroborate one important part of Leon Gildin’s account.

We find the original film reels stacked along with hundreds of paintings in a back room in a New York apartment.

It’s Bowyer Bell’s former home. His daughter explains that when Bell wasn’t writing or reading he was painting.

Written on the reels we spot the address of the Dublin house the film was made in. And the London address of a TV and film processing centre - evidence that the footage had gone across the Irish Sea.

And if Gildin is right - it means that British intelligence would have been able to see every scene, including footage the IRA censors would have cut from the final film.

And there were other possible routes the intelligence agencies may have used to exploit the film for their ends.

In our research we discovered that Bowyer Bell and the director Zwy Aldouby both had connections to spies.

Spies?

We knew a little about J Bowyer Bell already.

He was an expert on terrorism and wrote at least 20 books over his lifetime.

His best known book was a history of the IRA - also called The Secret Army.

First published in 1970 it is still regarded as an excellent work.

He was trusted by most Irish republicans, but over the many years that he visited and worked in Ireland, there were rumours that he was somehow tied to American intelligence - that he was CIA.

He dismissed these rumours as laughable.

We found ourselves in a silenced library at Harvard University, sifting through the papers of a former professor there, Samuel P Huntington.

He was a lifelong friend of Bell, a consultant for the US State Department, and once served on the US government’s National Security Council.

We were looking for correspondence between Bell and Huntington and we found it.

More importantly we discovered that Bell had sent his CV to Huntington.

And there, in black and white, confirmation that from 1974, at least, Bell was working as a consultant for the CIA and other US government agencies.

And then another detail, spelling out the one-time status of his security clearance with the CIA : TS – which we learned stands for Top Secret.

It’s intriguing.

Zwy Aldouby

Zwy Aldouby

And just as intriguing is the backstory of his main collaborator on the film - the director Zwy Aldouby.

He’s a journalist and author with no background in documentaries that we can find. But he does have a background with Israeli Intelligence and with Nazi hunting.

The CIA and FBI have files on him, going back to 1961 when Aldouby plotted to kidnap a former Nazi who was hiding out in Spain and bring him to justice.

A source reports to the CIA that earlier Aldouby was part of team of Nazi hunters based in Vienna run by Israeli intelligence.

His own son Ilan tells us he believes his father was an intelligence operative in the 1950s. But why would Israel have any interest in the IRA?

Ilan Aldouby has a theory that makes some sense. He suggests that Israeli intelligence would have been interested in the IRA at the time because of their emerging links to Libya’s Col Gaddafi.

“So, my father, if he worked with or collaborated with the Mossad or Israeli intelligence, it would be a clear fit.”

Mossad denied he was a member when we asked them.

J Bowyer Bell’s daughter Becky Waring says it is inconceivable that her dad would have been a CIA officer or informant.

She confirmed that he consulted for the CIA - but said that he was just advising on theories related to war and terrorism.

“It’s on his resume because that was one of the ways he made money.

“He wrote proposals to the CIA saying: ‘I can teach a course in your class about, you know, terrorism.’

“And he was open about it. But that is a completely different thing from being a spy. And he was never that. I mean, he probably wouldn’t have told me if he was. But I just can’t even imagine it.”

Friends of Bowyer Bell agreed. He might have advised the CIA on theories of terrorism but he would not have betrayed those he worked with in the IRA.

Jacob Stern describes his friend as “straight forward, honest, extremely, extremely brilliant”.

Tony Devine and Des Long

Tony Devine and Des Long

Former IRA men Tony Devine and Des Long are not convinced.

They’re now all but certain that Bowyer Bell and Aldouby were working to the agenda of intelligence agencies.

Devine said: “Knowing what I know now, never in a million years, they shouldn't have been allowed to film what they filmed.”

Conclusion

It’s impossible to be definitive about the making of this film. The CIA declined to answer almost all our questions but told us they had no role in the making of the documentary.

But evidence of intelligence agencies involvement in it, unbeknownst to the IRA, is compelling.

Bowyer Bell may have been more than a consultant to the CIA.

But it’s also possible he too was manipulated along with everyone else, by the spymasters.

What we do know is that the commercial failure left Bowyer Bell and Aldouby in debt.

Both had borrowed money to make it.

And we know that the IRA had opened up their secret army at huge risk for no reward.

We showed the film to journalist and author Ed Moloney, among the foremost experts on the IRA.

Moloney had never seen it before.

He wondered what had possessed the IRA to make it at all.

“Had they lost their minds?

"I mean to take such a huge risk with so many important people all incriminating themselves in one way or another, creating hostages to fortune and goodness knows what sort of damage that could be done to the IRA.

“What had happened to their heads?

“Of course every single one of them would be vulnerable to pressure from the authorities.

"And we don’t know if the British found out about this film, what they did with it.

Martin McGuinness (right) at the funeral of IRA member Colm Keenan in March 1972.

Martin McGuinness (right) at the funeral of IRA member Colm Keenan in March 1972.

“Did they use it to recruit, not just Martin McGuinness, but other people who were in the film to become agents? That’s going to be one of the great unanswered questions of the Troubles I think.”

None of the IRA participants that we’ve spoken to say the material was used against them.

One source from the world of spooks told us: “Intelligence agencies hoover up any and all material. It is not for arresting purposes.

"The information goes into a drawer.

"Some drawers are never opened again. Some are.”

A legal expert suggested it would have been difficult to prosecute unless one of the filmmakers would also testify.

Historian Bob White, one of the very few to have seen the film before we found it again, said one IRA member told him that if arrested they were to say they were just acting.

Dáithí Ó Conaill being interviewed by Bowyer Bell

Dáithí Ó Conaill being interviewed by Bowyer Bell

One startling fact: Days after filming concluded, an IRA delegation was flown to London for secret talks with the British Government.

The names of the IRA delegation are now well known: Chief of Staff Seán MacStiofáin, Dáithí Ó Conaill, Seamus Twomey, Martin McGuinness, Ivor Bell and Gerry Adams, who had to be released from internment to attend.

Bell and Adams were the only members of the IRA delegation who had not been filmed, and, according to the filmmakers, watched by their enemy.

The Secret Army is on BBC iPlayer - and on BBC Two Northern Ireland on 27 March at 21:00 and BBC Four on 2 April at 22:00.

Credits:

Written by:

Darragh MacIntyre and Chris Thornton

Film Producer / Director:

John O'Kane

Film Executive Producers:

Chris Thornton

Gwyneth Jones

Additional Images:

Derry Journal

Pacemaker Press

Press Association

Production Photographs:

David Gifford

Online Production:

Peter Hamill

Online Assistant Editor:

Judith Cummings