Queen Elizabeth II leaves complex legacy for Aboriginal Australians

- Published

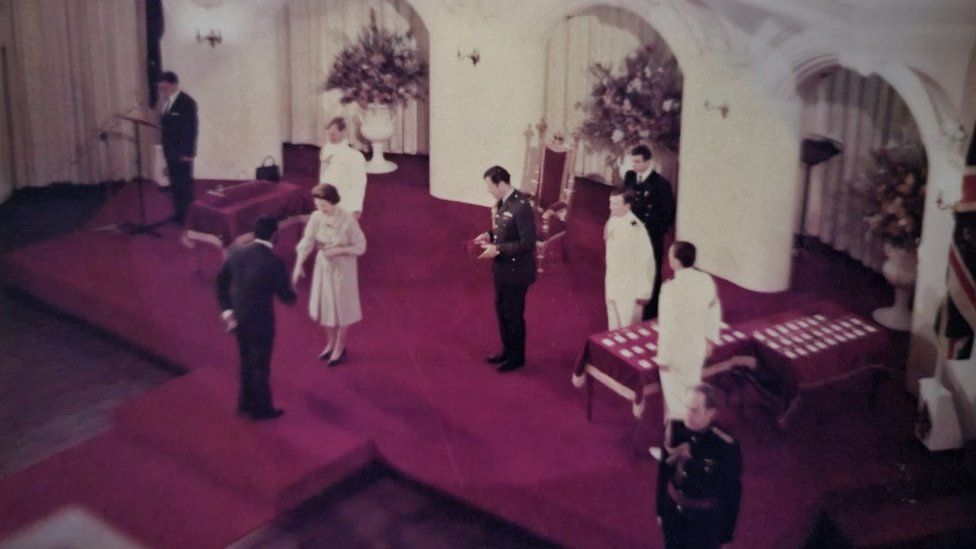

Proudly displayed in Narelda Jacobs' childhood home in Australia was a photo of her father, Cedric, meeting Queen Elizabeth II.

"As a kid, I grew up looking at her in an aspirational way and thinking: 'Gosh, that's the Queen! And that's my dad receiving an [MBE] order from the Queen!'" the Aboriginal Australian television presenter says.

"She's someone that I always looked up to."

But as Ms Jacobs grew older, the meaning of the photo shifted.

When she looks at it now, she sees a sovereign standing in front of a man who dedicated his life to having the sovereignty of his own people recognised.

"And he died waiting for that recognition," the Whadjuk Noongar woman tells the BBC.

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have spoken of complicated emotions after the Queen's death.

The oldest continuing cultures on Earth, they suffered greatly from colonialism. The arrival of Captain James Cook in 1770 set off events that dispossessed Indigenous Australians of their land. Massacres, profound cultural disruption, and intergenerational trauma followed.

When Queen Elizabeth II first visited Australia in 1954, First Nations people were not counted as part of the population, and children were still being forcibly removed from their families to be assimilated into white households. In some parts of her tour, Aboriginal Australians were actively hidden from view.

Much has changed since, but Indigenous Australians remain disproportionately worse off in terms of health, education and other measures compared to non-Indigenous Australians.

"We're still not doing as well… and that's because of colonial rule," Wiradjuri academic Sandy O'Sullivan says.

Mixed feelings

As a result Australia has struggled with the question of how to celebrate her life while acknowledging some of the country's darkest chapters.

A decision to lower the Aboriginal flag to half-mast in her honour - in line with other official flags - drew some criticism, as did the decision to suspend parliament for a fortnight. A promise to rename a Melbourne hospital from an Aboriginal word, Maroondah, to Queen Elizabeth II Hospital has been attacked as "tone deaf".

Controversially, the Australian Football League Women's decided against mandating a minute's silence for the Queen last week because it was Indigenous Round. But the National Rugby League fined and suspended an Indigenous player after she wrote an offensive post about the Queen that some defended as freedom of speech.

For University of Canberra Chancellor and Aboriginal elder Tom Calma, the Queen led a life of service "with a whole lot of dignity and humanity".

"She inherited, at a very young age, a whole lot of global challenges. We've seen a lot of change and she's been at the helm of that," says Prof Calma, a Kungarakan and Iwaidja man.

She seemed sympathetic, he says, to the desires of First Nations people - such as in 2000 when she called for the government to "ensure prosperity touches all Australians", pointing out many Indigenous people felt "left behind".

But some say the Queen's legacy in Australia is impossible to separate from the invasion and colonisation of the country.

Among them is Greens Senator Lidia Thorpe, who referred to the Queen as a coloniser while taking her oath in parliament earlier this year.

Watch: Indigenous Australian senator calls the Queen a "coloniser"

Indigenous people never ceded their sovereignty, the Djabwurrung Gunnai Gunditjmara woman wrote in the Guardian Australia last week.

"The institutions that British colonisation brought here, from the education that erases us to the prisons that kill us, are designed to destroy the oldest living culture in the world," wrote Ms Thorpe.

"That's the legacy of the Crown in this country."

For others, there is criticism of what the Queen herself didn't do. Many Indigenous Australians made appeals to her for greater support during her reign.

Among them was Ms Jacobs' father, an Anglican reverend and one-time National Aboriginal Conference chair. Though he was always "very fond" of the Queen, Cedric Jacobs had spoken to her about his people's desire for a treaty.

"Could there have been something that she could have done?" Ms Jacobs asks.

Prof O'Sullivan says: "I don't have a lot of time for people who want to celebrate the idea of somebody passing away."

But it's not fair to paint the Queen as simply a "kindly grandmother" given she was so influential and had "enormous wealth", the academic adds.

She used that power to be an "incredibly eloquent" advocate for some causes, Prof O'Sullivan says. "[But] she certainly didn't do anything to make our lives better."

Prof Calma argues the Queen inherited colonial tensions she had no part in creating.

"There's always an argument that more could have happened, but that's not always in the hands of the monarch," he says.

"We can't continually blame the Crown, when we've had our own constitution since 1901. It is the Australian government who has to step up."

'An opportunity'

Some argue an Australia that recognises the harm colonisation has done to First Nations people, cannot remain subject to a British monarch.

But a referendum on a republic looks at least three years away. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has committed to first holding a referendum on recognising Indigenous people in Australia's constitution and giving them a Voice to Parliament - a new advisory body.

And even if Australia becomes a republic it may not leave the Commonwealth, Prof Calma says.

Some urge the monarchy to embrace a new era.

"This is an opportunity for a clean slate," Prof O'Sullivan says. "I have a lot of a lot of hope."

Some Indigenous Australians want King Charles III to make an apology for the damage done by colonialism - like that offered to New Zealand's Māori in 1995.

There are also calls for reparations - financial compensation, the return of land and artefacts, and the repatriation of ancestral remains located in British museums.

The King could also consider lending his support to the campaign for the Voice to Parliament, some say.

All the BBC spoke to said they wanted the King to meet with First Nations people, and to listen.

"It is really frustrating. These are the same conversations that our leaders would have had with his mum," Ms Jacobs said.

"But I don't want anybody else to die waiting to have their sovereignty as a First Nations person recognised."

- Published12 September 2022

- Published15 September 2022

- Published13 September 2022

- Published18 September 2022

- Published9 September 2022