Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Alcohol Use Among Pregnant and Nonpregnant Women of Childbearing Age --- United States, 1991--2005

Alcohol consumption during pregnancy is a risk factor for poor birth outcomes, including fetal alcohol syndrome, birth defects, and low birth weight (1). In the United States, the prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome is estimated at 0.5--2.0 cases per 1,000 births, but other fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs)* are believed to occur approximately three times as often as fetal alcohol syndrome (2). The 2005 U.S. Surgeon General's advisory on alcohol use in pregnancy, advises women who are pregnant or considering becoming pregnant to abstain from using alcohol (2). Binge drinking is particularly harmful to fetal brain development (2,3). Healthy People 2010 objectives include increasing the percentage of pregnant women who report abstinence from alcohol use to 95% and increasing the percentage who report abstinence from binge drinking to 100% (4). To examine the prevalence of any alcohol use and binge drinking among pregnant women and nonpregnant women of childbearing age in the United States and to characterize the women with these alcohol use behaviors, CDC analyzed 1991--2005 data from Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveys. The findings indicated that the prevalence of any alcohol use and binge drinking among pregnant and nonpregnant women of childbearing age did not change substantially from 1991 to 2005. During 2001--2005, the highest percentages of pregnant women reporting any alcohol use were aged 35--44 years (17.7%), college graduates (14.4%), employed (13.7%), and unmarried (13.4%). Health-care providers should ask women of childbearing age about alcohol use routinely, inform them of the risks from drinking alcohol while pregnant, and advise them not to drink alcohol while pregnant or if they might become pregnant (2,5).

BRFSS conducts state-based, random-digit--dialed telephone surveys of the noninstitutionalized U.S. civilian population aged ≥18 years, collecting data on health conditions and health risk behaviors. For this report, CDC analyzed BRFSS data from 1991 to 2005 from all 50 states and the District of Columbia for women aged 18--44 years. The median response rate among states, based on Council of American Survey and Research Organizations (CASRO) guidelines, ranged from 71.4% in 1993 to 51.1% in 2005. This report focuses on two drinking behaviors: any use, defined as having at least one drink of any alcoholic beverage in the past 30 days, and binge drinking, defined as having five or more drinks on at least one occasion in the past 30 days.† The wording of the question regarding any alcohol use was changed in 1993, 2001, and 2005,§ the wording of the question regarding binge drinking was changed in 1993 and 2001.¶ BRFSS questionnaires are available at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/questionnaires.htm.

Percentage estimates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated each year for the two drinking behaviors among pregnant and nonpregnant women. Logistic regression was used to examine the association of age, race/ethnicity, education, employment, and marital status with the two drinking behaviors for pregnant and nonpregnant women with the behaviors as the dependent variables and sociodemographic characteristics as the independent variables in the models. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) were calculated to describe significant differences by characteristic category. Data from 2001--2005 were aggregated to provide stable estimates to assess the association of these characteristics with the drinking behaviors. Data were weighted to state population estimates and aggregated to represent a nationwide estimate.

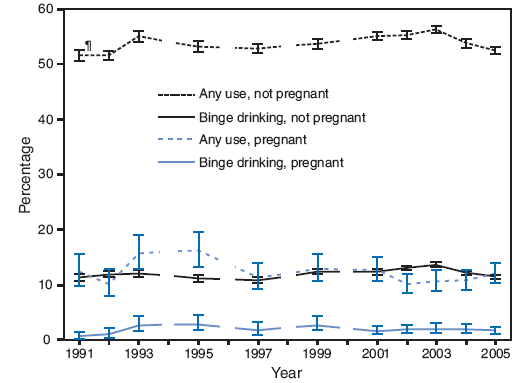

Of the 533,506 women aged 18--44 years surveyed during 1991--2005, 22,027 (4.1%) reported being pregnant at the time of the interview. The prevalence of any alcohol use and binge drinking among pregnant and nonpregnant women from 1991 to 2005 did not change substantially over time (Figure). The average annual percentage of any alcohol use among pregnant women was 12.2% (range: 10.2%--16.2%), of binge drinking among pregnant women was 1.9% (range: 0.7%--2.9%), of any alcohol use among nonpregnant women was 53.7% (range: 51.6%--56.3%), and of binge drinking among nonpregnant women was 12.1% (range: 10.8%--13.7%).

