|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

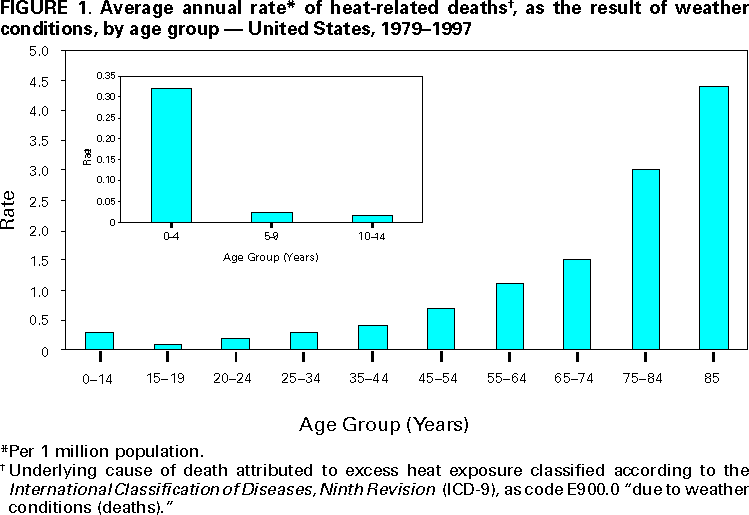

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Heat-Related Illnesses, Deaths, and Risk Factors --- Cincinnati and Dayton, Ohio, 1999, and United States, 1979--1997During the summer of 1999, a heat wave* occurred in the midwestern and eastern United States. This period of hot and humid weather persisted from July 12 through August 1, 1999, and caused or contributed to 22 deaths among persons residing in Cincinnati (18 deaths) and Dayton (four deaths). A CDC survey of 24 U.S. metropolitan areas indicated that Ohio recorded some of the highest rates for heat-related deaths during the 1999 heat wave, with Cincinnati reporting 21 per million and Dayton reporting seven per million (CDC, unpublished data, 1999). This report describes four heat-related deaths representative of those that occurred in Cincinnati or Dayton during the 1999 heat wave, summarizes heat-related deaths in the United States during 1979--1997, describes risk factors associated with heat-related illness and death, and recommends preventive measures. Case ReportsCase 1. In July 1999, a 34-year-old woman with schizophrenia was found dead in a group home in Cincinnati at 9 a.m. A caretaker discovered the decedent lying on the couch of a second-floor living room; two windows were open and fans were blowing. The decedent was last seen alive around noon the previous day. She had a medical history of hypertensive heart disease, asthma, and swelling of the ankles for which she had been taking a diuretic, furosemide. The temperature inside the home at the time of her death was unknown; however, the ambient temperature was 92.1 F (33.4 C) when the decedent was found. Her liver core temperature was 106.2 F (41.2 C). The Hamilton County Coroner's Office attributed the death to heatstroke. Case 2. In July 1999, an 84-year-old man was found dead in his Dayton residence. He lived alone and was found lying in bed, supine and nude. The doors to his home were locked and all the windows were shut. When the body was discovered, the temperature inside the home was approximately 86 F (30 C). A fan was blowing air toward the ceiling, an air conditioner was present but not running, and the thermostat was set in the heat mode. The temperature in Dayton that day reached >90 F (>32 C) with high humidity. An autopsy report indicated the decedent suffered from arteriosclerosis and hypertensive cardiovascular disease. The Montgomery County Coroner's Office attributed the death to exposure to excessive environmental heat. Case 3. In July 1999, a 65-year-old man was found in his residence by a neighbor, unresponsive and having seizures. Following transport to the emergency department of a local hospital by the Cincinnati Fire Division, the patient had a rectal temperature of 108 F (42.2 C) and subsequently died. The decedent had a history of chronic alcoholism and hypertensive cardiovascular disease. He lived alone in an attic apartment without air conditioning. The Hamilton County Coroner's Office attributed the death to hypoxic encephalopathy following resuscitation for heatstroke. Case 4. In August 1999, a 24-year-old man was found lying face down on the living room floor of his Dayton apartment in an early stage of decomposition. The room temperature was 99 F (37.2 C), and the apartment had no air conditioning. The decedent lived alone and was last seen alive 3 days earlier at his home by a neighbor. The decedent had a history of mental illness and depression and had been taking benztropine. The Montgomery County Coroner's report listed the probable cause of death as cardiac arrhythmia caused by hyperthermia resulting from exposure to high environmental temperature. United StatesDuring 1979--1997, the most recent years for which data are available, an annual average of 371 deaths in the United States (1) were attributable to "excessive heat exposure"† (median: 249; range: 148 in 1979 to 1700 in 1980) (5). This translates into a mean annual death rate of 1.5 per million and a median annual death rate of one per million. Because of a record heat wave, the heat-related death rate for 1980 was more than three times higher than that for any other year during the 19-year period. The median annual death rate for hyperthermia in persons aged >65 years was three per million. During 1979--1997, 7046 deaths were attributable to excessive heat exposure: 3010 (43%) were "due to weather conditions," 351 (5%) to heat "of manmade origin," and 3683 (52%) "of unspecified origin." Of the 2954 persons whose deaths were caused by weather conditions and for whom age data were available, persons aged >65 years accounted for 1783 (44%) deaths, and persons aged <14 years accounted for 127 (4%) deaths. Except children aged <14 years, the average annual rate of heat-related deaths increased with each age group, particularly for persons aged >65 years (Figure 1). During 1979--1997, among persons of all ages, the annual death rate "due to weather conditions" was two times higher for men (0.8 per million) than for women (0.4 per million), and more than three times higher for blacks (1.6 per million) than for whites (0.5 per million). Arizona and Missouri (four per million) and Arkansas and Kansas (three per million) had the highest annual age-adjusted rates for heat-related deaths "due to weather conditions" (1). Reported by: MP Adcock, PhD, City of Cincinnati. WH Bines, MS, Montgomery County; FW Smith, MD, State Epidemiologist, Ohio Dept of Health. Health Studies Br, Div of Environmental