Of the 329,975 women aged 18--44 years surveyed during 2001--2005, 13,820 (4.2%) reported being pregnant at the time of the interview. Among pregnant women, 17.7% of those aged 35--44 years reported any alcohol use, compared with 8.6% of pregnant women aged 18--24 years (AOR = 2.3). Greater percentages of pregnant women with at least some college education (11.2%), or a college degree or more (14.4%), reported alcohol use than pregnant women with a high school diploma or less (8.5%) (AORs = 1.4 and 1.9, respectively). A greater percentage of employed pregnant women (13.7%) reported alcohol use than unemployed pregnant women (8.3%, AOR = 1.5), and a greater percentage of unmarried pregnant women (13.4%) reported alcohol use than married pregnant women (10.2%, AOR = 2.2) (Table). In addition, a greater percentage of employed pregnant women (2.3%) reported binge drinking, compared with unemployed pregnant women (1.3%, AOR = 1.8), and a greater percentage of unmarried pregnant women (3.6%) reported binge drinking than married pregnant women (1.1%, AOR = 4.4).

Reported by: CH Denny, PhD, J Tsai, MD, RL Floyd, DSN, PP Green, MSPH, Div of Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC.

Editorial Note:

A 2002 report using 1991--1999 BRFSS data determined that, from 1995 to 1999, the percentage of pregnant women reporting any alcohol use decreased, whereas the prevalence of binge drinking during pregnancy and the prevalence of both drinking behaviors among nonpregnant women did not change (6). This report expands on the 2002 report, examining data collected during 1991--2005; this broader perspective indicates that alcohol use and binge drinking among pregnant women and nonpregnant women of childbearing age did not change substantially over time. The prevalence of both types of drinking behavior among pregnant women remain greater than the Healthy People 2010 targets, and greater progress will be needed to reach them (4,6).

Alcohol use levels before pregnancy are a strong predictor of alcohol use during pregnancy (7). A proportion of women who use alcohol continue that use during the early weeks of gestation because they do not realize they are pregnant. Approximately 40% of women realize they are pregnant at 4 weeks of gestation, a critical period for fetal organ development (e.g., central nervous system, heart, and eyes) (7). Because approximately half of all births are unplanned, clinicians should screen and advise women of childbearing age of the potential consequences of using alcohol during pregnancy (2).

The findings that, among pregnant women, those who were older, more educated, employed, and unmarried were more likely to use alcohol support results from previous studies, but the reasons for these patterns are not well understood (6,8). Further research is needed; however, some possible reasons include that 1) older women might be more likely to be alcohol dependent and have more difficulty abstaining from alcohol while pregnant, 2) more educated women and employed women might have more discretionary money for the purchase of alcohol, and 3) unmarried women might attend more social occasions where alcohol is served.

The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, BRFSS data are self-reported and subject to recall and social desirability biases; underreporting of negative health behaviors such as binge drinking and any alcohol use while pregnant is likely. Second, BRFSS survey questions have changed over time, which can affect prevalence estimates. Third, declining response rates, likely attributable in large part to changes in telephone technology (e.g., increases in caller identification and dedicated fax and computer lines) and greater reluctance among the public to respond to telephone surveys, might affect prevalence estimates. Fourth, BRFSS excludes households without landline telephones, including households with only cellular telephones; therefore, the results might not be representative of certain segments of the U.S. population. Finally, this report likely underestimates the current prevalence of binge drinking because it used the 2005 definition (five or more drinks on at least one occasion) rather than the current definition for women of four or more drinks on at least one occasion.

Alcohol use during pregnancy continues to be an important public health concern. Effective screening and counseling are available for women of childbearing age in the preconception and prenatal periods (9). CDC's efforts to reduce the prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy include funding Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Regional Training Centers to improve health-care provider skills at screening women for alcohol use and providing brief interventions (10). CDC also is engaged in ongoing work with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the Indian Health Service to train health-care workers in systems of care funded by these agencies (i.e., alcohol and drug treatment programs and women's health clinics in American Indian communities) (9). Finally, seven CDC-funded state-based fetal alcohol syndrome prevention programs for women in high-risk geographic areas or high-risk subpopulations are completing work in developing, implementing, and evaluating population-based and targeted programs. These programs will provide valuable insights for CDC's continuing efforts to reduce the prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy.

Acknowledgment

This report is based, in part, on data contributed by BRFSS state coordinators and contributions by O Devine, PhD, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC.

References

- Bailey BA, Sokol RJ. Pregnancy and alcohol use: evidence and recommendations for prenatal care. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2008;51:436--44.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. US Surgeon General releases advisory on alcohol use in pregnancy. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. Available at http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/pressreleases/sg02222005.html.

- Maier SE, West JR. Drinking patterns and alcohol-related birth defects. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:168--74.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010 midcourse review [objectives 16-17a, 16-17b]. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. Available at http://www.healthypeople.gov/data/midcourse.

- US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. Dietary guidelines for Americans 2005. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. Available at http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/document/default.htm.

- CDC. Alcohol use among women of childbearing age---United States, 1991--1999. MMWR 2002;51:273--6.

- Floyd RL, Decoufle P, Hungerford DW. Alcohol use prior to pregnancy recognition. Am J Prev Med 1999;17:101--7.

- Haynes G, Dunnagan T, Christopher S. Determinants of alcohol use in pregnant women at risk for alcohol consumption. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2003;25:659--66.

- Floyd RL, Sobell M, Velasquez MM, et al; Project CHOICES Efficacy Study Group. Preventing alcohol-exposed pregnancies: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:1--10.

- FASD Regional Training Centers Consortium. Educating health professionals about fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Am J Health Educ 2007;386:364--73.

* FASD is an umbrella term that includes fetal alcohol syndrome (a lifelong condition that causes physical and mental disabilities, characterized by abnormal facial features, growth deficiencies, and central nervous system problems) and other harmful effects on persons whose mothers use alcohol during pregnancy. These effects include physical, mental, behavioral, or learning disabilities with possible lifelong implications. The term FASD is not intended for use as a clinical diagnosis.

† Beginning in 2006, the definition of binge drinking by women changed to four drinks on at least one occasion. Because of this change, data collected after 2005 are not included.

§ Any alcohol use: "Have you had any beer, wine, wine coolers, cocktails, or liquor during the past month, that is, since (date from one month before interview)" (1991--1992). "During the past month, have you had at least one drink of any alcoholic beverage such as beer, wine, wine coolers, or liquor? (1993--2000). "A drink of alcohol is one can or bottle of beer, one glass of wine, one can or bottle of wine cooler, one cocktail, or one shot of liquor. During the past 30 days, how often have you had at least one drink of any alcoholic beverage?" (2001--2004). "During the past 30 days, have you had at least one drink of any alcoholic beverage such as beer, wine, a malt beverage or liquor?" (2005).

¶ Binge drinking: "Considering all types of alcoholic beverages, that is beer, wine, wine coolers, cocktails, and liquor, as drinks, how many times during the past month did you have five or more drinks on an occasion?" (1991--1992). "Considering all types of alcoholic beverages, how many times during the past month did you have five or more drinks on an occasion?" (1993--2000). "Considering all types of alcoholic beverages, how many times during the past 30 days did you have five or more drinks on an occasion?" (2001--2005).

FIGURE. Percentage of women aged 18--44 years who reported any alcohol use or binge drinking,* by pregnancy status --- Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveys, United States,† 1991--2005§

* Defined as five or more drinks on at least one occasion.

† BRFSS survey data were not available for 1994, 1996, 1998, and 2000. Data also were not available from Kansas, Nevada, and Wyoming for 1991; from Arkansas and Wyoming for 1992; from Rhode Island for 1993 and 1994; from the District of Columbia for 1995; and from Hawaii for 2004.

§ Beginning in 2006, the definition of binge drinking by women changed to four drinks on at least one occasion. Because of this change, data collected after 2005 are not included.

¶ 95% confidence interval.

Alternative Text: The figure above shows the percentage of women aged 18-44 years who reported any alcohol use or binge drinking, by pregnancy status from 1991 to 2005. Of the 533,506 women aged 18-44 years surveyed during 1991-2005, 22,027 (4.1%) reported being pregnant at the time of the interview. The prevalence of any alcohol use and binge drinking among pregnant and nonpregnant women from 1991 to 2005 did not change substantially over time.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services. |

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Date last reviewed: 5/21/2009