Hazards and Health Effects, National Center for Environmental Health; and an EIS Officer, CDC. Editorial Note:Behavioral and environmental precautions are essential to preventing illness and death§ associated with heat waves or sustained periods of hot weather (daytime heat index¶ of >105 F [>40.6 C] and a nighttime minimum temperature of 80 F [26.7 C] persisting for at least 48 hours) (6). Illnesses associated with high environmental temperatures include heatstroke (hyperthermia), heat exhaustion, heat syncope, and heat cramps (2). Heatstroke is a medical emergency characterized by the rapid onset and increase (within minutes) of combined elements (e.g., heat and humidity) on the body. the core body temperature to >105 F (>40.6 C), lethargy, disorientation, delirium, and coma (2). Heatstroke is often fatal despite rapidly lowering the body temperature (e.g., ice baths), because frequently irreparable neurologic damage has occurred (2). Heat exhaustion is characterized by dizziness, weakness, or fatigue often following several days of sustained exposure to hot temperatures, and results from dehydration or electrolyte imbalance (2); treatment includes replacing fluids and electrolytes and may require hospitalization (2). Physical exertion during hot weather increases the likelihood of heat syncope and heat cramps caused by peripheral vasodilation (2). Persons who lose consciousness because of heat syncope should be placed in a recumbent position with feet elevated and given fluid and electrolyte replacement (2). For heat cramps, physical exertion should be discontinued and fluids and electrolytes replaced (2,7). All persons are at risk for hyperthermia when exposed to a sustained period of excessive heat (2); however, factors that increase the risk for hyperthermia and heat-related death include age (e.g., the elderly), chronic health conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease or respiratory diseases), mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia), social circumstances (e.g., living alone), and other conditions that might interfere with the ability to care for oneself (2,3). Other risk factors are alcohol consumption, which may cause dehydration, previous heatstroke, physical exertion in exceptionally hot environments, the use of medications that interfere with the body's heat regulatory system, such as neuroleptics (e.g., antipsychotics and major tranquilizers), and medications with anticholinergic effects (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, some antiparkinsonian agents, and some over-the-counter sleep medication [2--4]). Persons working in hot indoor or outdoor environments should take 10--14 days to acclimate to high temperatures. Although adequate salt intake is important, salt tablets are not recommended and can be hazardous to some persons (2). Although the use of fans may increase comfort at temperatures <90 F (<32.2 C), fans are not protective against heatstroke when temperatures reach >90 F (>32.2 C) and humidity exceeds 35% (2,4). Measures for preventing heat-related illness and death during a heat wave include spending time in air conditioned environments, increasing nonalcoholic fluid intake, exercising only during cooler parts of the day, and taking cool baths (2). Elderly persons should be encouraged to take advantage of air conditioned environments (e.g., shopping malls, senior centers, and public libraries), even for part of the day (2--4). Public health information about exceptionally high temperatures should be directed toward persons aged >65 years and <5 years. Parents should be educated about the heat sensitivity of children aged <5 years (2), and should never leave them unattended, especially in motor vehicles. When a heat wave is predicted, friends, relatives, neighbors, and caretakers should check frequently on elderly, disabled, mentally ill, chronically ill, and home-bound persons, and during periods of high temperatures, prevention messages should be disseminated to the public as early and often as possible. References

*Three or more consecutive days of air temperatures >90 F (>32.2 C). †The National Association of Medical Examiners' (NAME) definition for heat-related death includes exposure to high ambient temperature either causing the death or as substantially contributing to it, cases where the body temperature at time of collapse was >105 F (>40.6 C), and a history of exposure to high ambient temperature and the reasonable exclusion of other causes of hyperthermia (1). Because death rates from other causes (e.g., cardiovascular and respiratory disease) increase during heat waves (2--4) (defined by the National Weather Service as >3 consecutive days of temperature >90 F [>32.2 C]), deaths classified as caused by hyperthermia represent only a portion of heat-related death. § Underlying cause of death attributed to "excessive heat exposure," classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), code E900.0, "due to weather conditions" (deaths); code E900.1, "of manmade origin" (deaths); or code E900.9, "of unspecified origin" (deaths). Data were obtained from the Compressed Mortality File of CDC's National Center for Health Statistics, which contains information from death certificates filed in 50 states and the District of Columbia. All rates were age-standardized to the 1990 U.S. population. ¶ Heat index is a measure of the effect of combined elements (e.g., heat and humidity) on the body. Figure 1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 6/5/2000 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|